BANK TREASURERS IN NEUTRAL

Listen to an audio version of this newsletter on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Amazon Music, Audible, or your favorite podcast platform.

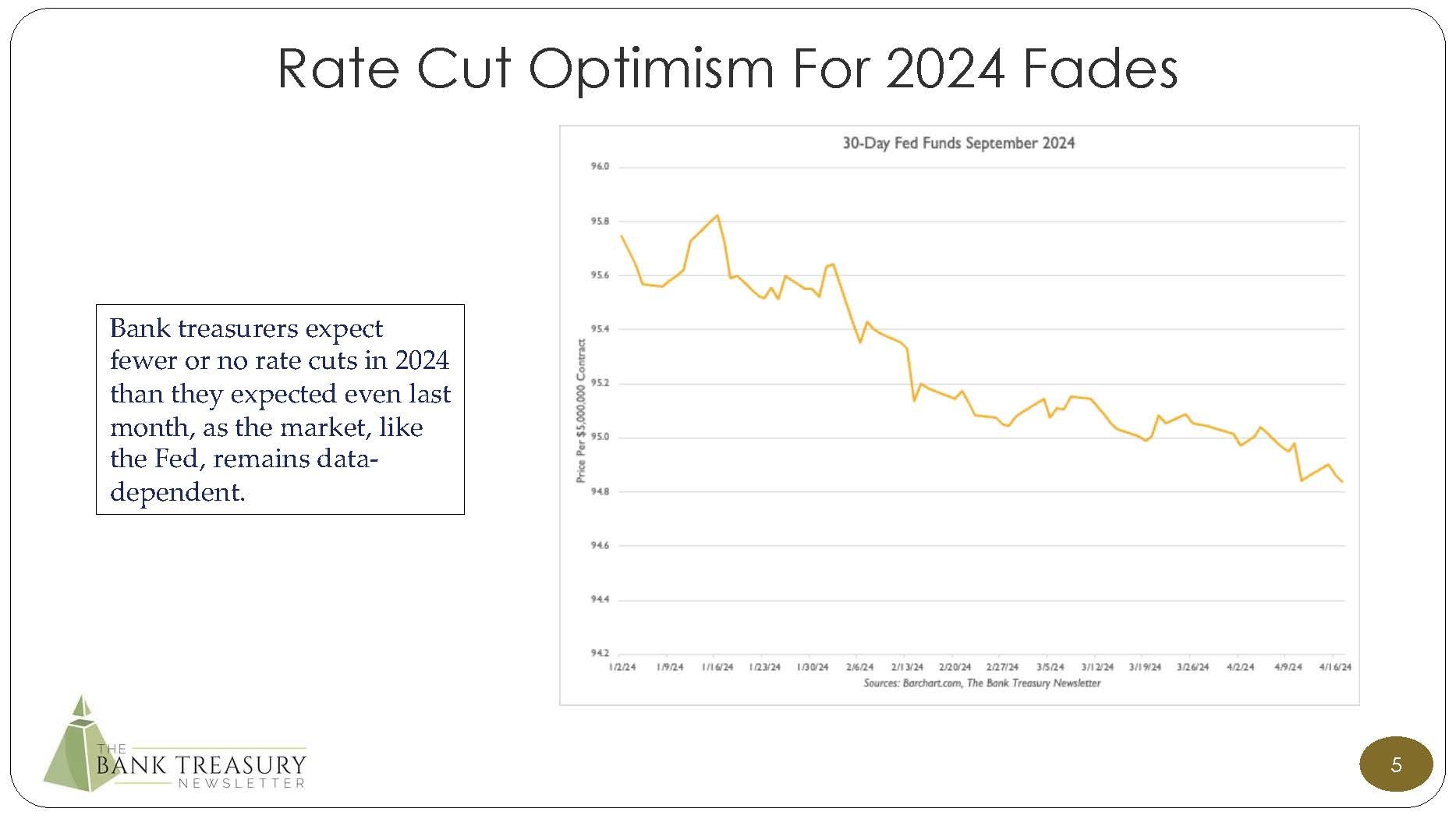

The Federal Open Market Committee’s (FOMC) most recent dot plot projected three 25 basis point cuts of the Fed funds rate before the end of the year, but bank treasurers are growingly skeptical that the Fed this year will cut even once. Even Fed officials sound like they are backing away from what they had just affirmed at their meeting last month. The inverted Treasury yield curve flattened by over 40 basis points in the previous few weeks, which may reflect a reassessment in the market on the prospect of rate cuts in 2024. As measured by the spread between 3-Month T-Bills and 5-year Treasury notes, the curve flattened from 120-130 to 80-70 basis points as longer-dated security yields rose and the front-end remained anchored.

As longer yields increased and the curve flattened, bank treasurers increased the duration in their bond portfolios, which they had been keeping very short in the wake of the bank crisis in March 2023. Suddenly, adding duration has started looking more attractive as an investment strategy. For example, the term premium on a 10-year 0 coupon Treasury, which had been as low as minus 75 basis points when Covid struck four years ago, topped over five basis points this month.

Cash is growing on bank balance sheets again, albeit modestly, as deposit balances at large and small banks reported in the Fed’s H.8 series increased last month by 1%, or by more than $130 billion. Loan growth, by contrast, was flat. The gap between deposits and loans for all commercial banks thus widened to $5.4 trillion, which, though well below where it peaked at year-end 2021 at $7.4 trillion, is still $400 billion higher than it had troughed six months ago.

