BANK TREASURERS BEWARE THE IDES OF MARCH

Listen to an audio version of this newsletter on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Amazon Music, Audible, or your favorite podcast platform.

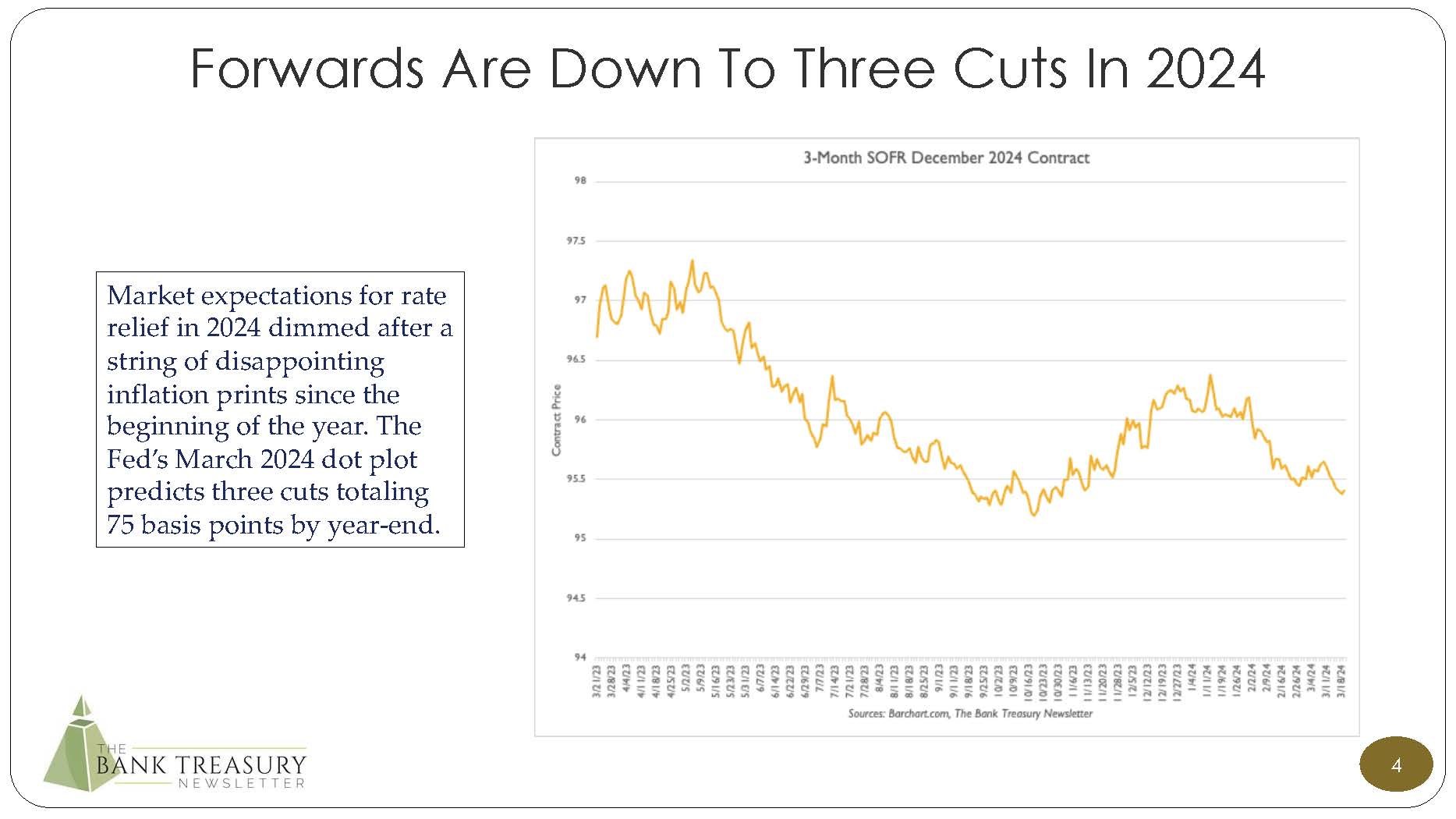

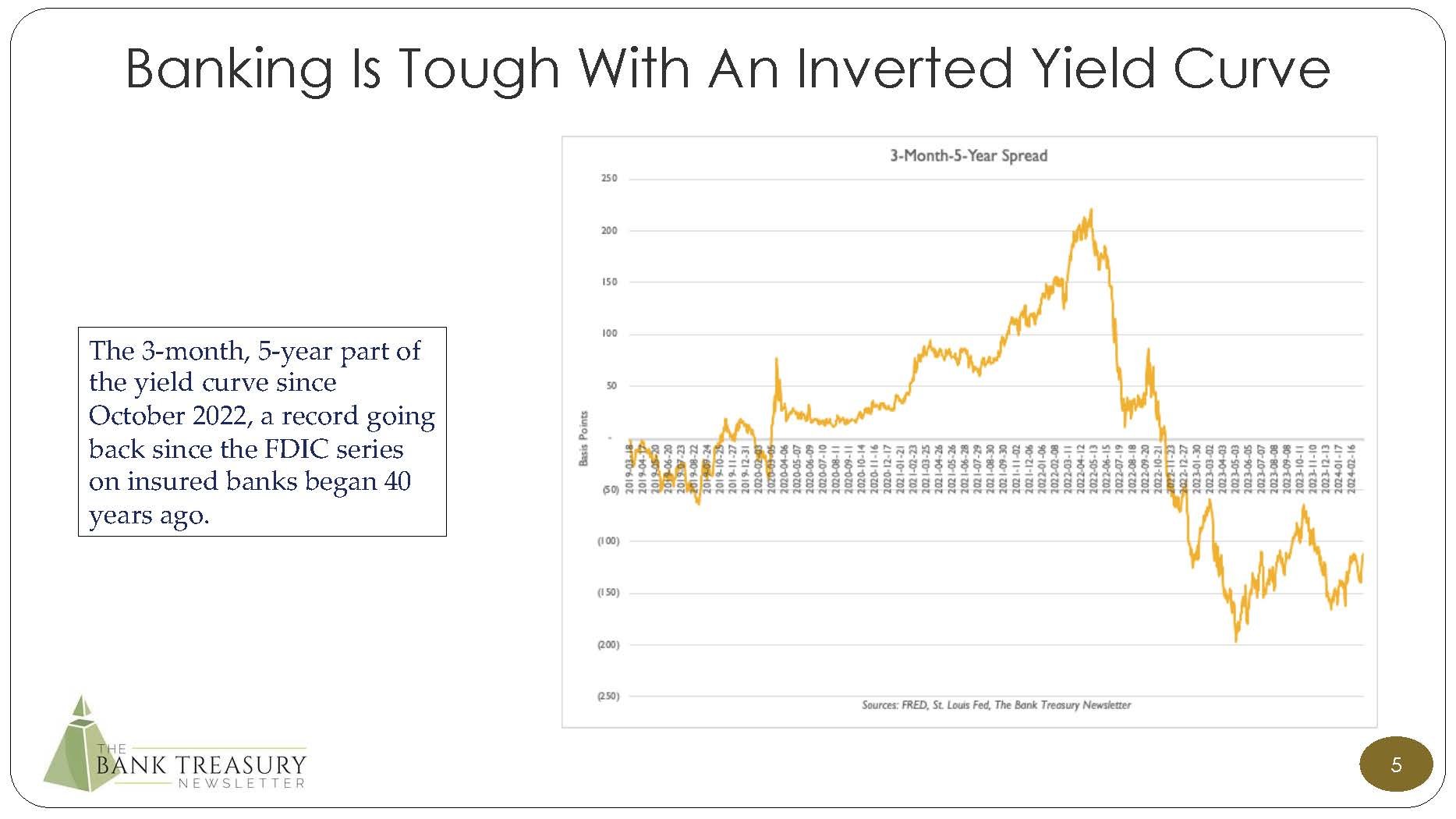

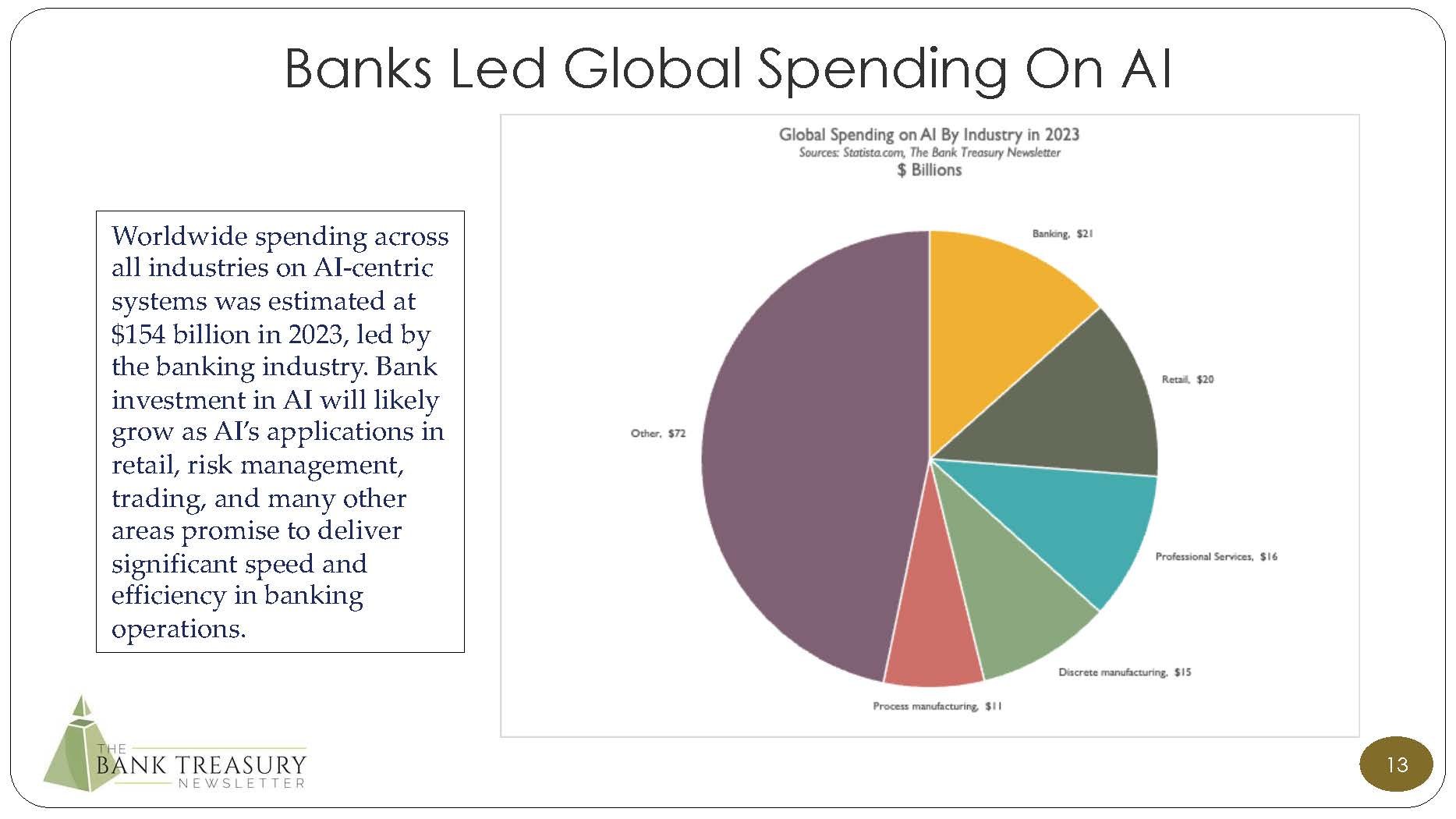

The Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) did not lower the target range for the Fed Funds rate at its meeting this month. Though it remains predisposed to begin rate cuts this year, requiring only that the data move "sustainably toward 2 percent," the recent string of disappointing monthly inflation data suggests that the road to the first interest rate cut remains uncertain and longer than the market had previously expected based on earlier encouraging comments from Fed officials. Notably, forward rates now predict three cuts this year, beginning probably by July 2024, compared to the six it predicted last January. It is finally aligned with the Fed's latest dot plot. But even three cuts this year run against a very tight calendar as this fall's Presidential election season begins. Unless inflation data starts to show some consistent movement in the right direction very soon, three rate cuts may begin to look more like two, maybe one, or maybe no rate cuts at all this year.

The 10-year Treasury rallied in Q4 2023, which improved the fair value of available-for-sale (AFS) portfolios, but it still ended the year with more than 10 points underwater. Since then, the yield on the 10-year increased to 4.4%, about 100 basis points higher than where it stood last year when Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) announced that it would restructure virtually its entire underwater AFS portfolio. The timing of the announcement could not have been worse; it was the day Silvergate Bank announced that it would close, which triggered a massive run on the bank that caused it to fail. But the option to sell bonds from AFS even at a loss remains a crucial asset-liability management (ALM) tool that bank treasurers have used before and even since SVB's failure, as their restructuring of their AFS portfolios in Q4 2023 demonstrates. They have publicly stated their intent to take advantage of market opportunities to do more.

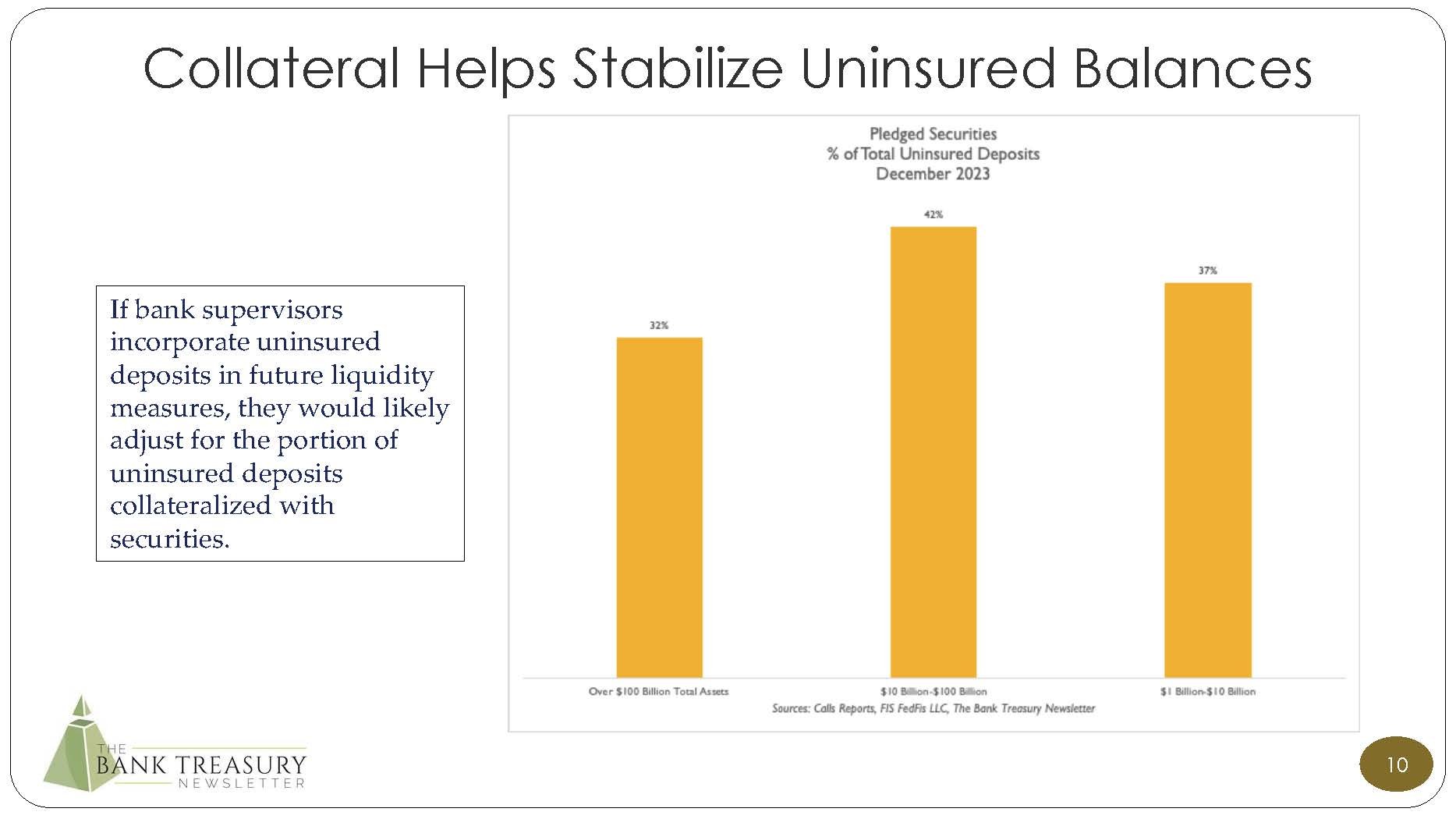

Bank management continues to remain optimistic that adverse trends in deposits are stabilizing as their books close on Q1 2024. However, the level of noninterest-bearing deposits has fallen from 30% of total deposits in March 2022 to 23% in Q4 2023, the lowest since the onset of Covid. Bank treasurers are skeptical that depositors will shift back so quickly to noninterest-bearing deposits after the Fed begins to cut rates. They believe they will continue to hold a lower level of noninterest-bearing deposits than they held before the Fed began raising rates two years ago. Uninsured deposit balances fell from 45% of total deposits at year-end 2022 to 39% at the end of March 2023, where they have held stable now through the end of the year. Some banks have observed uninsured depositors shifting away from collateralized deposits because of their cost, a sure sign that their anxiety level after last year's bank crisis is practically back to normal.

