BANK TREASURERS WERE NOT ON THE MAYFLOWER

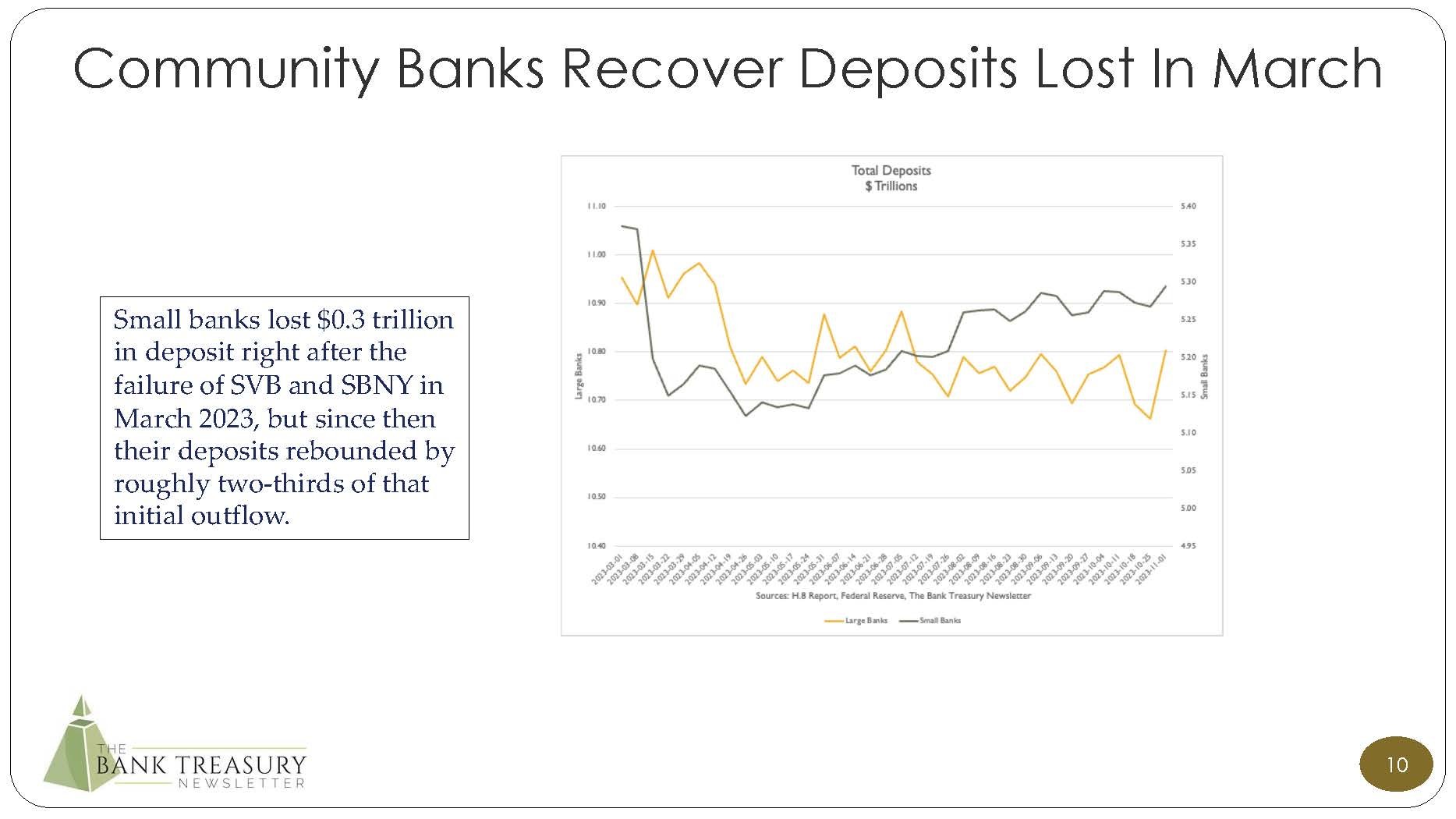

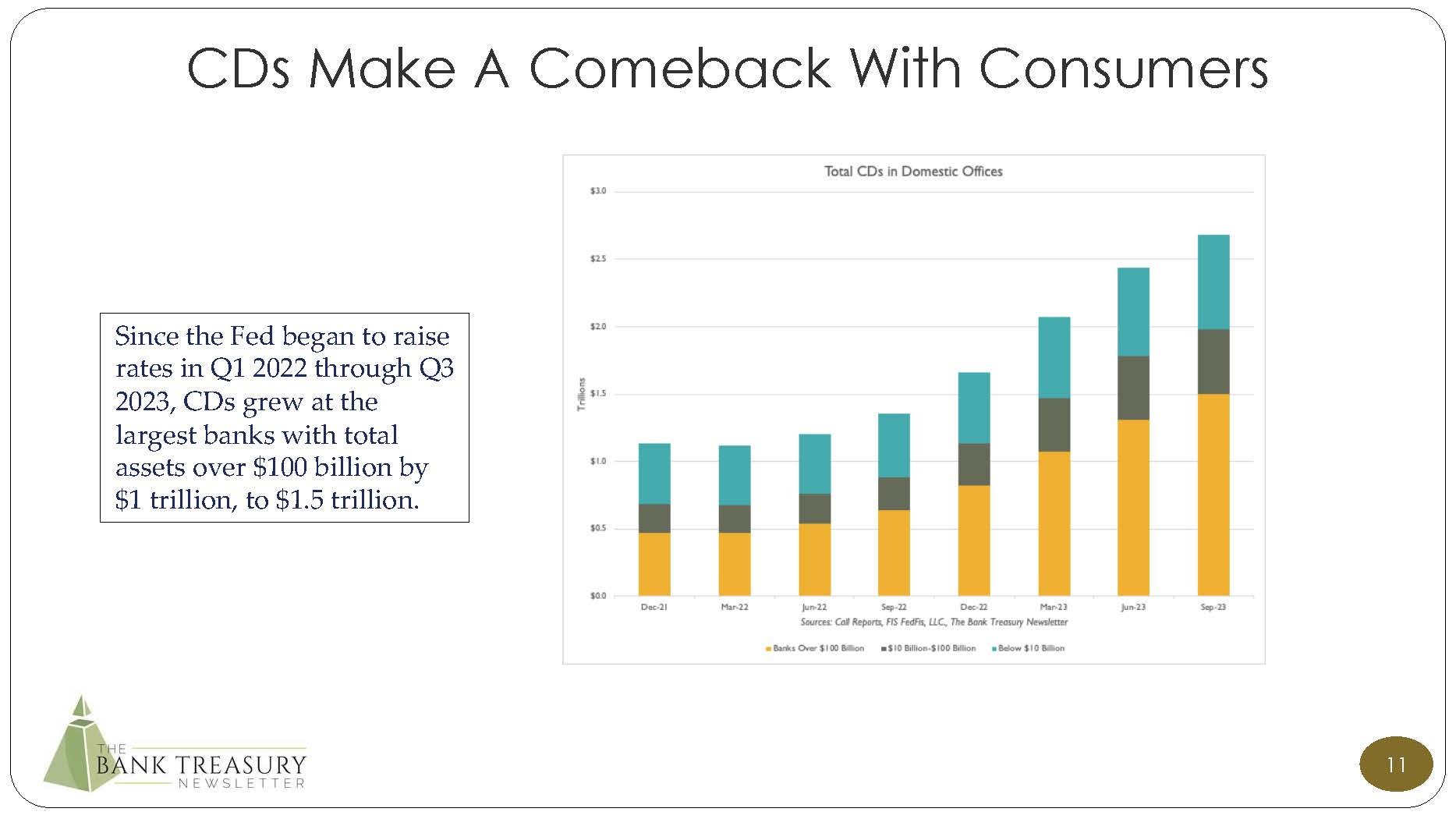

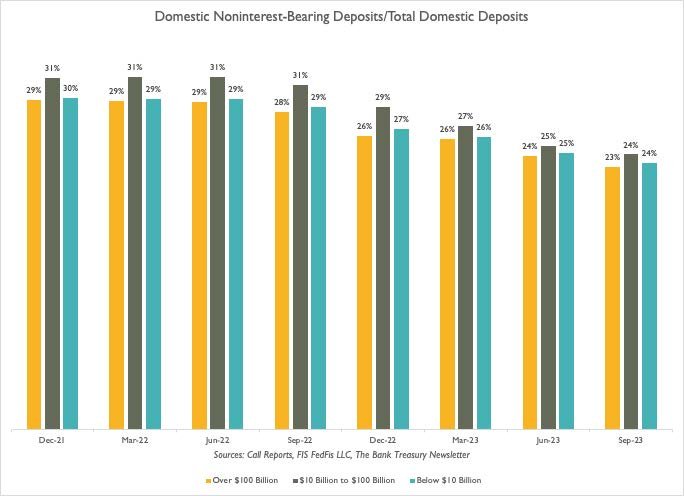

Bank treasurers report that deposit outflows since the failure of Silicon Valley Bank (SVB), Signature Bank, New York (SBNY), and First Republic Corporation (FRC) have stabilized and that the shift they had been seeing since Q3 2022 from noninterest-bearing deposits into interest bearing deposits is also starting to stabilize. However, in the consumer space they are continuing to see depositors shift into CDs (see Slide 12 in this month’s chart deck), which has been difficult to model because of the rapid increase in interest rates and is creating a headwind on their net interest margins (NIM). Banks are also refining their modeling technique for uninsured deposits as a key lesson learned from the bank failures last spring.