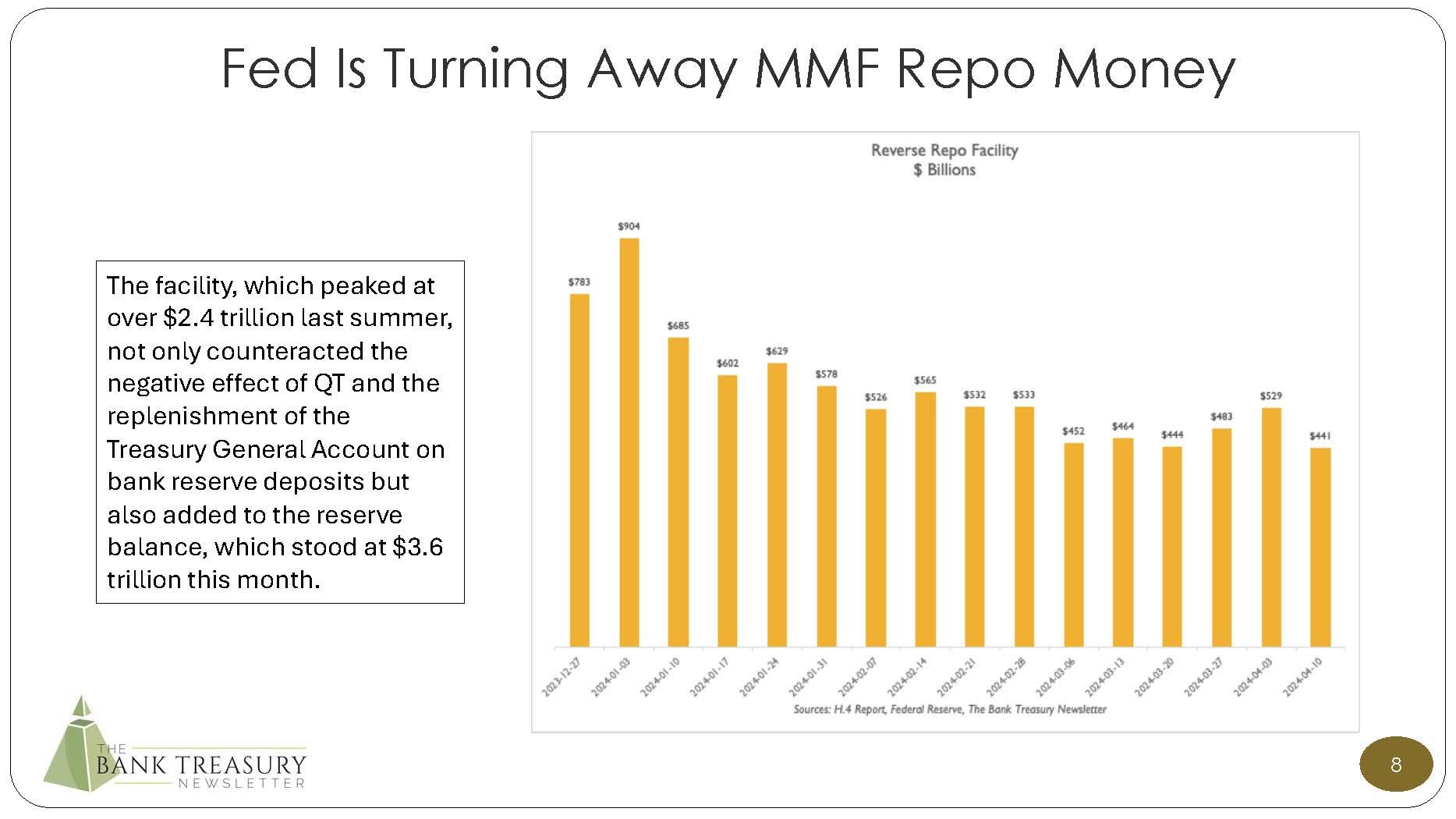

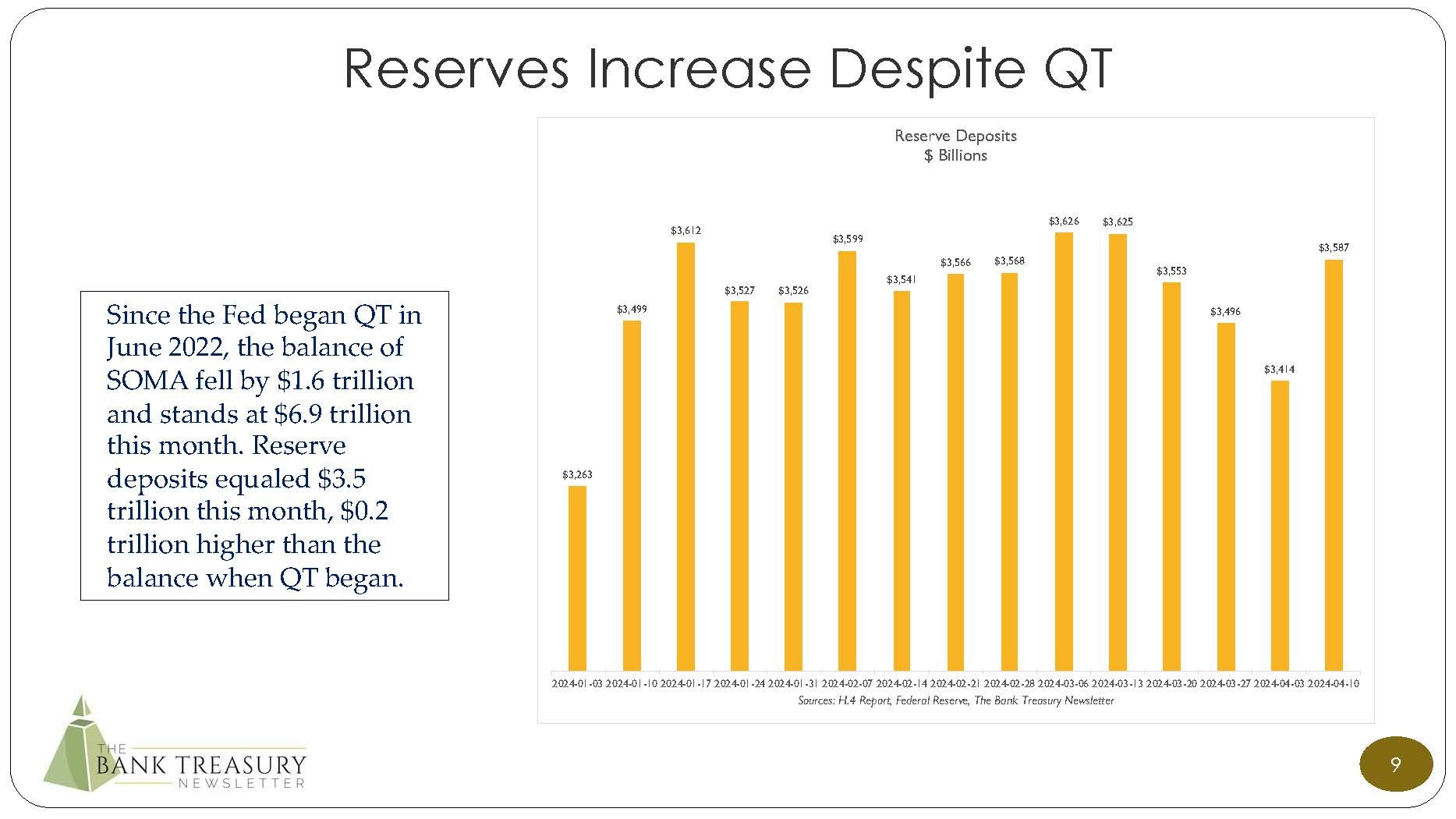

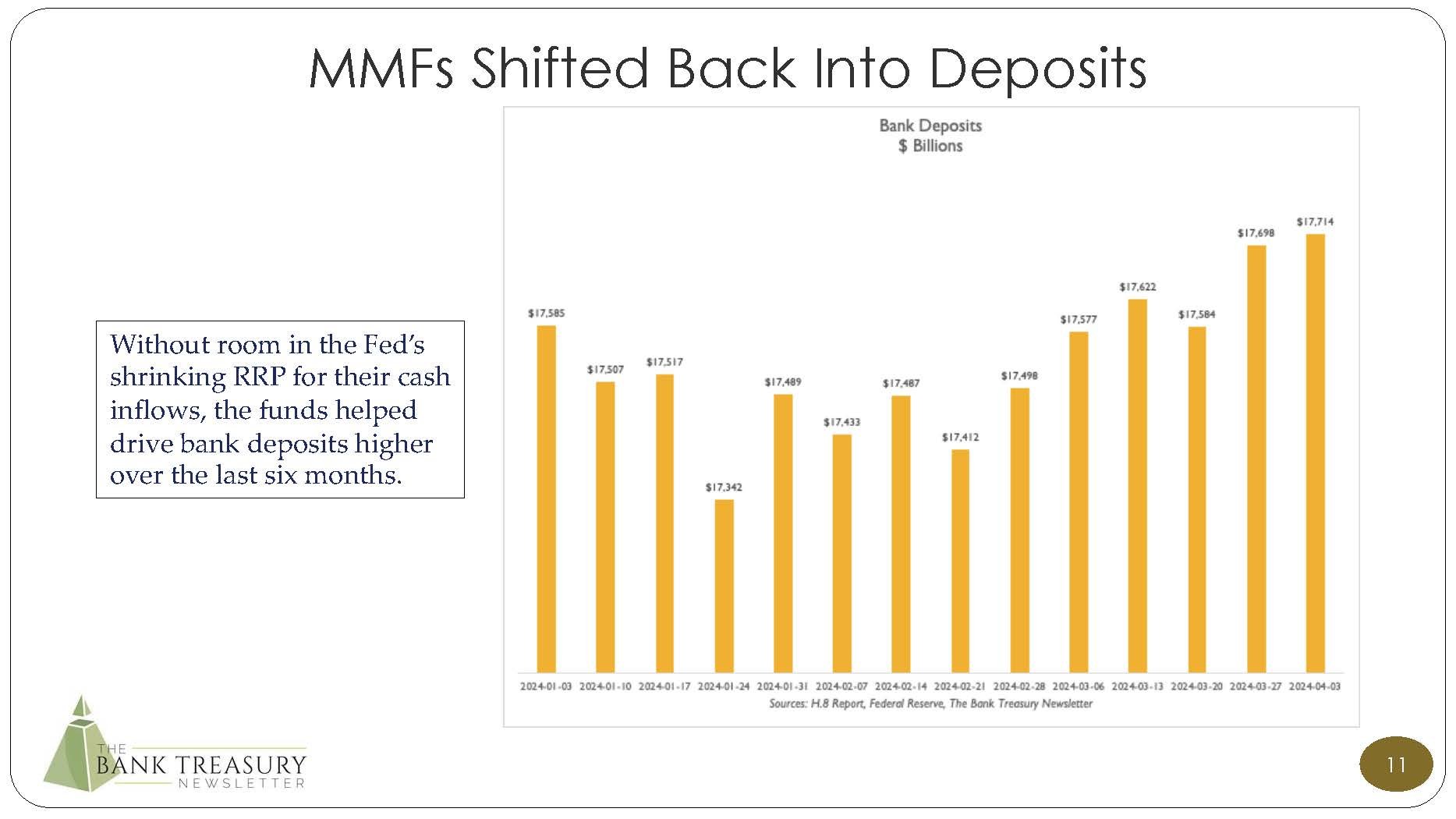

Some of the increase in excess deposits on bank balance sheets could be attributable to the latest developments with the Fed’s Quantitative Tightening (QT) operations. Over the last half-year, the Fed’s System Open Market Account (SOMA) fell by $0.4 trillion, to $7.0 trillion this month, which ordinarily should have been matched by a dollar-for-dollar decline in reserve deposits but instead mostly came out of the Reverse Repo Facility (RRP), which fell from $1.3 trillion to $0.4 trillion, while reserve deposits increased by $0.4 trillion, to $3.6 trillion. Instead of leaving their money at the Fed in RRP, money market funds went back into bank deposits.