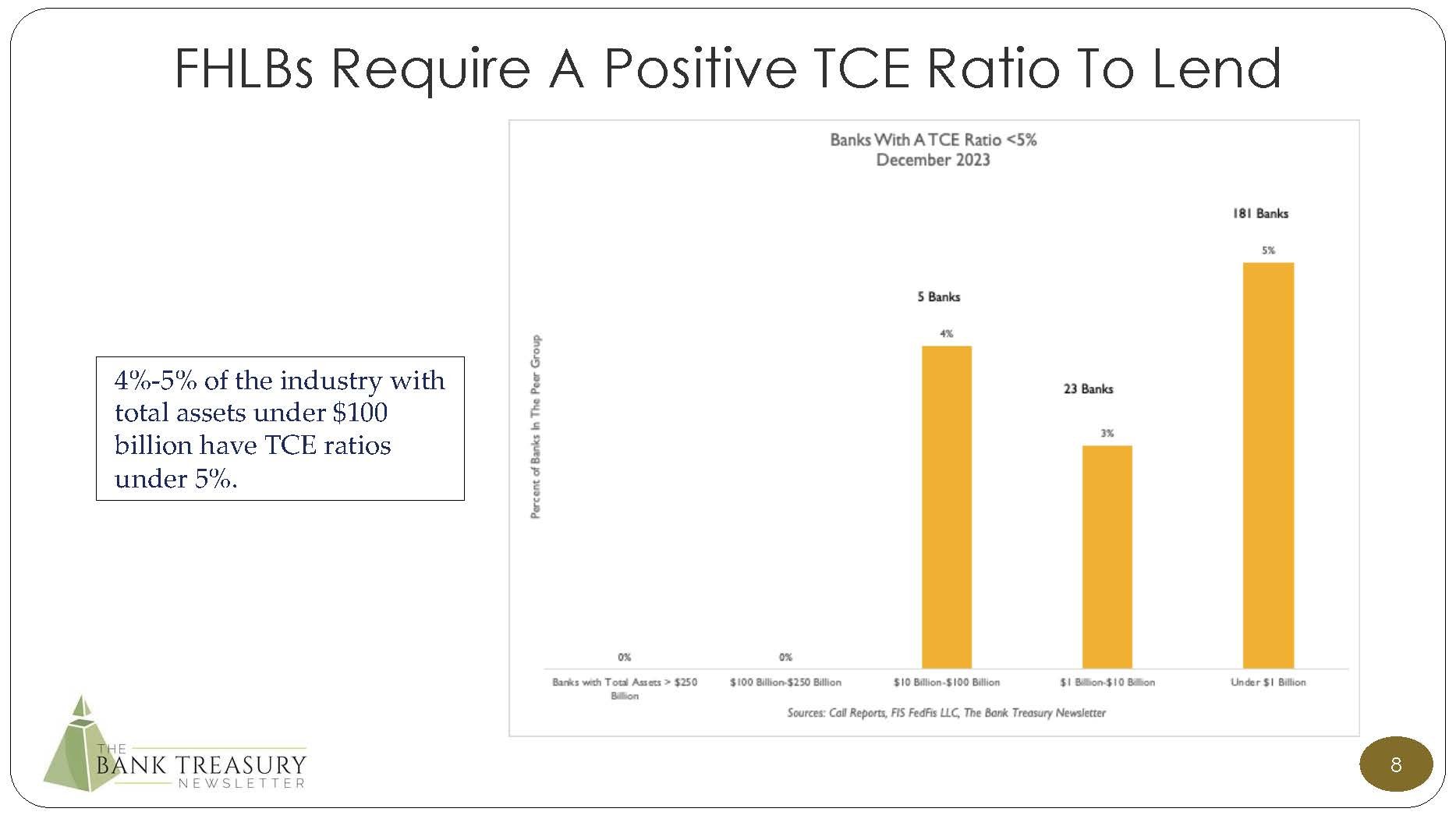

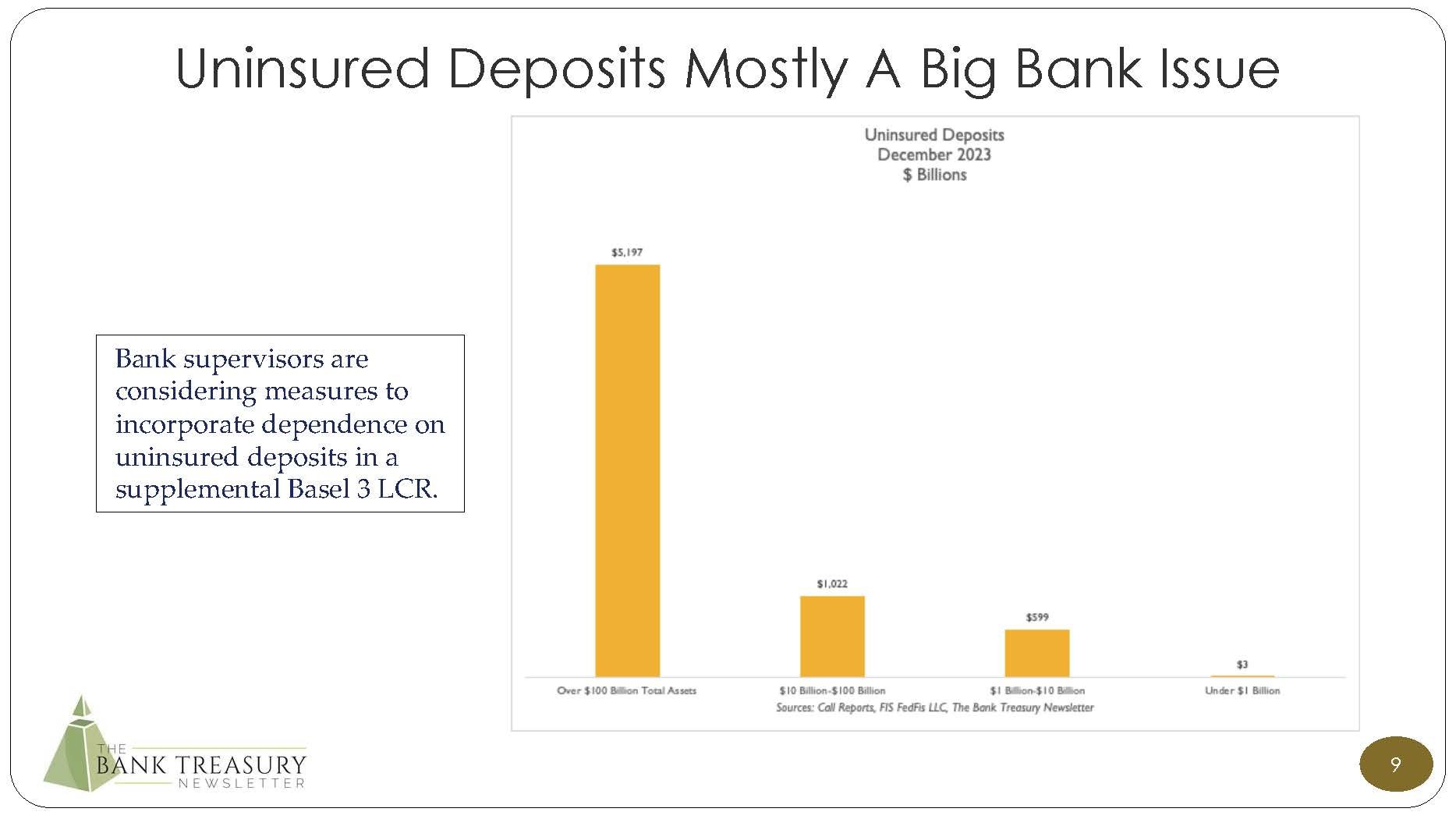

However, bank supervisors are no less anxious than they were last year. Based on Chairman Powell's testimony to Congress this month, the Fed's Basel 3 Endgame proposal will be revised (translation, "watered down") in response to an unprecedented deluge of comment letters complaining of its cost and its effect on the economy and financial markets. However, management of in-scope banks with total assets over $100 billion believe that the final draft will require them to include Accumulated Other Comprehensive Income (AOCI) in their regulatory capital calculation, that it will place limits on bonds in Held-to-Maturity (HTM), and that it will add an additional shorter liquidity stress period under the Basel 3 Liquidity Coverage Ratio (LCR) that in-scope banks would need to satisfy with pre-positioned collateral at the Fed's discount window. Even without a final rule in place, bank supervisors are already using informal guidance to force banks to increase capital and liquidity.

The Fed's 2024 stress test includes two "exploratory scenarios" based on the crisis last year. But a good lesson for bank treasurers and bank supervisors from that crisis is that existential risks are rarely foreseen, and that the best defense against failure and contagion may not be so much a fortress balance sheet, but better governance, better communication, and better preparation through scenario planning for idiosyncratic tail risk. As everyone in the banking space knows, no two banks are alike or face the same risks, so one-size-fits-all stress tests are not the solution to reduce the risk of bank failures and contagion.

The Bank Treasury Newsletter March 2024

Dear Bank Treasury Subscribers,

History can be instructive, so this is how it happened. Julius Caesar was 56 years old when he walked into the Curia de Pompei, a conference room just off to the side of the Roman Forum and got himself assassinated by a knife-wielding mob of senators led by his protégé and confidant, Marcus Junius Brutus. The date was March 15, 44 BCE, also known as the Ides of March, and 2079 years, plus or minus a few days before last March's bank crisis.