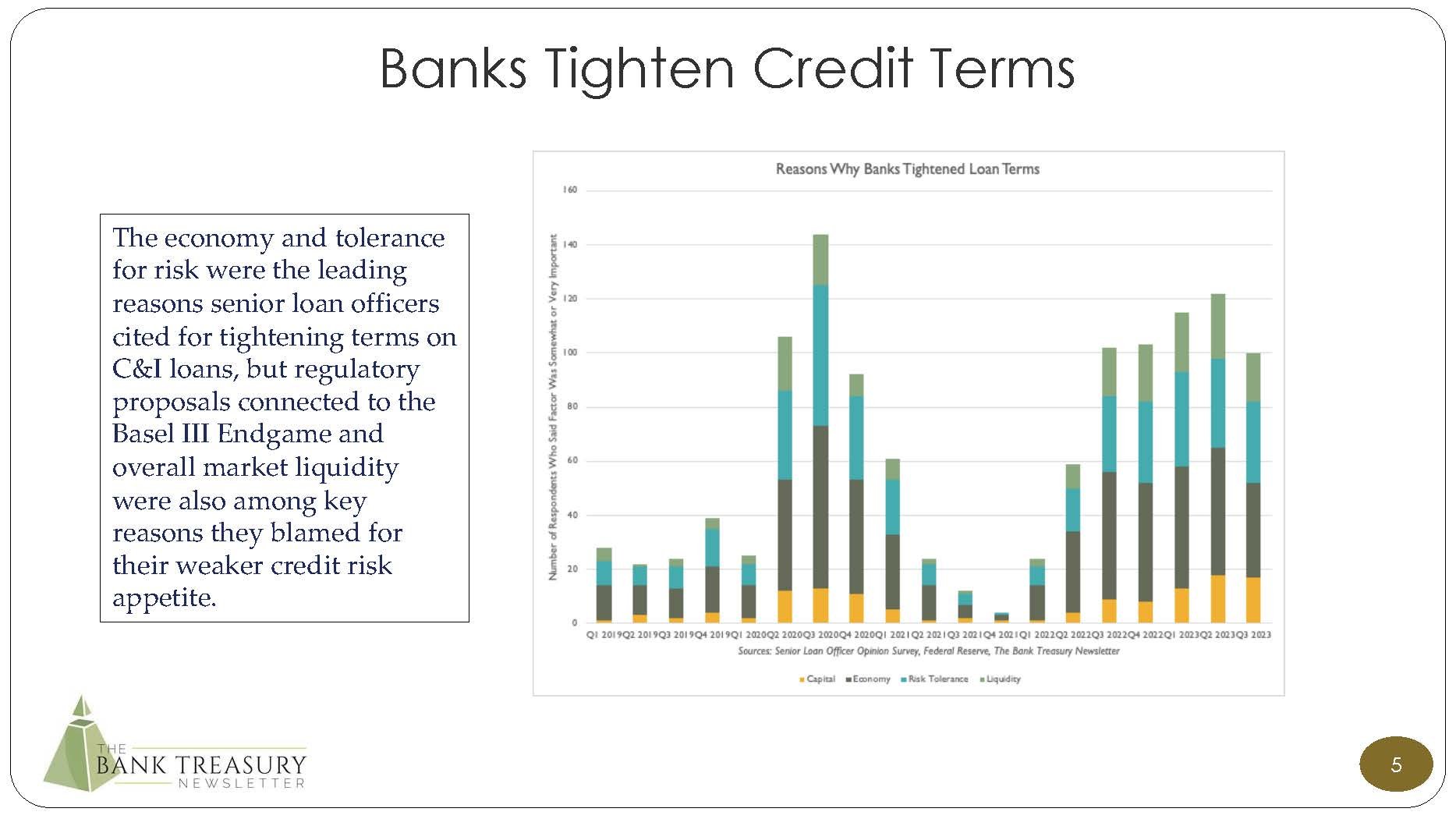

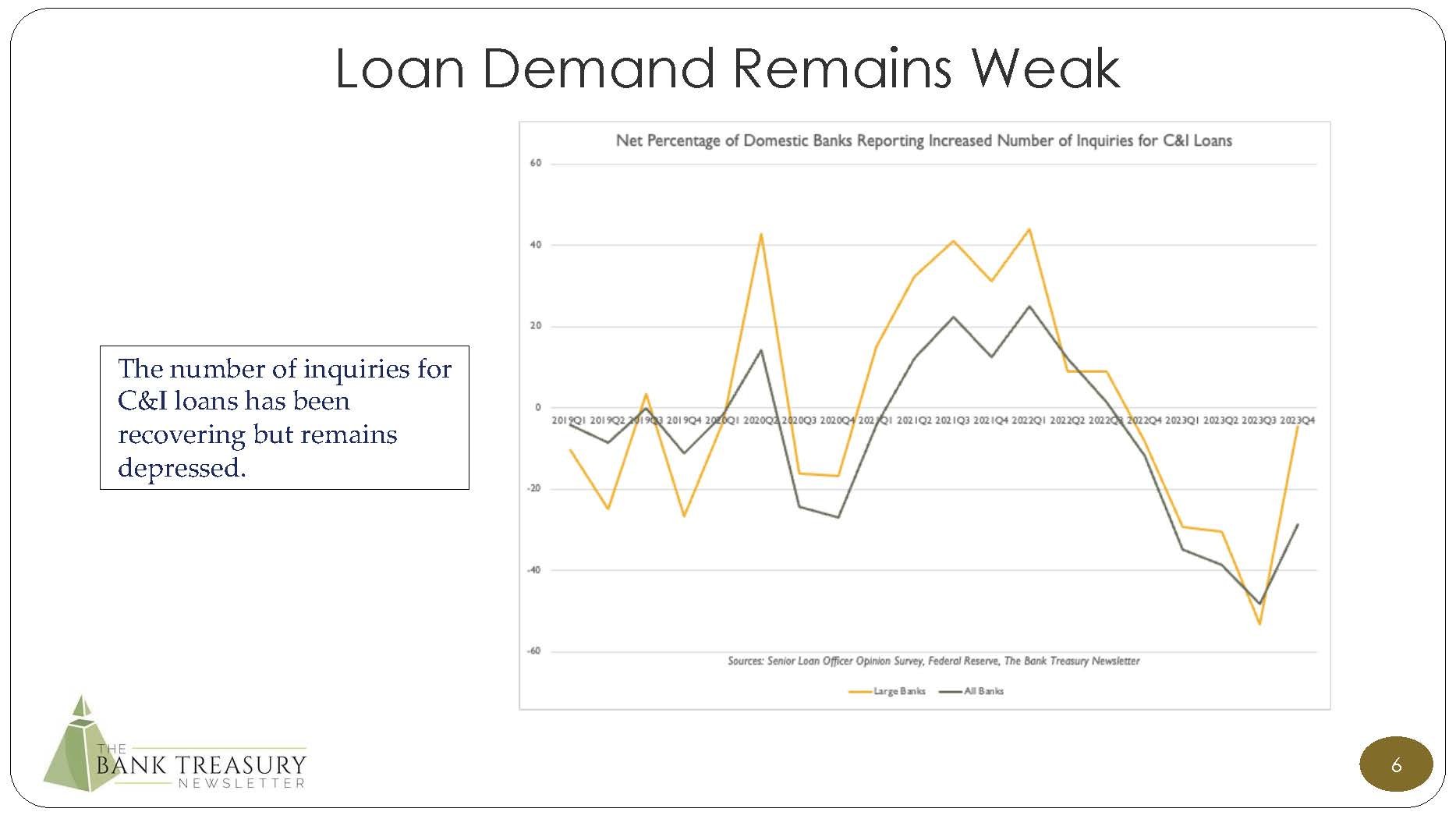

Loan growth is slowing which is reducing bank treasury appetite to pay up for deposit funding. Deposit markets for the most part remain a local story, depending on the ratio of loans to deposits as well as competition from credit unions, and nonbank players. Larger banks are also adopting risk-weighted asset (RWA) optimization diets, becoming more diligent in shedding lending relationships which do not meet return hurdles on their cost of capital. Some smaller banks have told the newsletter that they have picked up some of the loan business that their larger peers walked away from, but even at smaller banks, loan-to-deposit ratios have stabilized since the summer, some banks even expecting higher deposit growth than loan growth in Q4 2023. But banks are still sitting with more deposits than loans by a wide margin. According to H.8 data, the loan-to-deposit ratio for the Fed’s large bank and small bank peer groups was 63% and 84%, respectively this month, up from 60% and 80% just prior to the bank failures last March.