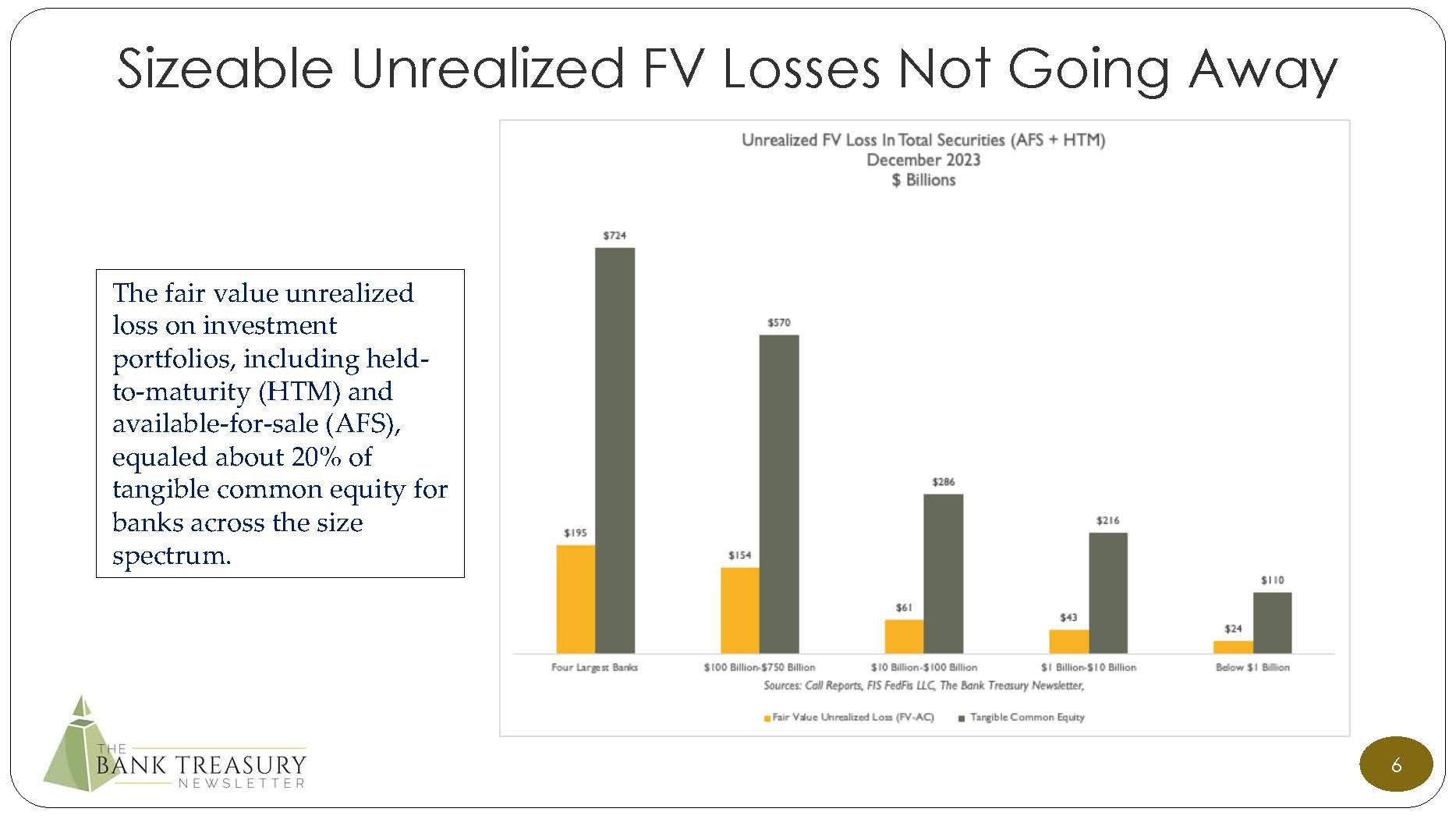

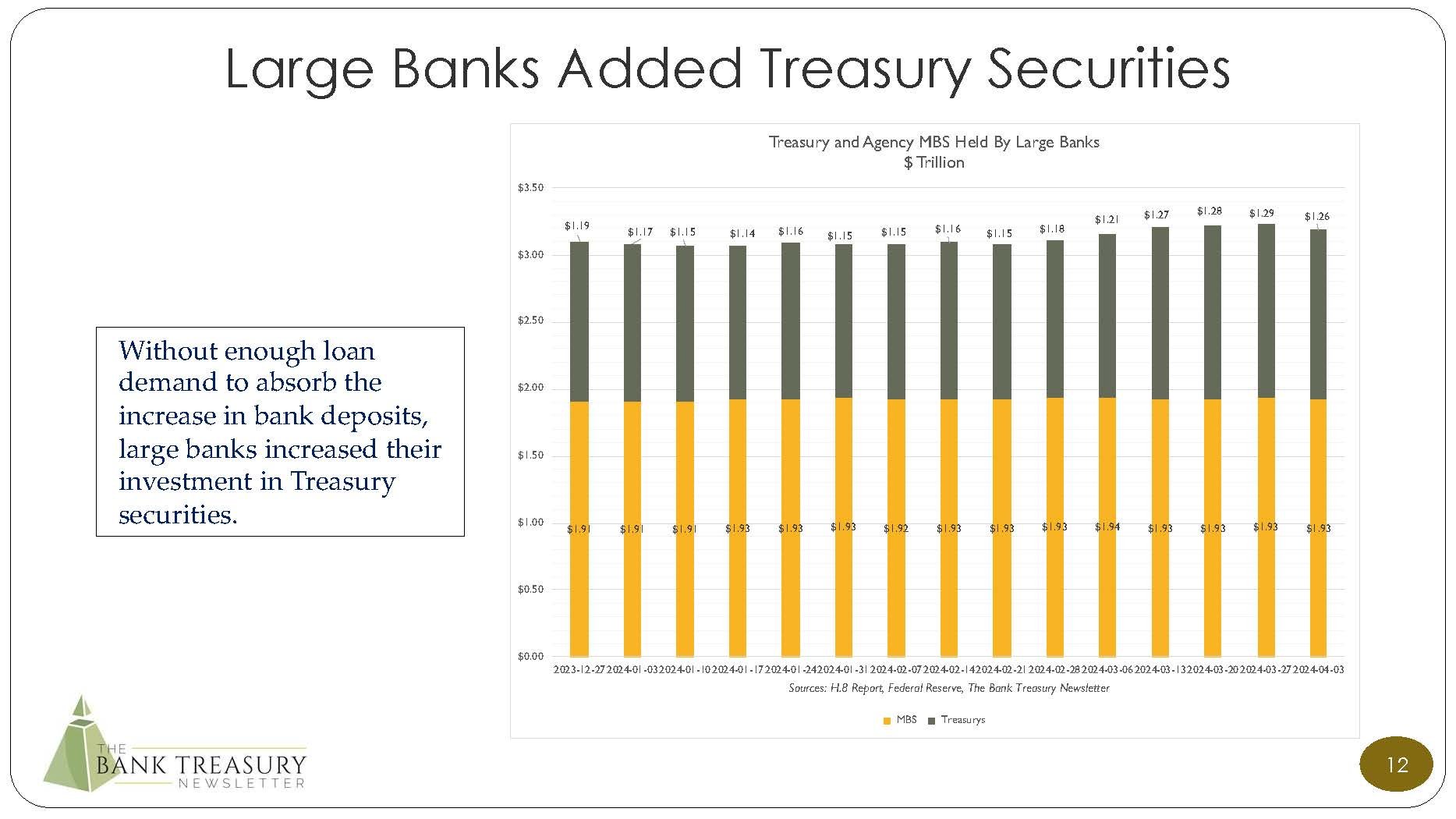

To absorb the increase, bank managers confirmed in their quarterly investor calls this month that they had begun to deploy some of their bank’s cash into securities, including Treasurys and Agency Mortgage-Backed Securities (MBS), targeting an average duration of around four years. But they also increased their reserve deposits at the Fed. Judging by the H.8 data, banks added securities and reserves at the Fed in Q1 2024 at a ratio of two to one. While banks added securities in the last month, higher yields and sinking bond prices have not helped do anything to address the drag on profits from their underwater bond portfolios. Counting together their held-to-maturity (HTM) and available-for-sale (AFS) portfolios, their unrealized fair value loss equaled $478 billion at year-end 2023, or 18 percent of tangible common equity after-tax.

In their message to investors, management addressed the declining trend in net interest income (NII) and net interest margin (NIM), saying that they expect both trends to level out this year regardless of the Fed’s decision about the number of rate cuts. This expectation builds on their assumption that bank balance sheets will have finished adjusting to the higher interest rate regime this year and that NII and NIM will return to trend. For now, however, consumers are still shifting cash from noninterest-bearing checking to CDs, which puts pressure on NII and NIM, and corporate treasurers are more careful these days about the money they leave in noninterest-bearing accounts.

Bank treasurers report that examiners have had conversations with them recently about setting up pre-positioned collateral at the discount window to use in an emergency. They are worried that pledging collateral to the Fed could limit their ability to pledge collateral for Federal Home Loan Bank (FHLB) advances and create other complications for day-to-day Asset Liability Management (ALM). Supervisors have fixated on the Fed’s discount window as an under-utilized resource for liquidity primarily because Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) had not tested its line when it failed.

The Bank Treasury Newsletter April 2024

Dear Bank Treasury Subscribers,

In truth, there are many Gravity Hills in the United States, and indeed in the world. The Commonwealth of Pennsylvania has four of them, and the most popular one, the one that has all the signs that lead you directly to it, is a detour south off the Interstate, around where 76 and 70 are joined up, in Bedford County, just south of Altoona and State College. In short, from a big city slicker’s perspective, Gravity Hill is smack dab in the middle of nowhere with no offense meant to the local inhabitants.

To get there, take SR 30 to the intersection with SR 96 and drive south to New Paris, a town with 192 residents and one traffic light. Pass by the charming Old Log Church and drive on the antique-covered bridge. Here is a sleepy part of the world, of hayseeds and haystacks, far from the madding crowd, if not the hustle and bustle of the big city. Not quite the Twilight Zone, but this is where you would expect there to be mysteries and cows that jump over the moon, a place where time seems to stop or even to run backward. Of course, a little imagination goes a long way out here.

On SR 96 South, make a right on Bethel Hollow Road (otherwise known as SR 4016), drive about two miles, pass the stop sign, now slow down but keep rolling, keep rolling, slowly, a little more, until you see the letters “G” and “H” spray-painted across the road. Drive a couple hundred feet down the hill until you see “GH” spray-painted again on the road. Stop the car, put it in neutral, and check your rearview mirror to ensure no one is behind you. Finally, release the brake and prepare to be amazed as you and your car roll back up the hill you just came down.

Most people repeat the procedure several times to see that looks are not deceiving, which they are because you are rolling down the hill. It looks like you are rolling up it because of an optical illusion related to the terrain. So, no, sorry, magic is not accurate. You cannot defy gravity or roll up Gravity Hill with your car in neutral. Gravity is still gravity, and time marches forward, even around Bethel Hollow Road. It is just a mirage that appears to be what it is not. The bank treasury world is filled with them.

Neutral, for example, is an illusion. Bank treasurers always talk about how their balance sheets are neutral, positioned to be insulated from changes in interest rates either way, up or down. Or so they seem to imply when they insist that whether the FOMC cuts once, twice, three times, or no times this year, they will still make their NII and NIM projections.