He should have seen it coming, and some believe SVB should have seen it coming, too, but it is also understandable why both did not. Everything, in retrospect, seems obvious. The Ides corresponded to the full moon's appearance, so there were twelve Ides, the Ides of January, February, March, etcetera. But the Ides of March was special. It was auspicious. The Romans were very superstitious and sacrificed a lot on that day. They did a lot of feasting too and probably had lots of orgies, but you know those, Romans.

So, if he had been superstitious, he might have stayed away. But then again, there was nothing particularly unusual about his going to the Forum that day or any other day. He had overseen the place ever since he had declared himself "dictator for life" the month before. He was just going to work (work from home was not a thing yet).

On the other hand, he had been warned. He could have at least worn some armor. Calpurnia, his third wife, age 29, who had been married to him since she was 16, had dreams for an entire month before and again the night before about blood on some statues and begged him not to go. For some reason, she still loved the guy, even though he was two-timing her with Cleopatra, who was 26 and may or may not have looked like the late actress Elizabeth Taylor. Calpurnia was willing to lay it all on the line with her wayward husband, and in a moment of brutal frankness after he initially brushed off her concerns, she told him (according to a transcript courtesy of some excellent reporting by William Shakespeare),

"Alas, my lord, your wisdom has been undermined by your overconfidence. Don't go out today. Tell people it's my fear that's keeping you inside, not your own. We can send Mark Antony to the Senate to say you are not well today. Please, I'm down on my knee, asking you to have my way in this matter."

Boy, she must have loved him to get down on one knee for him despite his hubris! "Don't go, be smart and work from home," she said. "Trust me." And the good-for-nothing listened to her. At least, that is what Shakespeare says happened. "Okay, I will not go," he told her, not in so many words. He would work from home. After all, he was the boss! It is good to be the boss. But then one of his aides (who also was one of the assassins) came to Caesar's portico (which was an ornamental porch the Roman architects of the day were big into) and told him he needed to grab his toga right away and come directly to the Forum because everyone was at the 8 AM meeting but him.

Everyone was waiting. And didn't he know the date? It was his calendar that everyone was just starting to use. He was the Julian in the Julian calendar, after all! Forgetting everything he had just promised Calpurnia, he ran off (sans armor) and met his surprise "et tu, Brute" moment for all eternity. His death on the Ides of March altered the course of history, the same way supervisors are saying the failure of SVB, and the bank crisis last year altered the course of bank supervision. What has been seen can never be unseen. If he had only listened, paid more attention to the funny looks Brutus was making, read the room, gone to work any other day but the 15th, or at least brought his breast plate armor with him, Shakespeare's "Julius Caesar" might not have been included in your editor-in-chief's mandatory high school reading curriculum, to say nothing about the course of history ever since.

Although the Ides of March in 44 BCE was on the 15th of the month, western Christendom switched to the Gregorian calendar in the 18th century. Gregorian dates no longer align with Julian dates and the full moon. Thus, the full moon and the Ides fell this year on March 24. Still, ironically, a year ago, using the Julian calendar, the full moon and the Ides of March fell on Tuesday, March 7, a fateful day in bank treasury history that began a series of fateful days.

In all fairness, there were bad omens in the financial markets long before March 7, the day that the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) began the process that would lead to the shutdown of Silvergate Bank, that would in turn lead to a bank crisis that caused four major banks to fail virtually overnight. Silvergate's days were numbered since Sam Bankman-Fried's FTX crypto exchange collapsed in November 2022. That was the beginning of the end.

Silvergate was connected to FTX because it ran a crypto payment transfer service that depositors could use to invest in crypto such as the FTX digital token, and it had credit exposure to the exchange. It was the quintessential go-go bank printing record profits right up until FTX's collapse. After FTX crashed and burned, crypto investors ran for the proverbial hills pulling $8 billion in digital deposits out of Silvergate within a day. It limped into its Q4 2022 earnings call on January 6, 2023, on its last legs.

On March 8, the day after the full moon, otherwise known as a waning gibbous moon, Silvergate's management announced in the morning that the bank would liquidate its remaining $4 billion balance sheet and shut down. The news was no surprise to the financial markets. Investors could see this coming, and despite the suddenness of the turn of events, the absolute size of the bank's balance sheet did not present an obvious threat to the U.S. financial system. At least not then, though, from the vantage of a first anniversary of the line of contagion that went from Silvergate, to SVB, to Signature Bank, New York (SBNY), to First Republic Corporation (FRC), and finally to Credit Suisse (CS) seems clearer.

The markets were a little shaky on March 8 after the Silvergate announcement, which might have dissuaded SVB's management about the timing of its announcement. Plowing ahead, SVB announced that it would restructure its AFS portfolio, incur a $1.8 billion loss that would wipe out Q1 2023 earnings (had it made it long enough to report them), and raise $1.25 billion in common on top of a $0.5 billion private placement of preferred. If only management had been paying more attention to the news.

That is true; there was no direct tie between SVB, Silvergate, or FTX. SVB was not a crypto bank. But the thing about black swan events is that they start as a series of innocuous, isolated, seemingly unrelated issues that suddenly coincide and cause so much damage. It is never just one thing. There are always omens and warning signs, and you just need to see them and connect the dots.

Which neither Caesar nor SVB management did. Caesar's days were numbered long before the Ides of March, but he could not see it or imagine that the odds were cumulatively stacked against him. Caesar had started on the trail to his bloody end by first defying the Senate and crossing the Rubicon. Then he decided he wanted to be king. He took a lot of risks, and annoyed his competition until they could not take it anymore. And it was not as if assassinations in the Roman Senate were something new. Public figures like him had been getting killed in that place ever since the Gracchi brothers in 120 BCE. So, he could have seen it coming if he had looked.

The trail that led to SVB's failure and the following bank crisis stretches back even before Silvergate and FTX. It started with rate hikes and the beginning of quantitative tightening the year before.

A year before the bank crisis, on March 16, 2022 (the full moon was on the 18th of that year), the FOMC raised rates for the first time since it had cut them to 0% in March 2020. In retrospect, if SVB had decided right then and there to exit out of its bond positions it might still be here today. Its Matters Requiring Attention (MRAs) and Memoranda of Understanding (MOUs) from bank examiners concerning its interest rate and liquidity management deficiencies would never have seen the light of day, and the bank would not have become a classic what-not-to-do, bank treasury 101 case study. Alas, like Caesar, it went to its press conference overconfident that everything would work out against better judgment that it would not.

In March 2022 before the first hike by the Fed, the 10-year Treasury yielded 2%, and the 30-year mortgage hovered around 4%. At the short end of the curve, the Fed was paying 20 basis points for overnight reserve deposits. Owning bonds in a 0-rate environment meant believing that the lowest yields seen in a decade with nowhere to go but up were a buy. But sitting in cash and giving up yield was a lot to ask from shareholders who were already fretting about how the industry would generate returns in a low-rate environment and how much more so with SVB, with its balance sheet concentrated in bonds, not loans.

Today, to sit in cash is to be in nirvana, a unique moment when bank treasurers can sit back, do nothing, and get paid handsomely by the Fed for no trouble at all. How often does that happen in a bank treasurer's career? But back in March 2022, for a position in cash to have paid off, you had to have a lot of faith, beyond all the economic and rate projections that were floating around at the time, that the Fed was going to go higher and faster than anyone had ever expected, and that was tough sell to the Board of directors at SVB and a lot of other banks, as well.