This is exactly what the CFO of a global bank promised analysts on his bank’s earnings call this month,

“At this point, we're neutral. So, if rates were to go up, rates were to go down, no material impact as it relates to our revenue.”

So said the CFO of a large regional bank in the northeast,

“We are neutral to interest rates right now. So, whether we get 2 cuts, 3 cuts or we get no cuts, we're going to be comfortable with the range.”

So, say they all.

Words like this might be reassuring in the boardroom, and it may seem that way to the public that NII and NIM will fly serenely through volatile interest rate storms. But in fact, bank balance sheets are regularly being knocked back and forth and tossed to and fro by waves of market uncertainty and surprises that affect NII and NIM. Even without pricing volatility, the balance sheet mix is in continuous flux as loans and deposits shift to the rhythm and timing of cash flows, in and out of fixed and floating rate loans, deposits, bonds, and other borrowings that feed and drive NII and NIM. So, nothing stands still, especially a bank’s interest rate sensitivity.

The ride will be a little bumpy, just as the Fed has been warning the trend with inflation will be, but it just will not seem that way to look at the reported quarterly numbers. You will not see the day-to-day, hour-to-hour, and even minute-to-minute volatility as cash flows in and out, off and on, deposit accounts are originated or closed, loan disbursements are made or recovered, and interest rate contracts reset up or down. But if you have a minute, go into the backroom and peek behind the curtain because that is where you will find the real wizards, bank treasurers huffing and puffing and spinning away furiously in place on their flywheels, sweating buckets to keep NII and NIM on track and in time for the next quarter’s results.

There are natural, fundamentally structured, asset-sensitive, and liability-sensitive banks. They have very different balance sheets. Some banks fund floating-rate commercial loans and other short-term assets with noninterest-bearing deposits that can be withdrawn on demand. These asset-sensitive banks make more money when interest rates go up than when they go down.

Then, some banks fund many long-term mortgage loans with liability-sensitive time deposits. They make more money when rates go down than when they go up. Savings and loans are like this. For obvious interest-rate risk and liquidity management reasons, no banks with long-term assets fund them with short-term liabilities. For reasons related to shareholder interests, there are also no banks with short-term assets financed with long-term liabilities. That said, given the current inverted yield curve, that would not be the wrong way to generate NII. At least in the short run until the curve flattens out.

But mind that there are no naturally neutral-sensitive banks, banks with a balance sheet mix that makes the same money whether rates go up or down. At least, not without some fancy ALM footwork to smooth over the gaps between their asset and liability cashflows. And even then, ALM can only adjust for volatility so much. The ride will be bumpy at some point, so a seatbelt is advisable.

Even if ALM could neutralize 100% of interest-rate risk (IRR) and make the ride so smooth, you could swear you were standing still, and no bank treasurer with long-term career aspirations would ever do so. The truth is that bank treasurers get paid to take IRR, not to sit in their foxholes resting on their overnight reserve deposits at the Fed, earning 5.4%. So, when they say neutral, understand that they do not mean IRR-free because nothing is ever IRR-free. You can always lock in a spread, but doing so does not generate NII growth or higher operating leverage.

Besides, banks are in the risk-intermediation business, so what is the point of setting autopilot for zero risk? Like all traders in the market, bank treasurers always assume risk. They are the bid to every offer and the offer to every bid, there to fund loans and take deposits, make long-term loans when rates are low, and take on long-term deposits when rates are high. Like traders, they get paid to assume IRR but also to set limits and abide by them.

Within limits, therefore, they sell options on both sides of their balance sheet for borrowers to prepay their loans whenever they want and for depositors to withdraw their funds or shift from noninterest to interest-bearing on demand. Deciding when to sit in cash, buy bonds, hedge, or not all involve some risk-taking and risk-setting. To quote Alan Greenspan, taking risks is the American way, proper for banks as it is for any other business in this country,

“It is this freedom to take on risk that characterizes our economy and, by extension, our banking system. Legislation and regulation of banks, in turn, generally should not aim to curtail the predilection of businesses and their banks to take on risk--so long as the general safety and soundness of our banking system is maintained.”

His was not an outlying opinion but reflected regulators' mainstream, prevailing attitude towards IRR and banking. An "Advisory" from the Fed on IRR in the banking book, dated January 6, 2010, practically echoes what the Maestro had said 13 years before,

“The regulators recognize that some degree of IRR is inherent in the business of banking.”

But!

But there are limits to everything. Bank treasurers get paid to set policies, decide how much IRR to take and when, and use their toolkits and experience to position the bank's balance sheet. These toolkits include derivatives, the investment portfolio, cash, FHLB advances, and other non-core funding financial instruments. Fund transfer pricing is part of the toolkit, which they use to steer the pricing of loans and deposits to align with their IRR policies and tolerances.

These tools used in unison make up their ALM toolkit, which operates much like a pilot's yoke, which they can deploy to pull IRR back or push it forward, to rein it or let it ride, and to plan to avoid the air pockets and headwinds, depending on what they see ahead through the windshield. Which, like the area around Gravity Hill, can be deceiving and lead you to believe your balance sheet is becoming more asset-sensitive when it is reversing and becoming liability-sensitive, fooling you into thinking your deposit beta is low and going to get lower when it is about to go to 100%. But they get paid to manage IRR, set limits, and watch the road ahead, even when they are in a cloud and cannot see much beyond the next quarter.

Ultimately, what matters is that at the end of the day, they make their destination, their NII and NIM, on time and as projected. Because those are their deliverables as far as their CFO is concerned. The good news is that they will make those projections, but the bad news is, or the reality is, that they are not magicians and cannot fix problems overnight. Because even if bank treasurers are neutral, they mean over time, not over the next second.

If tomorrow the Fed were to cut the Fed Funds rate by 300 basis points in one fell swoop, a change of that magnitude would cause some rocking somewhere on the boat, hopefully no worse than what metro New Yorkers felt during the highly unusual earthquake on April 5th. But give bank treasurers a quarter, six months, a year, or two years; they can adjust, restructure, and set up asset and liability cashflows to bring NII and NIM back in line with earnings projections.

And while bank treasurers usually seem like magicians, mistakes and the unexpected can happen. Look at what happened to Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) last year, which bank treasurers insist was a unicorn, and they would not have taken the risk there. But was it such a unicorn?

If other banks were so innovative not to buy bonds when interest rates were at all-time lows, how come at year-end 2023, the negative fair value mark on the banking industry's total investment portfolio, including bonds in HTM and AFS, equaled 18% of tangible common equity adjusted for taxes? Some banks or banks must have bought MBS and other long-term bonds, which, if sold today, would generate a realized loss of quite some magnitude and wipe out earnings. According to the Q4 2023 call reports, only 374 commercial banks out of 4,585 held securities in HTM and AFS with no fair value loss.

Of course, there was a time when buying bonds seemed like a wise trade.

Let's roll the tape back for a whole minute. Consider the following circumstances. The time is five years ago, April 2019. What would you have done? The FOMC had been on pause for two meetings, and the forwards were flashing that the Fed would cut rates before the end of the year, maybe once or even twice. Bank deposits exceeded total loans by $3 trillion, which today seems tame considering that deposits exceed loans by $5 trillion. But on a $18 trillion balance sheet back then compared to the $24 trillion balance sheet that prevails today, it was a lot of money to have sitting around at the Fed earning 2.4% (which the Fed was about to lower to 2.35%), when say, MBS was yielding close to 4%. Playing it safe in cash five years ago was not precisely accretive to NIM.

And lest you forget, assuming you matched the FDIC industry average, your bank's NIM peaked in Q4 2018 at 3.48%, and you had also booked a record NII. However, in the new year, the numbers for Q1 2019 were coming in lower, and Q2 2019's projections did not look any better, which certainly would not have made your CFO very happy. Your entire thought as bank treasurer was to protect NIM and NII, if not your career, to shield the public from the ugly truth that, as an asset-sensitive bank, you do less well when rates are falling than when they are rising.

There was talk of a recession, how it was overdue, and that recessions were inevitable. Then, like now! That meant probably credit losses were coming, which would have meant that your CFO would have been looking for the treasury to pump out more interest income from the bond portfolio to help cover the credit tab. You would have been feeling the pressure. And if you had any doubt about how the winds were shifting and the picture changing, you could have looked to the inverted 2s-10s yield curve for confirmation that who knows what kind of a recession, probably mild, was coming. An inverted yield curve often implies that rate cuts are coming, maybe even more than the forwards expected.

And you had to consider what would happen with your deposits, which had to go somewhere if they were not going to fund loan growth during a recession. And in recessions, people spend less money, which means they will save more, which means you will have more cash to invest. Everything cannot stay at the Fed overnight; be risk-free. What do you do when the excess deposit pile starts to grow? That would not help the NIM. The mounting pressure to keep NII and NIM on track was palpable in the conference room off to the side by the elevator in the treasury department, where bank treasurers huddled with their assistant treasurers, chief investment officers, funding officers, and ALM heads.

Bank Treasury 101 says in such circumstances, you buy bonds because that is what all good fixed-income investors are supposed to do when the Fed starts to cut interest rates. That is the best time to buy bonds. The best time to not buy bonds is when the Fed is about to raise rates, as was the case three years later in 2022, but in April 2019, like today, the Fed finished hiking rate hikes, and its subsequent move was a cut.

Meanwhile, your balance sheet was becoming more asset-sensitive, which increased your IRR if rates fell and added to the pressure you would have felt to act. You were becoming more asset-sensitive because your depositors were sitting on their cash, leaving more of it in non-maturity deposits than they had ever left in those accounts in modern banking history, earning just a couple of basis points. Meanwhile, more and more of your earning assets are at the Fed or in short-term bonds, earning a pittance.

Today, the situation is different. The only people who still want to sit in cash are bank treasurers because even though they are not crazy about the strategy, they cannot ignore TINA. There is no alternative. However, aside from these, other corporate treasurers are more careful about the cash they leave in their checks. And so are consumers, who are reportedly still looking to lock up their money in CDs. As the CFO from one of the global banks told analysts,

“Migration from checking and savings to CDs is sort of the dominant trend that is driving the increase in weighted average rate paid in the consumer deposit franchise. That continues…There's aa narrative out there about how we are seeing the end of what people sometimes refer to as cash-sorting. We've looked at that data. We see some evidence that maybe it's slowing a little bit…We don't think it makes sense to assume that we are in a world where checking and savings is paying 0% and the policy rate is above 5%, that you're not going to see ongoing migration.”

In April 2019, noninterest-bearing deposits equaled 24% of total deposits, well above the historical industry average (today, the ratio stands at 22%). And so, if you were the bank treasurer back then, you had a choice. You could have stood by and watched your NIM narrow, and your NII growth flatten, or you could have stopped being afraid, gone out, taken some IRR, and tried to earn some money for shareholders.

Many brave treasurers ventured out on the maturity spectrum, which at first went well and looked prudent, significantly as the Fed cut the rate three times in the second half of the year to 0% by March 2020. Speaking in the fall of 2019, after the FOMC had already cut the target range twice by 25 basis points, once in July and again in September, to 1.50-1.75%, the senior officer from one of the FHLBs observed in a note to members,

“In the post-crisis operating environment, many members have become asset sensitive with an expectation of rising rates while accepting substantial exposure to declining rates. In the recent declining-rate environment, those asset-sensitive members may be experiencing significant NII deterioration. Having a more neutral ALM position can assist with managing IRR and maximizing income across various interest rate environments.”

Bank treasurers could use FHLB advances to help manage this sensitivity, as the officer continued,

“Taking a “bet” on the direction of interest rates is admittedly risky and can expose you to greater risks, leading to lost earnings opportunities. Depending on the area of exposure, asset-sensitive members may want to consider shortening liabilities or adding long-term assets to become better match funded, whereas liability-sensitive members may want to consider taking advantage of points on the inverted advance curve to add term funding at advantageous levels.”

Adding long-term assets was one of several strategies bank treasurers pursued that year to protect their NIMs and NIIs. Later in 2020, when rates were back to the zero lower bound, and the subject of negative interest rates was being seriously debated among Fed economists when deposits by then exceeded loans by over $7 trillion, and when noninterest-bearing deposits exceeded 30% of total deposits making bank balance sheets even more asset sensitive than they were back in April 2019, when all that was going on, buying bonds was not only defensible, it was downright prudent, even if in hindsight, it turned out all wrong.

But for the record, to be fair, it was not a great time to buy bonds then as now, for many reasons, starting with the fundamental one, which is that term extension trades are upside down when the yield curve is inverted. In nominal terms, at least, the extension leaves the investor with a lower initial yield, which he can only recoup if the Fed cuts rates enough to make the initial give-up worth the investment.

When the spread between 3-month and 5-year Treasurys was 120-130 basis points last month, to extend required the Fed to cut rates aggressively for the extender to profit from this strategy. The investor would have to believe that a harder-than-expected landing was coming to buy into it. Even this month, with the spread falling to 60-70 basis points, the give-up seems too aggressive given the continued strength of the U.S. economy.

On top of that seemingly straightforward problem they would have had with the trade, in April 2019, fixed-income investors would have incurred a negative term premium (Figure 1) to extend the duration.

Figure 1: Term Premium on a 5 and 10 Year 0-Coupon Bond

If, for example, you had invested in a 0-coupon Treasury bond for five years because you believed the Fed would be cutting rates. By purchasing bonds, you wanted to protect the bank’s NII when rates were lower. When rates are higher, the market would have charged you a negative term premium for the extension, which ordinarily should be favorable to compensate an investor for taking on extension risk. Going further out the curve five years ago would have cost the same, but one year later, when hostile interest rate policy was in vogue, extending five more years to 10 years would have cost you an even higher negative term premium.

The term premium can be confusing as a buy, sell, or hold signal. In March 2022, extension risk would have paid investors a premium, even if it was insufficient to compensate for the unrealized loss they would suffer a year later. On the one hand, a positive term premium could have been interpreted as a sell signal, telling you that rates were likely to increase, not decrease. On the other hand, it might have been a buy or hold signal, paying investors instead of charging them to assume or hang on to extension risk. If it had been paying attention to term premia, SVB may have interpreted it as a buy signal, which it would have discovered was false.

Bank treasurers say they are considering extension trades again, inverted yield curve and term premium confusions aside, as the CFO from a global bank told analysts,

“We've started to do that to some degree in the first quarter, to buy some securities, mainly mortgages, given where rates and levels have been. And that's been a good trade, I think, for us so far. I think you'll see us continue to deploy more cash into securities, at least at some modest level, as we look forward over the next quarter.”

The CFO from a large regional bank in the northeast went into more detail on the bank’s purchases of securities in Q1 2024, telling analysts,

“We are trying to keep our convexity flat…purchasing Treasuries and CMBS, which basically has positive convexity, coupled with some low convexity MBS…The yields have been around 4.6% with duration at about a little over 3 years.”

Today, the Fed is officially on the verge of cutting interest rates, though “verge” might be too aggressive considering the latest spate of economic data. But assuming the Fed is done raising rates for this cycle and ignoring the term structure fundamentals, bank treasurers could be forgiven for once again giving some consideration to an extension trade for their $5 trillion in excess deposits. Even if they are not seriously worried about the Fed suddenly cutting rates by 300 basis points, it is reasonable to assume that interest rates are headed lower, if not this year, then next year.

Why? The Fed views a Fed Funds target range holding at 5.25%-5.50% as restrictive, and therefore, at some point, it will ease until it is satisfied that interest rates are at a neutral level. The economy is going gangbusters, and for now, at least, the present level of rates is not hurting it. Retail sales were fabulous last month. However, the Fed must cut regardless because a permanently restrictive monetary policy is not an economic policy at all, and if nothing else, leaving rates at these levels leaves the Fed less room to raise rates for the next time.

Presumably, if 0.00%-0.25% is too accommodative and 5.25%-5.50% is too restrictive, it is not unreasonable to believe that neutral is in the middle. But where exactly is neutral? The Fed thinks it will know it when it sees it. But how do you find it and see it?

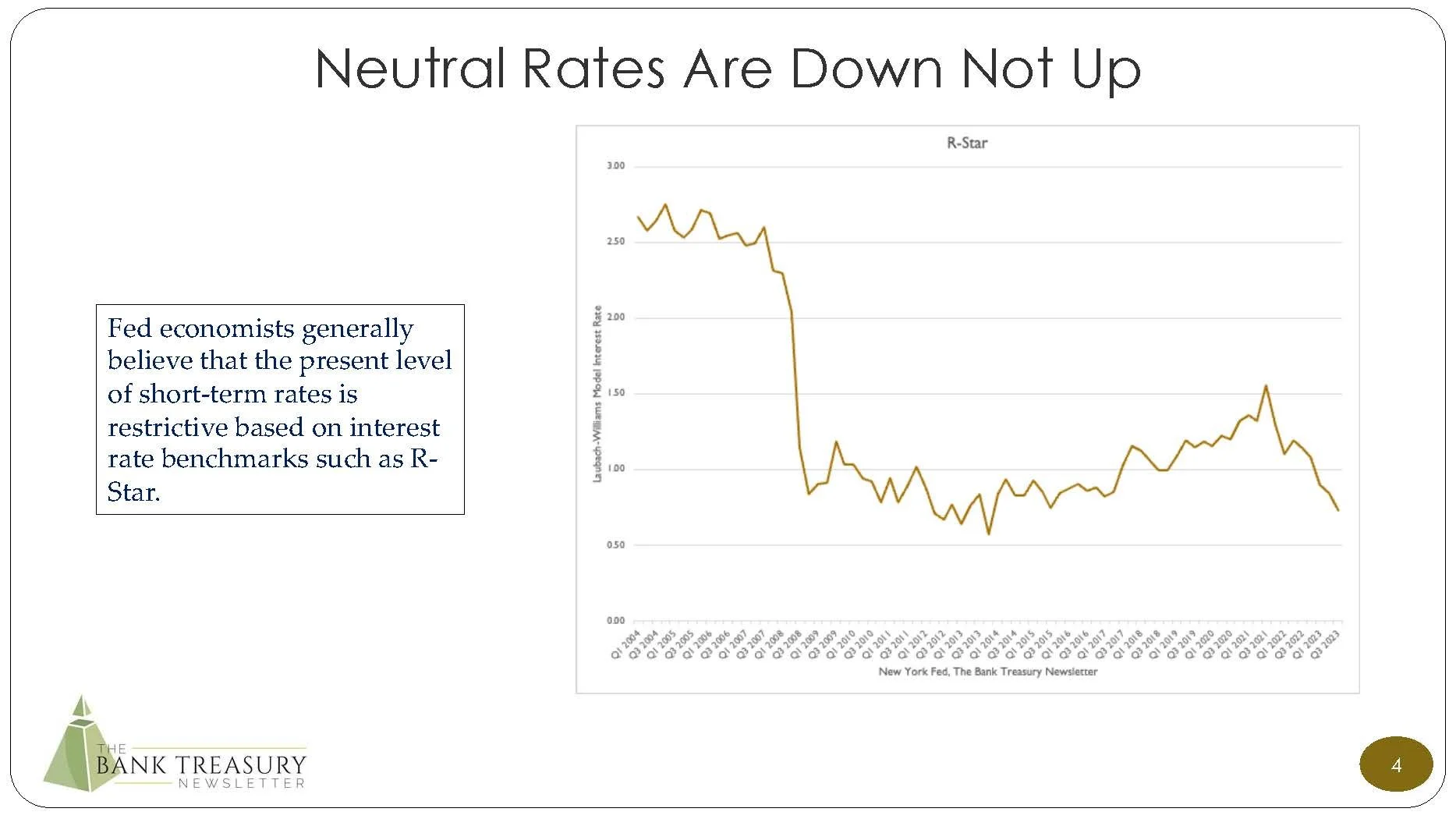

Without a roadmap like the one to find Gravity Hill, members of the FOMC look to R-Star, a hypothetical, cannot be directly observed, risk-free, overnight interest rate that is neither restrictive nor expansionary for an economy that is at full employment. R-Star represents a magic equilibrium between supply and demand for money, which moves around over time, higher and lower. Some economists believe it is higher today than in April 2019, and others think it is unchanged.