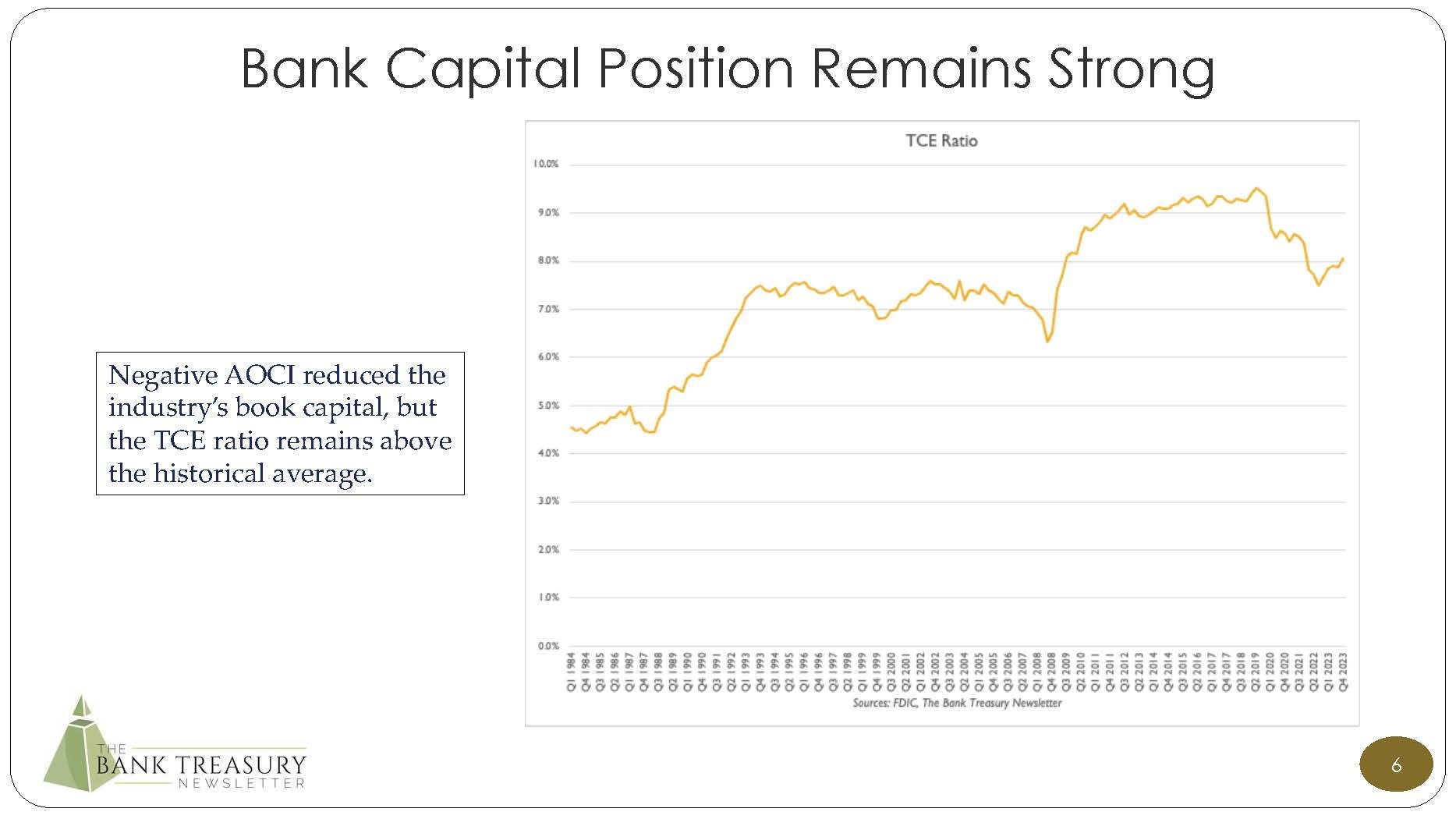

But the Fed went higher and faster, and its hikes sank the fair value of investment portfolios, which created accounting and regulatory capital headaches for SVB, given its large concentration in bonds. And at first, negative Accumulated Other Comprehensive Income (AOCI) was no big deal for banks like SVB that were under $250 billion. The regulators let them opt out from counting AOCI in regulatory capital, even if it was still included in Generally Accepted Accounting Principle (GAAP)-based capital measures, such as the tangible common equity. Historically, AOCI was never a significant number plus or minus against the bond portfolio, nothing of the magnitude that soon followed (as shown in Figure 1).

Figure 1: Fair Value of the AFS Portfolio, % of Historical Cost

But negative AOCI worsened. And on top of that problem, by March 8, 2023, deposits had gotten very competitive, and treasurers all over the industry were fretting about deposit outflows to the money markets and other banks. Depositors, accustomed to earning nothing, at first did not pay much attention to the rate hikes, and their inaction may have given SVB's management a boost in overconfidence that deposits would be sticky. Bank treasurers had planned to lag rate hikes on deposits as they had in previous cycles. But then depositors woke up and when they did, they woke up hard and fast, hard in demands for rate relief, and fast to other banks or money market funds when their bank was still in lag mode.

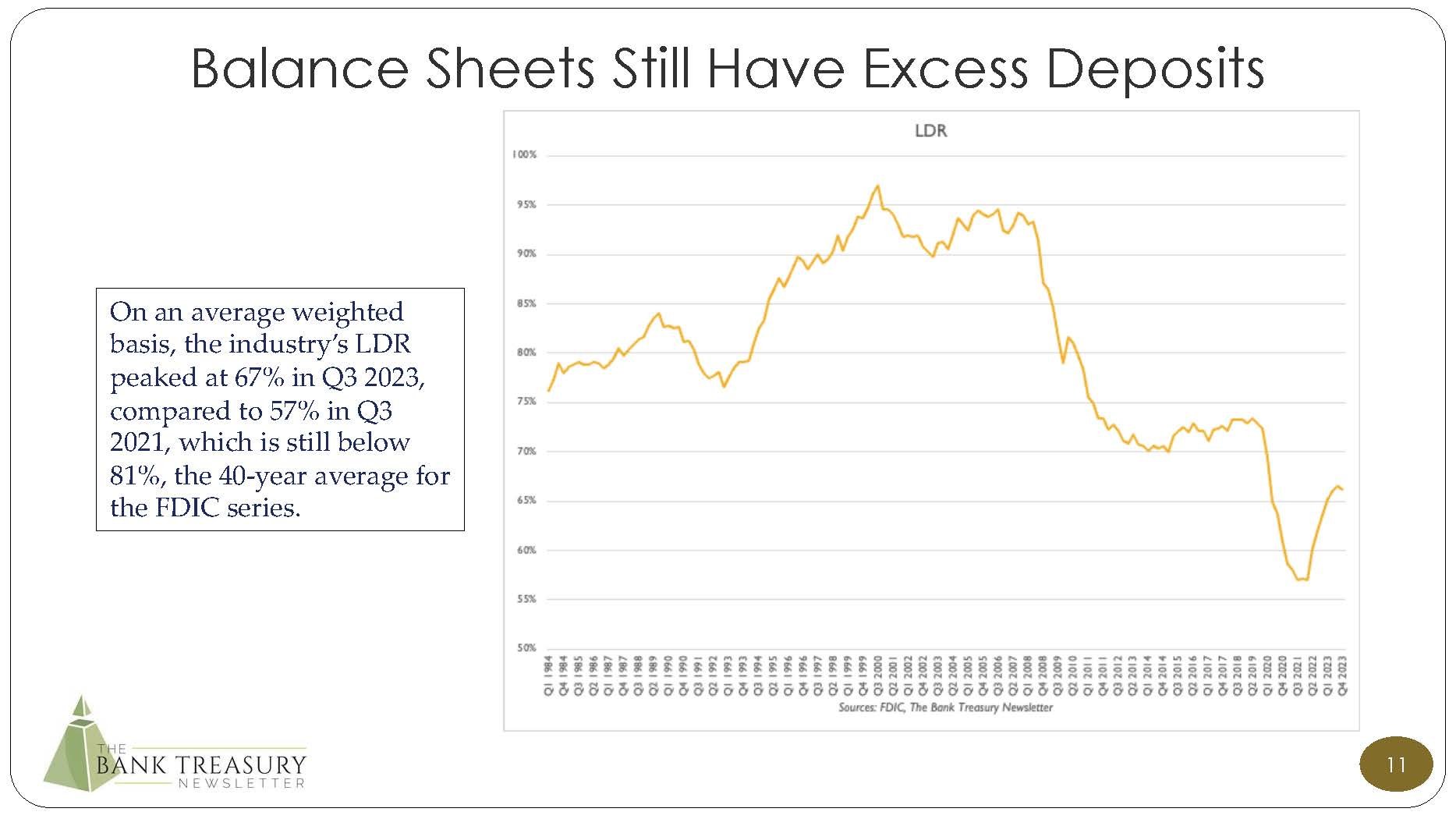

At a macro level, the runoff was not a total rout of the banking system. Total deposits, according to the Fed's H.8 data, fell from $18.4 trillion in April 2022 to $17.6 trillion by March 2023, less than a 4% decline, and even at their reduced level were still $4 trillion higher than they were before Covid. At the macro level, the system was still long a lot of excess deposits.

But over at SVB, the industry-wide deposit outflows and negative AOCI issues were catching up with a bank that had always had a niche franchise in the start-up, high-tech industry. It offered deposit and other banking services to a unique customer base, which tended to move large amounts of cash in and out of its accounts. To manage that volatile funding, unlike its peers, most of its financial assets were concentrated in U.S. Treasury and Agency MBS, instead of loans, a balance sheet that by most traditional liquidity metrics would be considered liquid.

Before analysts and investors ever paid much attention to AOCI, and the finer distinctions between AFS and HTM, before negative AOCI grew to nightmare proportions that undermined the proposition that bank investment portfolios are a store of liquidity, and before anyone made much of a distinction between insured and uninsured deposits, when unstable deposits were called brokered CDs, SVB's balance sheet was the essence of liquidity. It had twice as many deposits as loans, a far higher ratio than any of its peers. It was liquid because AAA government securities are supposed to be liquid, not assets that you suddenly find trading 10 points underwater. Besides, SVB's management knew its customers. They would never just run and never had. They were in and out, not cut and run. At least that was what it believed.

Unfortunately, the technology industry had just come off a very bad year. Tech stocks fell by 30% in 2022, way underperforming the major equity indices. It was not just the crypto market. Apple had had a bad year, Netflix was struggling, and frankly none of the FANG stocks were doing well. As venture capital (VC) pulled back, SVB's VC-backed depositors pulled deposits. They pulled them hard and fast.

From March 2022 to December 2022, SVB's deposit balances fell from $198 billion to $173 billion, which is a lot of deposits for a bank to lose on a relative basis in such a short period of time. And the deposits that stayed were not staying in noninterest-bearing accounts. No sir! Noninterest-bearing deposits fell by $47 billion, to $80 billion, while interest-bearing increased by $22 billion, to $92 billion, and so not only was SVB struggling with deposit outflows, but the deposits it kept were costing more.

Even with deposits costing more, the outflows left it with insufficient deposit funding to cover its underwater and very illiquid bond portfolio that equaled $110 billion, of which $91 billion was in HTM, and the rest was in AFS, on top of a $74 billion loan book. So, it went to the Federal Home Loan Bank for advances to plug its funding gap. But wholesale funding, unlike retail funding, does not come cheap, especially relative to noninterest-bearing deposit funding, so that weighed down on SVB's profitability even more, which woke up the rating agencies, which in their typical reactive style put the bank on review for a downgrade. After all, who really believes rating agencies when they say that they rate through a rate or credit cycle, but that is another matter.

SVB was in bank treasury terms, upside down, with its cost to fund exceeding the yield it earned on its assets. In bank treasury 101 they tell you to never ever get yourself into such a situation. SVB was in it big time, even if management was about to make everything worse by announcing a restructuring on the same day that Silvergate formally announced it would close, without ever considering how its uninsured depositors would interpret the news or worry they would decide it was a signal to run like the Silvergate depositors ran.

SVB was an accident waiting to happen, as the Fed's detailed report it published last May makes clear. It did not have a credible plan to deal with the Fed's hikes, the deposit outflow, and its underwater bond portfolio other than to expect rates to come down and that everything would work out in the end. Because it had seen or thought it had seen these rate cycles before and besides, it knew its depositors. But it had to do something about its funding and profit story, because if it did not fix the situation, another ratings downgrade would start to really hurt the bank's credibility with its depositors. So, taking advice from its investment banker, it decided on a sale and earn back restructuring.

A sale/earn back is no big deal, all it involves is some upfront pain followed by a payback period where you accrete the loss back through future earnings, generally three years. You sell some bonds, you book the loss, you buy new bonds with higher yields, and you earn back your loss over that period. Simple. Bank treasurers have been doing these trades before SVB and they have been doing them ever since, most recently in Q4 2023, as several bankers told the markets at an industry conference this month, The CFO of a regional bank based in the southeast was seeing a lot of rebalancing going on, especially in the last quarter, telling analysts,

"We're seeing a lot of banks rebalancing their balance sheets."

Most of these restructurings involved portions of the portfolio, and are opportunistic, as the treasurer of a larger regional bank in the southeast explained, "There were opportunities to make some relative value shifts within the portfolio length and duration a bit, which fits what we're trying to do with managing our exposure to lower rates through time… It's a pretty quick payback, around a 2-year payback. So, the financial metrics of doing that all look good in relation to alternate uses of capital like share repurchase, for instance. It's very accretive to earnings and tangible book value almost immediately. So those are things that we'll keep in our toolbox as we think about repositioning of the balance sheet through time as we need to react to changes in our balance sheet."

As SVB was signing the papers to execute the trade on March 7, the curve was set up perfectly and the economics never looked juicier, trading basically flat out to the 10-year. Thus, the current yield of the bonds sold would equal the yield on the short-term investment that replaced them. Economically, a bank treasurer would want to do this trade in size. And so, the next day, on March 8, with the moon doing its waning gibbous thing, and after Silvergate announced its wind down plans, with the markets a little jittery, SVB's management team, no doubt brimming with overconfidence, announced that it would do it all, trade its entire AFS portfolio in a sale and earn back. And big deal or not, its announcement was a stop-the-music moment.

Unfortunately, whatever SVB expected, its major uninsured depositors and shareholders did not take the news well and everything got completely out of control very fast. Trying to bar the doors the next day, at 11:30 AM PST the CEO asked everyone to stay calm, and he got runover by a mob of frightened depositors. He might have well screamed fire because $41 billion rushed out overnight and SVB was closed by the FDIC before lunch on Friday the 10th. Suffice it to say, the CEO could have done a better job of reading the room.

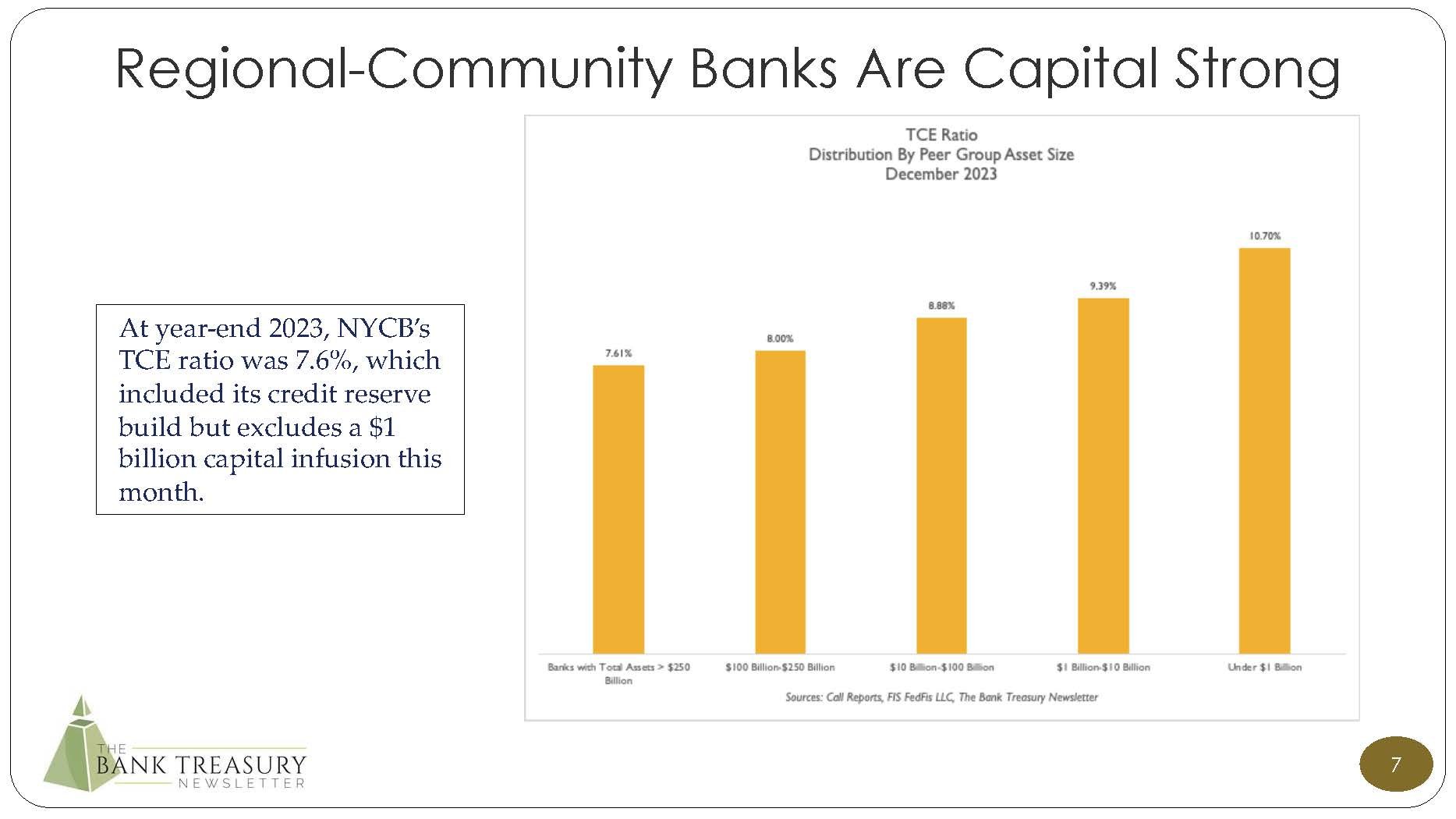

For the record, even without the capital raise it had planned but not executed, SVB was far from insolvent as it has been widely portrayed in the financial press, and would have reported at least a 6.6% tangible common equity ratio, including the pro forma $1.8 billion loss on the sale/earn back, at quarter-end. But that nuance has been lost, and well-capitalized according to regulatory standards or not, SBNY, FRC, and CS followed it over the cliff.

For a while regional banks became a toxic credit story. A year later, even if depositors have calmed down, regional banks remain suspect with shareholders and bank regulators. Indeed, the market is still waiting for another shoe to drop, and short sellers were rewarded for their bearishness when, on January 31 this year, a large regional bank in the metro NYC area, a bank which had always delivered on shareholder value and had historically reported excellent credit metrics, surprised the market with bad news concerning its exposure to multifamily loans. It then topped that news off with another announcement this month that it needed an immediate capital infusion.

Just for the record, as was the case with SVB when it failed, the bank's tangible common equity ratio equaled 7.6% at year-end 2023. This compared slightly below the 7.8% peer average, which on its face is hardly a bank with a capital problem that required an urgent infusion to remain in business. And, notably, unlike SVB, SBNY, FRC, and CS, not to mention IndyMac that former Treasury Secretary Stave Mnuchin turned into OneWest, this metro NYC bank has not failed.