But what if R-Star is just an illusion? Maybe no equilibrium price for money clears the market? A New York Fed economist wrote a paper published last month that makes this very point: assuming an equilibrium in systems leads to a lot of model error. How else can we explain why, after holding the Fed funds rate for nine months and counting at its highest level in decades, the economy remains unbowed, and inflation remains stubbornly above 2%? Doesn’t the term “lag effect” mean anything these days?

What if the level of interest rates does not matter as much in 2024, and what if there is no equilibrium rate? R-Star is just an illusion, a trick of the lights, maybe. Maybe cutting rates will not be any more inflationary than raising rates has proved to be disinflationary.

One reason to be agnostic about the existence of R-Star is that the capital markets are very different today from those in previous credit cycles. Today, unregulated shadow banks, driven by private credit providers, are expanding their participation in the capital markets at the expense of the banking industry. Bank treasurers complain about this all the time, about the level playing field, and how the Basel 3 Endgame and regulatory regimes like it are ruining it for banks to participate in the capital markets the way they once were able to do.

The shadow banks may be bad for traditional banks. Still, from a public policy perspective, it may not be a bad outcome if we want to reduce the likelihood of a run on the financial system and avoid credit crunches that can exacerbate a downturn in the economy. Banks are usually the first ones out the door at the smell of smoke. But in a backseat position, with the shadow banks and foreign banks owning all that leveraged debt with sketchy outlooks, as credit losses mount per the Fed’s latest Shared National Credit exam, the run could end up a nothingburger despite all the handwringing about corporate bankruptcies and troubled office commercial real estate. The new players on the block may stick around longer and not run.

Private debt providers, especially those that are unleveled, will be less concerned with the level of interest rates as long they can earn a return for their investors, making the financial system far more stable than it was in previous economic cycles. The downside is that if private credit providers pull back from the capital markets, from leveraged loans, commercial real estate, and consumer savings and credit, the blowback to the rest of the economy and, indirectly, the banking industry could be significant. The pullback may already be happening, the chairman and CEO of a large asset manager observed,

“The large pension funds that have an overallocation of private equity and the rotation of money in the private equity area has slowed down precipitously. We are also seeing evidence that more and more clients are keeping a higher balance of cash to meet their liability discharges. And so, without the momentum and the velocity of money in private equity, they must keep higher cash balances, too.”

Corporate treasurers are sitting on more cash even if they are more selective about where they keep it, according to the CFO of global custodian,

“As the conditions in the economy continue to evolve, clients are holding more cash on their balance sheets.”

Thanks to competition from the shadow banks, high interest rates, and general economic uncertainty, loans are growing slowly on bank balance sheets while deposits have stabilized and now are trending higher. As the CFO from the global custodian bank continued,

“There does tend to be somewhat higher deposits in the banking system. So, the tide has been gently rising. I'd say very gently.”

And loan growth is slower, according to the CFO from a global bank,

“What we're hearing from clients in the commercial bank or some of the clients in the corporate investment bank, they're looking -- they're being cautious still and saying, "Okay, I'm not going to build inventories as much as I might in a different environment."

But back to the $5 trillion in excess deposits that bank treasurers need to invest, of which they have put $3.6 trillion in a Fed reserve account earning 5.4% overnight. Asset sensitivity is increasing again, and it could be fair to conclude, as bank treasurers concluded five years ago, that they and the financial markets are swimming in liquidity.

Except that liquidity is a mirage. Like neutral interest rate sensitivity and neutral interest rates, it does not exist, or at least it is fleeting and unreliable at best. One minute, there is plenty of liquidity in the financial system, everything is fine, and then it all goes POOF!

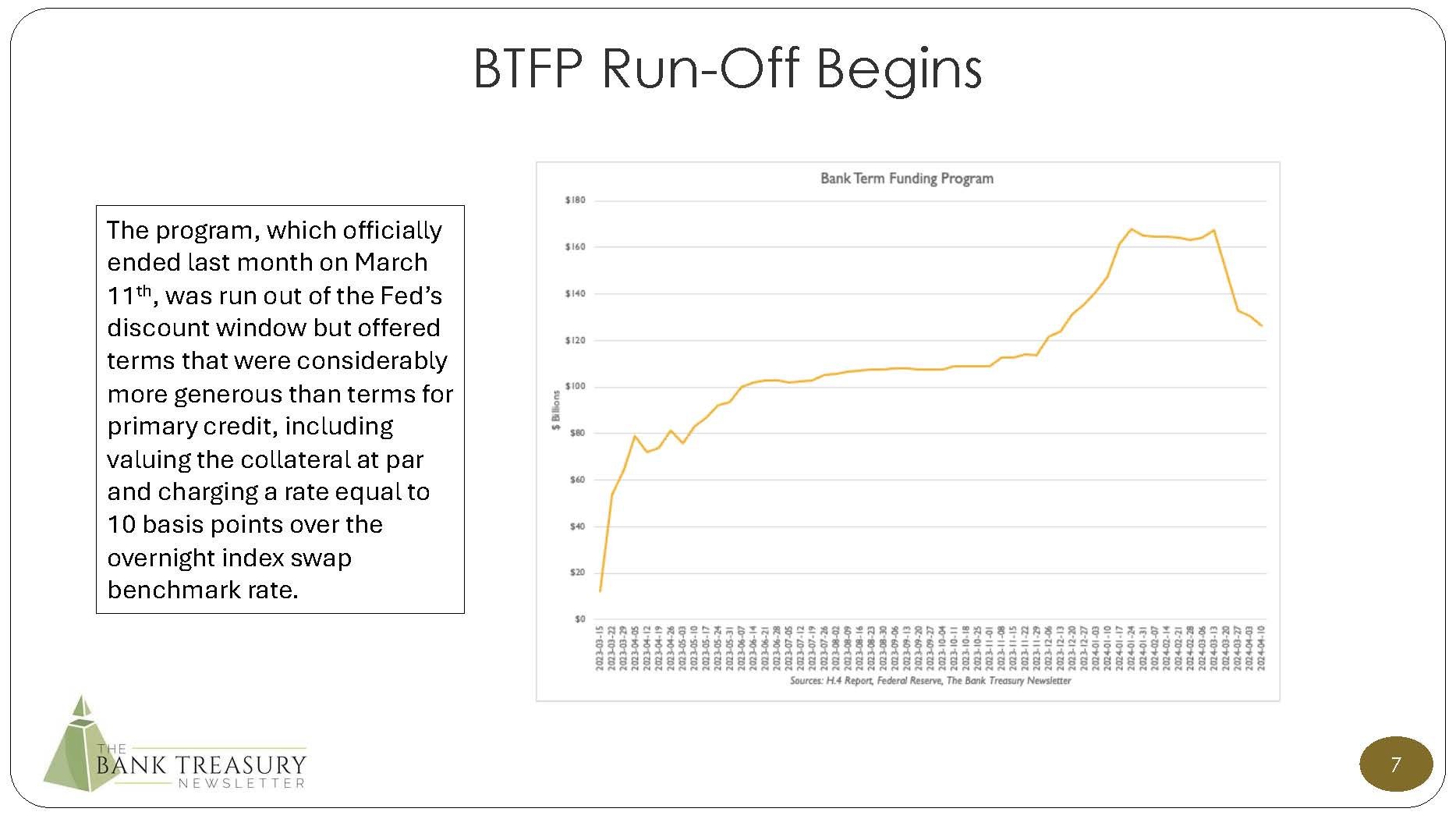

On September 15, 2019, there was suddenly no liquidity in the repo markets. The Fed had to pump in reserves, buy T-Bills for its SOMA portfolio, and even cut interest rates twice before the end of 2019 to restore market liquidity. And just a few months later, you had COVID-19 and the lockdowns, and again, liquidity just dried up in a flash. The Fed again had to move heaven and earth, with exceptional facilities and another dose of Quantitative Easing in the trillions of dollars, to the right markets. And finally, there was the crisis in March 2023, which led to the creation of the Bank Term Funding Program.

So, to say that markets are liquid today still begs the question: where does all the liquidity go when it disappears? Because most of what is called liquidity is not hard cash. There is no hard cash, currency, stacks of $100 bills, or piles of coins to point to and say, here is the liquidity.

Liquidity does not exist. It is just an accounting entry on the Fed’s balance sheet that echoes on bank balance sheets and the balance sheets of other financial participants in the capital markets. Thus, since last summer, as it continued to shrink SOMA by another $1 trillion, the Fed kept its reserve account flat and instead reduced the RRP from $1.3 trillion to $0.4 trillion. Shrinking the RRP meant that money market funds had to go back into bank deposits, which, at higher rates, these banks are only too happy to take back with open arms. As the CFO from a global custodian bank explained, deposits are moving higher despite QT because,

“We think that's a mix of central bank actions. In the U.S., the reduction in the overnight repo operation that the Fed's running. That comes back in a way into our clients or into the banking system, and that's been -- I think that's generally improved liquidity conditions or added to what is -- our very liquid conditions have made them even more liquid.”