But let's leave these stubborn details aside for a moment. What are the lessons learned one year after the crisis? One is that "shoot first, ask questions later" remains a go-to risk management strategy, especially for investors in financial institutions where transparency is never as timely enough as needed in a crisis. It was especially so with SVB's depositors. As Gary Tan, the CEO of a start-up called Y Combinator, one of SVB's depositors, told the Los Angeles Times on March 9 after meeting with SVB, "We have no specific knowledge of what's happening at SVB. But anytime you hear problems of solvency in any bank, and it can be deemed credible, you should take it seriously and prioritize the interests of your startup by not exposing yourself to more than $250K of exposure there. Your startup dies when you run out of money for whatever reason."

Here then is an indisputable lesson. Investors and depositors, basically the public, the people who maybe read the Wall Street Journal, but do not read publications like this newsletter, are not bank analysts. They do not get nuance, they really do not know what insolvent means, or how AOCI relates to Basel capital ratios. All they see is very bad news, not an issue that will naturally be resolved over time.

Because all SVB needed was time. Its HTM portfolio was bleeding off at $2.5 billion a quarter, so in nine year for sure, its underwater portfolio would accrete back to par. The average duration of the AFS bonds it sold was 3.6 years, nothing crazy, despite such depictions in the press. All the depositors had to do was stay calm. But when uninsured and nervous depositors smell smoke, do not expect them to remain calm and carry on. Expect to have a run on your hands.

In the immediate wake of the crisis, uninsured depositors learned to be more mindful of their exposure to their primary bank (Figure 2), and reduced the balance of their accounts, or demanded compensating collateral. As the memory of the crisis recedes and depositors evaluate the cost of collateralized deposits, the CFO of a regional bank in the southeast told analysts that the subject is not as hot as it used to be, and that uninsured depositors are starting to go back to keeping higher uncollateralized balances at the bank,

"We've seen the pendulum swing back since May and June when everyone was asking about it. And we did a lot of collateralized deposits. We did a lot of sweeps. And that came with a charge to the client. So, as the environment has normalized and there's not that fear of bank runs anymore, we've seen a lot of our clients say, okay, I want my money back and I'm not going to pay to add the additional insurance anymore."

Figure 2: Uninsured Deposits, % of Total Domestic Deposits

There are encouraging signs that deteriorating trends in deposits are finally stabilizing. The CFO from a regional bank based in the southeast told analysts that competition is less intense this year than it was last year,

"We're not seeing the competition that we saw last year. We're not seeing any banks put up double-digit deposit growth. We aren't seeing huge promo rates out there."

The treasurer of a larger regional bank also based in the southeast, told analysts that he had expected the pressure to ease, going into the year,

"We came into the year really messaging that over the course of the first couple of quarters that we're going to see deposit costs and balances stabilize. That's still our expectation."

Up north, the CFO from a large regional bank told analysts that competitive pressures were easing faster than the bank's management team had expected going into 2024,

"When we put our plans together in the fall, we anticipated deposits would be very competitive. I think what I have seen, and I think what the industry has seen is much more rationality in the marketplace. And you're seeing people trying to grow deposits, but doing it at a slightly lower promotional rate, which bodes well, I think, for the industry."

Up further north, in New England, the CFO from a regional bank saw stability in deposits flows and pricing,

"We're seeing very, very solid stabilization."

Stable was the word according to the CFO from a regional bank in the Midwest, who reminded analysts about another bank treasury 101 rule that says the best way a bank can count on stable deposits is to stay close to its depositors,

"We saw relatively stable deposits…I think it's because of our reputation, the relationships we built, we were in touch with our customers letting them know that we were safe and sound. And if they need that extra insurance coverage, we could help them get that…We spend a lot of time talking to our customers, and that's where relationships matter."

And in the long-run, as the president and chief operating officer from a western-based regional bank told analysts, after suffering deposit outflows in the wake of the bank crisis, he had confidence that deposits are always going to grow with the economy,

"Deposits will grow over time…the industry and for us. If you're a healthy banking company, notwithstanding pandemics and volatile Fridays, like March 10, your deposits will generally grow at the rate of the money supply or better."

When the Fed finally starts to cut rates, depositors will not forget higher rates so soon. This is a lesson in human behavior. The graph in Figure 3 shows how noninterest-bearing deposits are now back to where they were relative to total deposits in early 2020. The CFO of a regional bank in the southeast explained how depositor thinking has changed for the long haul, and was skeptical that rate cuts will lead to an immediate shift back by depositors to hold higher noninterest-bearing deposit balances,

"I don't think we're going to see much change. People are very sensitive to rates. They know that their money is making money now. And so, whether it's 5.25% or 4.25%, or 3.25%, they're not going to leave money in their checking account the way they did for a decade. Near 0 interest rates for a decade made them indifferent. The pain of transferring your money from your checking to your money market… wasn't worth it. Now it's worth it. Now it's worth it… It's worth it for corporate treasurers looking a week out and saying how much money do I need in our DDA account versus how much I can sweep into a money market. I don't expect that we're going to see a big shift back to DDA in the coming years provided we stay with higher interest rates."

History is supposed to be instructive, to tell the student what to do, what not to do, and what to look out for because it will happen again and again. But history depends on perspective, which differs between the way bank treasurers, investors, and bank supervisors remember it.

Bank treasurers maybe learned to never sit in a bond position when the Fed is raising rates, no matter how much better it pays than sitting in cash, no matter how much bank analysts complain about excess deposits and disappointing earnings per share. The lesson is that banks are cyclical. And another lesson might be that the bond portfolio is not always a great store of liquidity. Traditionally, a bank's investment portfolio serves three purposes, as described by the CFO and chief administrative officer of a large regional bank in the Midwest,

"Our objectives for the investment portfolio, are a store of liquidity, a tool to manage interest rate risk, and then an earnings generator in that order. And we are consistently thinking about it that way and making sure that the portfolio is positioned to manage liquidity, capital, and earnings."

Figure 3: Noninterest-Bearing Deposits, % of Total Deposits

But sometimes, the investment portfolio is not a great store of liquidity, or a good tool to control interest-rate risk and can seriously dent earnings per share. Sometimes cash is king for a reason.

Another lesson for bank treasurers is that granular deposits and borrowing capacity are the key to surviving a liquidity crisis. As the president and chief operating officer of a large regional bank based in the west told analysts,

"One of the biggest lessons was the importance of granularity in deposits and the importance of having borrowing capacity at the Federal Reserve and the FHLBs that is instantly callable. You can instantly access it. And fortunately, we had that instant access back in March, but we have it even more now. And I think that’s an important liquidity management discipline.”

Bank supervisors have a different perspective from bank treasurers and investors and learned different lessons. They realized they are not good at identifying risk even when it is staring them in the face. Consequently, they now insist that the banking industry needs more risk insulation, which means more capital and a larger stock of liquid assets. As Michael Barr testified last July about the proposed Basel 3 Endgame,

“Events over the past few months have only reinforced the need for humility and skepticism, and for an approach that makes banks resilient to both familiar and unanticipated risks.”

Which means that allowing banks with total assets between $100 billion to $250 billion to opt out of counting AOCI in their regulatory capital has got to go. The CFO of a large regional bank in the Midwest saw some significant changes coming on the liquidity regulation front, telling analysts this month,