But where is the money? Deposits are not sitting somewhere gathering dust in a bank vault. President Franklin Roosevelt explained this to the American people huddled around their vintage Phillips radios when he delivered one of his fireside chats in 1933. Explaining why he had closed all the banks for a bank holiday, which was to prevent a broader run on the financial system,

“First of all, let me state the simple fact that when you deposit money in a bank the bank does not put the money into a safe deposit vault. It invests your money in many different forms of credit—bonds, commercial paper, mortgages, and many other kinds of loans. In other words, the bank puts your money to work to keep the wheels of industry and of agriculture turning around. A comparatively small part of the money you put into the bank is kept in currency—an amount which in normal times is wholly sufficient to cover the cash needs of the average citizen. In other words, the total amount of all the currency in the country is only a small fraction of the total deposits in…the banks.”

When FDR spoke to the nation to explain how banks work, currency in circulation equaled $5 billion and deposits for commercial and savings banks equaled $27 billion. Today those numbers are $2.3 trillion and $18.0 trillion, respectively. Yet, currency in circulation remains roughly the same fraction of total deposits (Figure 2). If all the deposits in the system had to be monetized overnight, it would require the Fed’s balance sheet to double in size to provide enough currency to meet the demand.

Figure 2: Currency in Circulation as % of Total Commercial Bank Deposits

Liquidity is not about hard cash. It is about trust. Your money is safe in the bank, like our currency, and is a statement of faith, like belief in God. Stop believing, and you can have a run. The establishment of the FDIC helped with that faith, but FDIC insurance did not stop withdrawals of large uninsured deposits from Washington Mutual during the Global Financial Crisis. Liquidity is an illusion, and like all illusions, it shatters quickly.

The Fed’s role as lender of last resort is supposed to bolster the public’s sense of security, which is a sore subject for bank supervisors, who are still smarting over the circumstances of SVB’s failure, how when it started seeing deposit outflows it went to its FHLB for a loan instead of the discount window. Critically, SVB had not prepared to use this resource when it failed. One of the lessons bank supervisors believe they have learned from the crisis last year was that this needs to change, that bank treasurers need to have the Fed’s discount window in their operational liquidity plans.

To that end, bank examiners guide banks in establishing pre-positioned collateral at the discount window to use in case of another liquidity crisis. Fed Governor Bowman this month summarized her concerns with this approach, speaking to a roundtable sponsored by the Committee on Capital Markets Regulation,

“One prominent issue that has come to light recently is whether there should be some form of pre-positioning requirement—whether banking institutions should be required to hold collateral at the discount window, in anticipation of the need for accessing discount window loans in the future.”

This could be a good idea, BUT as she continued,

“To fulfill its function, the discount window must be able to provide liquidity quickly. The failure of SVB demonstrated how rapidly a run can occur and revealed that the discount window must be able to operate in a world in which new technologies, rapid communications, and the growth of real-time payments may exacerbate the speed of a bank run.”

Good ideas do not come without a price. Even if the discount window were open 24x7, requiring bank treasurers to pre-position collateral at the discount window could be detrimental to profits and interfere with efficient ALM. Indeed, bank treasurers are already concerned that pledging collateral at the window could reduce the amount of collateral available to borrow from the FHLBs. And Governor Bowman asked,

“Would requiring pre-positioning of collateral impede a bank's ability to manage its day-to-day liquidity needs (including from private sources at lower cost)? Would pre-positioning collateral increase operational risk, or otherwise change bank activities? Would there be any unintended consequences from requiring banks to encumber more assets on their balance sheets? More fundamentally—is a change of this magnitude, requiring a new daily management of discount window lending capacity, necessary and appropriate for all institutions, or are there particular bank characteristics that may warrant this additional layer of liquidity support?”

Liquidity all comes down to trust, and to keep that trust from being shattered, FDR’s banking reforms established deposit insurance and reaffirmed the Fed’s role as lender of last resort. In addition, bank regulation and supervision help to anchor the public’s trust that the banking system is a safe place to put one’s trust, even if their money is not technically there. Unfortunately, bank regulation and supervision are not one united front because many Federal and state agencies share oversight for the U.S. banking system’s safety and soundness, who put out their regulations and communicate their guidance to the institutions they charter.

At the Federal level, there is the Fed, the OCC, and the FDIC; at the state level, there are 50 individual state banking departments. State banking departments supervise state-chartered banks, but all banks are supervised at the Federal level, with either the Fed, the OCC, or the FDIC serving as an institution’s lead examiner. The National Credit Union Administration (NCUA) supervises the credit unions separately.

Far from being a united front, this complicated web of bank supervisory agencies and departments compete with one another, for better or worse, for bank charters. Banks are known to shop regulators to find ones that will say yes, not no. Out-of-state bank mergers can add to one state banking department’s roster at the expense of another. Why is the system the way it is? The real reason is that this is how the banking system developed over 200 years. As a work in progress, the patchwork system with the banks was first regulated only at the state level. The OCC’s charter lasted until 1863, the Fed came in 19 when 14, and the FDIC came in 1933.

The system is known as the dual-banking system, where bankers answer to more than one regulator, both state and Federal examiners. Alan Greenspan believed in the dual banking system and that banks should be able to choose their regulator. Otherwise, an overly strict bank supervisor might prevent innovations that a different set of eyes would have green-lighted. That could be good, but it could also be bad. A paper by the Richmond Fed suggested that it depends. The IMF thought it was terrible. Other studies feel the same thing.

Generally, the public sees a united front in umbrella bank supervisory associations, such as the Federal Financial Institutions Examinations Council (FFIEC), which includes the Fed, the OCC, the FDIC, the NCUA, the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau, and the State Liaison Committee. This latter comprises representatives from the Conference of State Bank Supervisors, the American Council of State Savings Supervisors, and the National Association of State Credit Union Supervisors. Yet sometimes, the disunity among the various agencies is hard to hide from the public.

The OCC’s latest proposal on bank mergers is a case in point, which it published without the concurrence of the Fed and the other bank supervisors that make up the FFIEC. If the rule is adopted, which would seem as drafted to raise the bar to get approval for a bank merger, there is a risk that the other regulators may make different rules. As a partner at Davis Polk observed this month,

“I worry about individual federal banking agencies putting out individual policy statements [and] expressing their own individual agency views on statutory standards instead of developing an interagency approach.”

Sometimes the dual banking system can get in the way of effective bank supervision. As the Fed found during its review of SVB, the supervisory system can be inefficient in communicating to banks when it is critical,

“The memorandum of understanding was still in draft form and was in process of being submitted to the California Department of Financial Protection and Innovation (CDFPI) for another round of review when SVB failed. The MOU drafting process involves stakeholders across all agencies, including Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, Board Supervision and Regulation, Board Legal, and CDFPI, and can be time consuming to complete.”

Neutral balance sheets and neutral interest rates, the appearance of liquidity in the financial system, and the expectation that bank regulation and supervision will be up to the task during flash liquidity crises that bring down investment-grade banks overnight or over weekends, all these things may be an illusion. But some things are real. When you finish at Gravity Hill, return to Bedford on SR 220, and stop at the Route 220 diner, where breakfast is served all day. The cook in the kitchen in the backroom is said to be a wizard with Belgian waffles.

The Bank Treasury Newsletter is an independent publication that welcomes comments, suggestions, and constructive criticisms from our readers in lieu of payment. Please refer this letter to members of your staff or your peers who would benefit from receiving it, and if you haven’t yet, subscribe here.

Copyright 2024, The Bank Treasury Newsletter, All Rights Reserved.

Ethan M. Heisler, CFA

Editor-in-Chief

In This Month’s Chart Deck

Following up on the themes in this month's newsletter, the first set of slides illustrates some conflicting trends related to interest rates and the outlook for cuts by the Fed before the end of the year. For example, even though Fed officials seem to be backing away from initiating cuts before the summer, they are still institutionally committed to cutting the Fed funds rate because they view it as restrictive. Their views are guided in part by the theoretical interest rate called R-Star, which is an equilibrium risk-free, overnight rate, which is not expansionary or restrictive assuming that the economy is at full employment, and which, as shown in Slide 4, remains relatively unchanged since the Global Financial Crisis when the Fed brought rates down to the 0 lower-bound. Nevertheless, the market continues to fade rate cuts in 2024 based on what the forwards and Fed fund futures indicate (Slide 5). As the inverted yield curve reverts and 10-year Treasury yields climb above 4.6%, the fair value unrealized loss in bank investment portfolios is unlikely to recover soon (Slide 6).

Last month, the Fed ended its special liquidity facility, the Bank Term Funding Program (BTFP), which peaked at over $160 billion. Since it was closed, the facility's balance, which consists of one-year loans that banks could use to fund their bond portfolios at their par value at what was then a generous rate, is already down by $30 billion (Slide 7). Sitting on the asset side of the Fed's balance sheet, the falling BTFP also reduces bank reserve deposits on the liability side of its balance sheet. However, as Slide 8 traces, the Fed is also working down the balance of its Reverse Repo Facility (RRP), which, because it sits on the liability side of its balance sheet, counteracts the effects of Quantitative Tightening (QT) and the falling balance of the BTFP, and was the primary reason why bank reserve deposits at the Fed have been increasing (Slide 9).

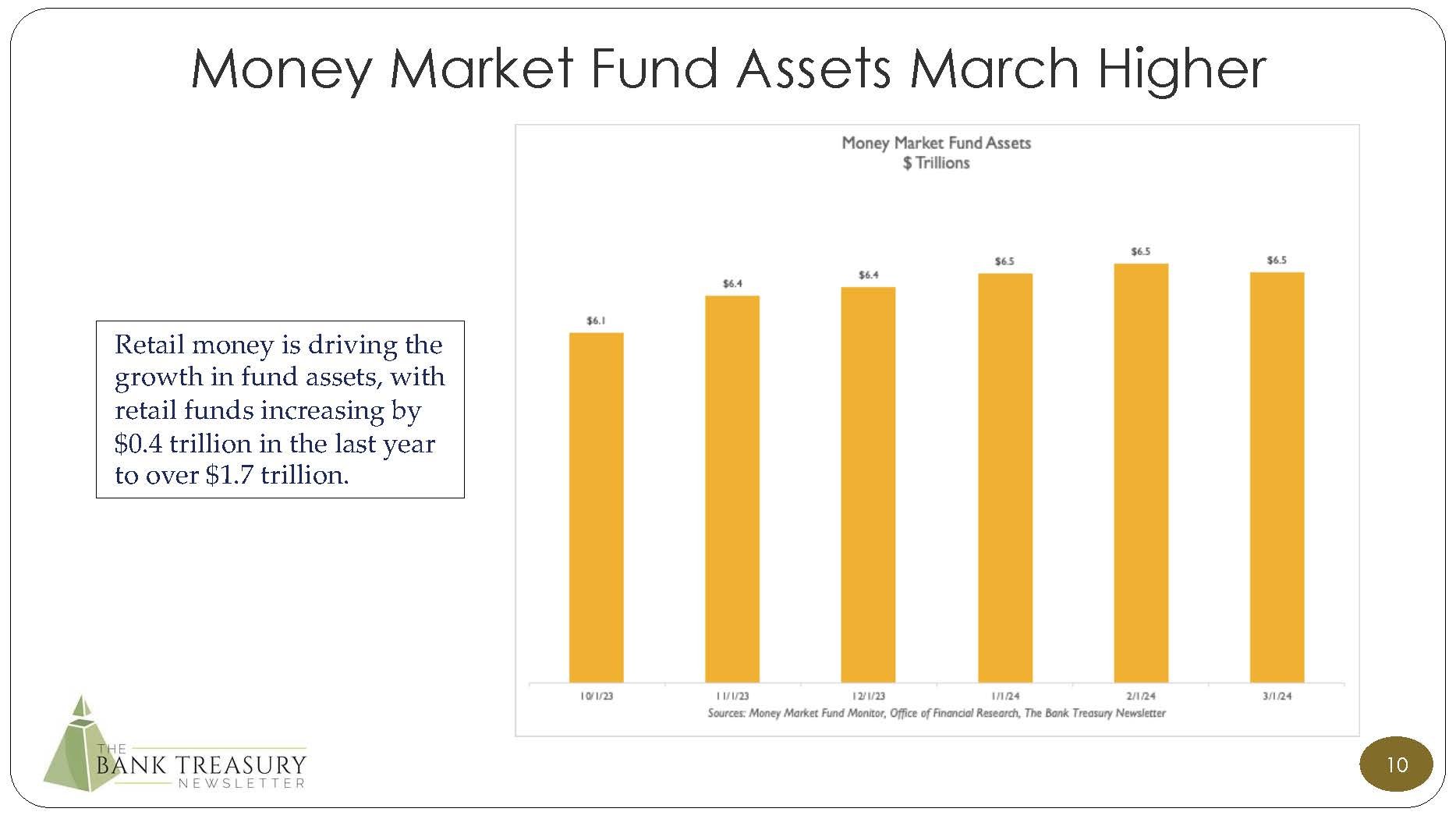

Squeezed out of the RRP, Money Market Fund assets, heading towards $7 trillion (Slide 10), have returned to bank deposits (Slide 11). Meanwhile, with loan demand slacking, given the uncertainty about the economy and the timing of rate cuts, banks in the Fed’s large bank peer group used in its H.8 report have deployed their excess deposits to increase the balance of their investment portfolios, primarily in Treasurys (Slide 12). However, banks also reported this month that they had begun to buy mortgage-backed securities (MBS).

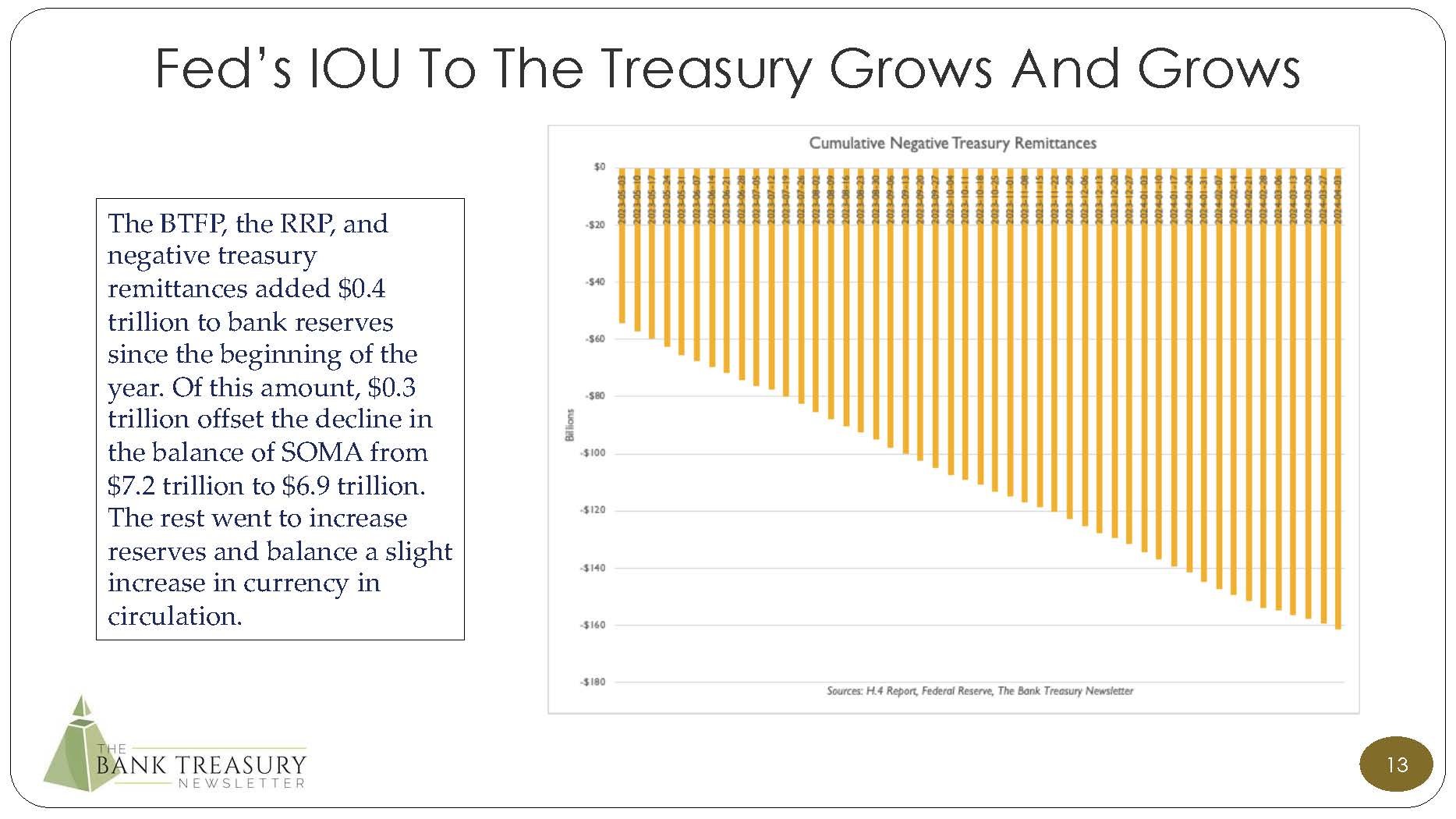

Earning roughly $45 billion a quarter on its System Open Market Account (SOMA) and its other interest-earning assets (based on its Q3 2023 statement), the Fed is paying out $73 billion to banks, money market funds, and other central banks in interest expense for reserve deposits and the RRP. The deficit is accumulating as an IOU to the U.S. Treasury (Slide 13) on the liability side of its balance sheet and equaled over $160 billion this month, which also adds to bank reserve deposits.

List of Slides

R-Star, Laubach-Williams Model, Sources: New York Fed, The Bank Treasury Newsletter

30-Day Fed Funds Futures, September 2024 Expiration, Sources: Barchart.com, The Bank Treasury Newsletter

Unrealized FV Loss In Total Securities (AFS + HTM), December 2023, Sources: Call Reports, FIS FedFis LLC., The Bank Treasury Newsletter

Bank Term Funding Program, Sources: H.4 Report, Federal Reserve, The Bank Treasury Newsletter

Reverse Repo Facility, Sources: H.4 Report, Federal Reserve, The Bank Treasury Newsletter

Reserve Deposits, Sources: H.4 Report, Federal Reserve, The Bank Treasury Newsletter

Money Market Fund Assets, Sources: Money Market Fund Monitor, Office of Financial Research, The Bank Treasury Newsletter

Bank Deposits, Sources: H.8 Report, Federal Reserve, The Bank Treasury Newsletter

Treasury and Agency MBS Held By Large Banks, Sources: H.8 Report, Federal Reserve, The Bank Treasury Newsletter

Cumulative Negative Treasury Remittances, Sources: H.4 Report, Federal Reserve, The Bank Treasury Newsletter