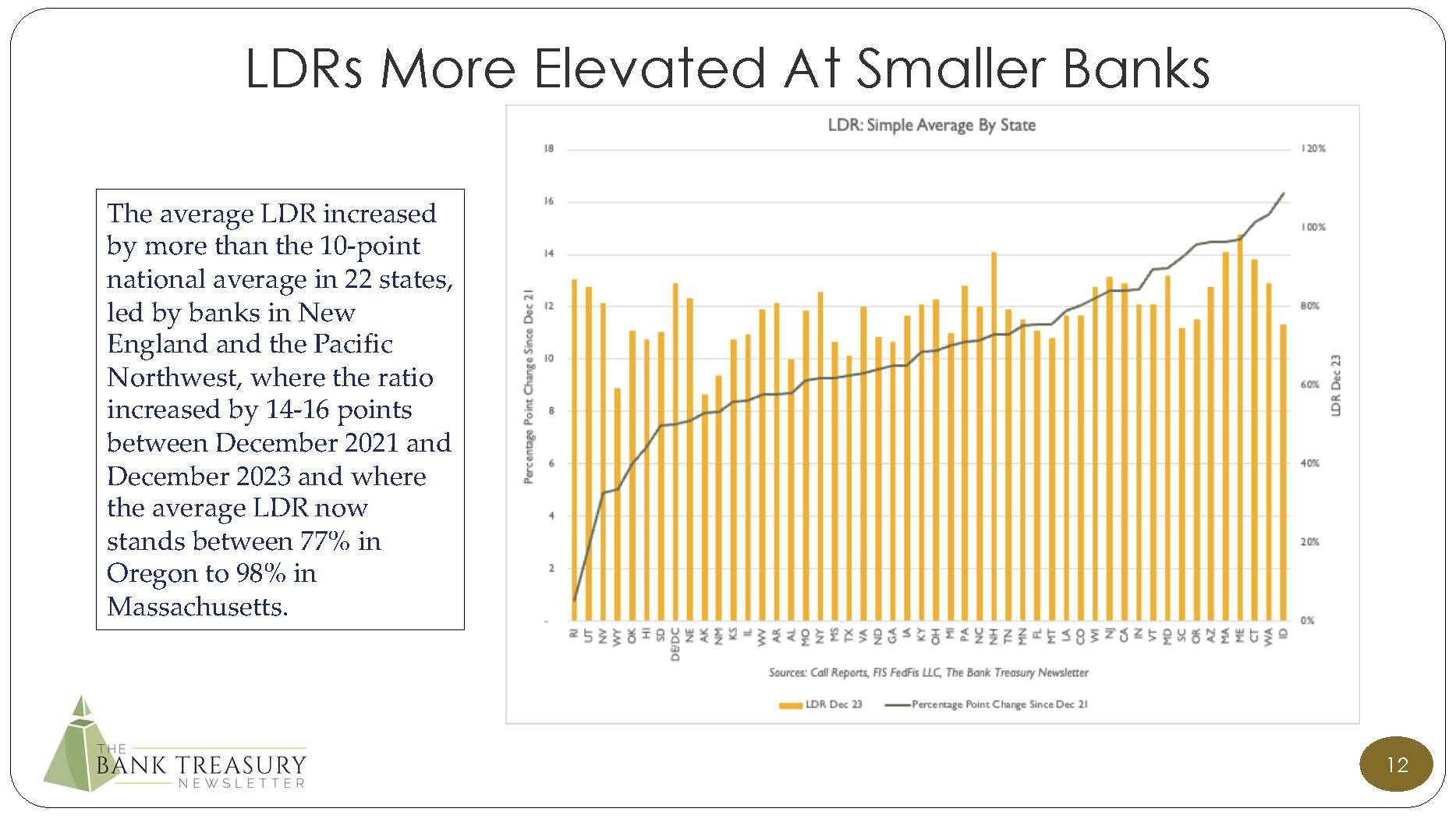

“We hear that CAT 1 LCR requirements are going to push down to the $100 billion institutions. And as part of that, some enhancements to the outflow assumptions…some additional runoff with uninsured deposits…And the other component we're hearing is…associated with HTM and some potential cap or haircut…that qualifies as part of your liquidity buffer…We are hearing that there might be a new metric that they put in place, some type of uninsured deposit coverage ratio, thinking something like maybe cash and discount window capacity needing to be up more than 100% of your uninsured deposits.”

A bigger, better fortress balance sheet will stop contagion, calm a public accustomed to running at the first smell of smoke. As the Vice-chair continued in his testimony, the events that led to the crisis that took down four banks so quickly, teaches that,

“We need to be careful about thinking about contagion.”

Indeed! Which means, as far as he is concerned, that the whole business with tailoring regulations and treating a $100 billion bank different from a $250 billion bank, which for the record was mandated in the 2018 legislation, S.2155,"“Economic Growth, Regulatory Relief, and Consumer Protection Act"” needs rethinking. Banks in this asset range, and possibly even small banks, when they fail, can cause a systemic crisis, he told Congress,

“Our recent experience shows that even banks of this size can cause stress that spreads to other institutions and threatens financial stability.”

But maybe another lesson is that aggressively pushing tighter regulations too fast will not get supervisors where they want to go. Because the Basel 3 Endgame proposal now appears to be stalling, at least enough to delay a final rule before the end of 2024. Fed Chair Jay Powell told the House Financial Services committee this month that he had seen a deluge of negative comments on the proposal, how it would stunt credit access, and create all kinds of problems in market liquidity and trading efficiency. Thus,

"We do hear the concerns and I do expect there will be broad material changes to the proposal."

Of course, regulators do not need rules to change guidance. Bank treasurers are telling the newsletter that examiners are more skeptical about their risk management practices and are being asked to prove they have the proper controls. Guidance may not be regulation, but it is just a technicality when a bank examiner wants a bank to conform to new guidelines, even when bank management can show why the guidance is misguided.

The problem with lessons learned, as Fed governor Michelle Bowman said this month, is that they are frequently based on a flawed perspective, caused by the rush to identify lessons learned. Bank supervisors have already made changes in guidance that can be disruptive, especially for institutions that had always passed their exams with flying colors and now suddenly find themselves defending their bank against MRAs and MOUs that make no sense. Changes in exam procedures have already happened, she told the New Jersey Bankers Association Annual Economic Leadership Forum, in Somerset, New Jersey, this month,

“These changes largely occurred after the bank failures in the spring of 2023 and the ensuing banking stress. In part, the changes in supervisory practices may be attributable to flawed post-mortem reviews conducted in the immediate aftermath of these failures. Many of these reviews suffered from serious shortcomings, including compressed timeframes for completion and the significantly limited matters that were within the scope of review. Nevertheless, these reviews were, and continue to be, singularly relied upon as a basis for resetting regulatory and supervisory priorities.”

After Caesar's assassination, Rome entered a dark age of civil wars and deadly proscriptions, much like in the days of the French Revolution and the terror. SVB's failure and the bank crisis last year unleashed a similar reign of terror on the banking industry by bank supervisors embarrassed by their inability to prevent the situation and intent never to let it happen again. As she continued,

“I worry that the mere fact of bank failures and the material banking stress we experienced last year has been interpreted as blank check to remake supervision as a blunt instrument, one that ignores the unique characteristics of each firm and the benefits of an approach that prioritizes engagement and communication between banks and examiners.”

A key conclusion in the Fed's review of the failure of SVB was that tailoring and calibrating, as mandated in the 2018 legislation, prevented bank supervisors from properly supervising SVB. For example, due to a quirk in the rules, SVB was not subject to the Fed's annual stress test in 2023, even if the severely adverse scenario was a best-case scenario for SVB as its assets were mostly AAA government securities, and its greatest vulnerability was rates higher for longer. As the Fed governor continued,

“One prominent argument raised shortly after the failure of SVB, and which has become a driving force in regulatory reform efforts, is that the Board's approach to tailoring was to blame for the bank failures and broader banking stress. The argument is that a major factor contributing to the bank failures was the implementation of S. 2155, the statutory mandate to tailor regulation and an accompanying shift in supervisory policy.”

Before regulators turn more regional banks into poster children for what happens to those who resist inadequate guidance, they should look at why bank supervision fails to prevent bank failure. Some of that is on management because SVB did not have good governance, and there was no excuse not to have tested its credit line to the discount window. For sure! However, some of the blame for the crisis last year is on supervisors in different federal and state agencies who utterly failed to communicate and cooperate. As she continued, there was no evidence that S. 2155 was to blame,

“As I have noted many times, I find little evidence to support this claim. While couched as a critique of the execution of tailoring, this argument also seems to challenge the value of tailoring, asserting that a simple solution would be to unwind regulatory tailoring and eliminate risk-based tailoring in supervision. Taking ownership and accountability of the supervisory issues that significantly contributed to the banking system stress last spring enables us to look critically at the approach to regulation and supervision in the lead-up to these failures and appropriately address the shortcomings.”

Maybe another lesson that bank supervisors could learn from last year's crisis is to stop relying on stress tests based on past crises to identify vulnerabilities in the system. The next bank crisis is probably not going to be a commercial real estate crisis in office or multifamily and is probably not going to be in bank interest rate or liquidity risk management. It will probably not look like the Global Financial Crisis. The next crisis, like all the other crises in the history of the banking industry, will come from a direction that no one expects, even if in hindsight, it will seem obvious. As the CFO from a large regional bank in New England explained, the bank is well-prepared for past crises as outlined in the Fed's 2024 stress test scenarios,

“I think it will be fine. I mean I think that when we poke around and try to reverse model the exploratory scenarios…we end up with adequate capital across all of them…The exploratory scenarios look at what would happen if rates stayed much higher. And the way we model it, our rate positioning is neutral.”

Bank supervisors could also learn to appreciate that there is no infinite supply of equity that investors are willing to invest in an industry that consistently fails to generate shareholder value, and that under the proposed Basel 3 Endgame regulations, could generate even less. They might learn to not bullheadedly push forward with regulatory changes and guidance running roughshod over the industry and its investors, the potential disruption the changes might inflict on the industry and the markets be damned. Bank supervisors might also learn to read the room and how to avoid the public relations nightmare this proposal has become for the next time.

And everyone could learn to appreciate timing. There is a time to buy bonds and there is a time to sit in cash. There is a time to announce a significant restructuring of the bond portfolio and a time to wait for another day. And finally, there is a time when you do not tell a crowd of frightened, confused depositors to remain calm.

The Bank Treasury Newsletter is an independent publication that welcomes comments, suggestions, and constructive criticisms from our readers in lieu of payment. Please refer this letter to members of your staff or your peers who would benefit from receiving it, and if you haven’t yet, subscribe here.

Copyright 2024, The Bank Treasury Newsletter, All Rights Reserved.

Ethan M. Heisler, CFA

Editor-in-Chief