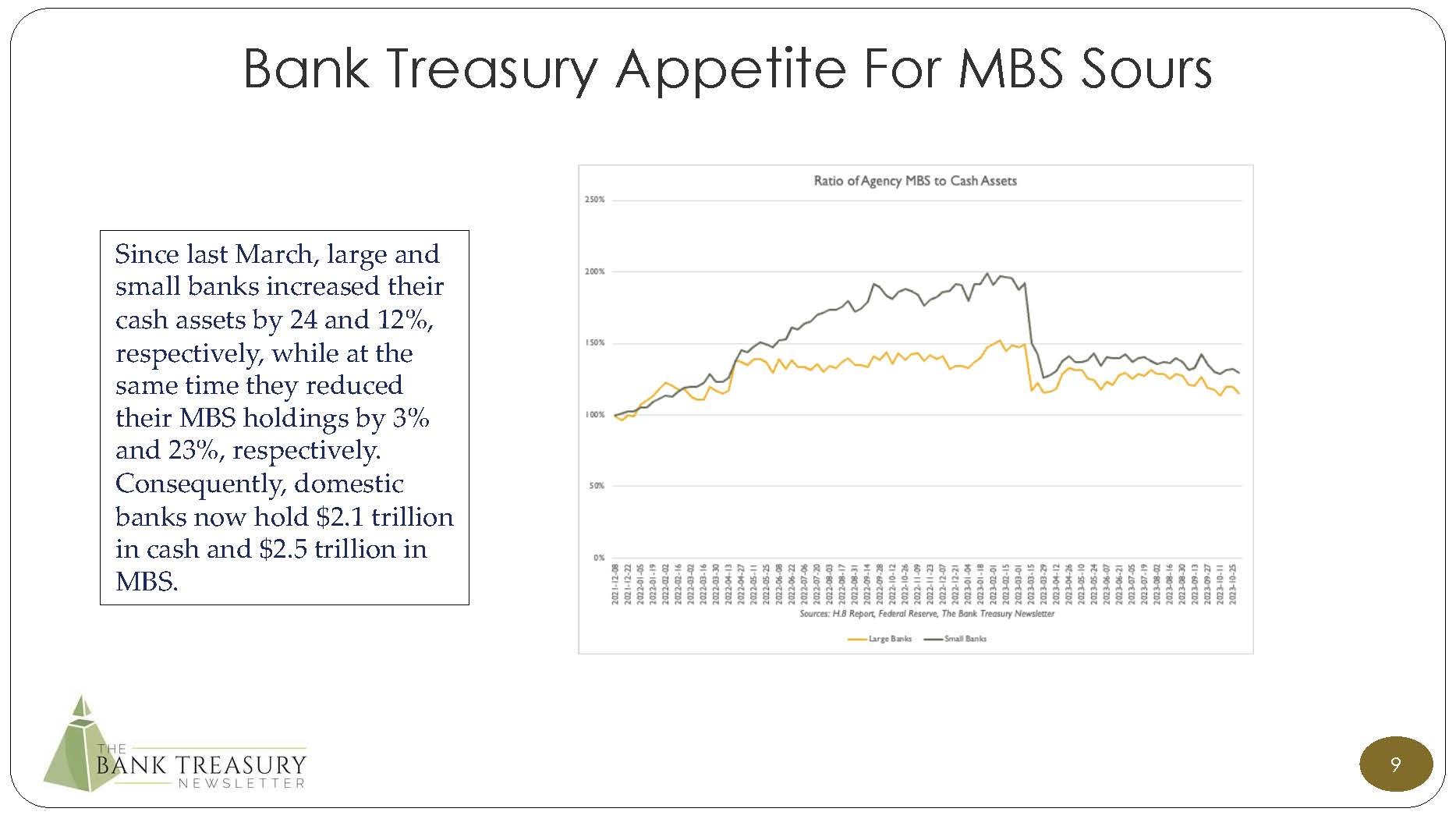

For the most part, even with the crisis having eased, bank treasurers of all sizes report less appetite for buying mortgage-backed securities (MBS), are modelling their deposits for shorter duration, and expect to hold more cash than they held before the crisis. Even though bond portfolios remain deeply underwater, which has complicated their balance sheet liquidity management planning, bank treasurers tell the newsletter that they continue to view this asset class primarily as a source of liquidity.

The Federal Housing Finance Administration (FHFA) published its long-awaited report this month, the FHLB100, where it outlined several rulemaking proposals that it expects to make in line with conclusions it has drawn from its six-month study that ended last March. Among the proposals, the FHFA wants to impose an on-going requirement that institutions have 10% of their assets concentrated in residential mortgage-related assets to be eligible for an advance. Broadly considered, based on current H.8 data, Agency MBS and residential mortgage loans equaled 26% of total assets for the large banks and was 23% for the small banks. However, based on Q3 2023 call report data, there were 700 institutions out of 4,600 commercial banks, including more than a dozen institutions with total assets over $10 billion, that would not have met this requirement as of the end of Q3 2023.

The FHFA was emphatic that the FHLBs are not a lender of last resort and are not established to provide an emergency loan to an institution that should be going to the Fed’s discount window, or the Bank Term Funding Program scheduled to expire next March. The FHLBs, for example, rely on their ability to access the debt capital markets to fund advances which are not open after business hours if an institution came to them in the middle for help. Among other proposals, the FHFA is considering mergers among the eleven FHLBs, but the report did not discuss expansion of membership eligibility to nonbank institutions that have come to dominate the residential mortgage space, including Quicken and Rocket Mortgage.

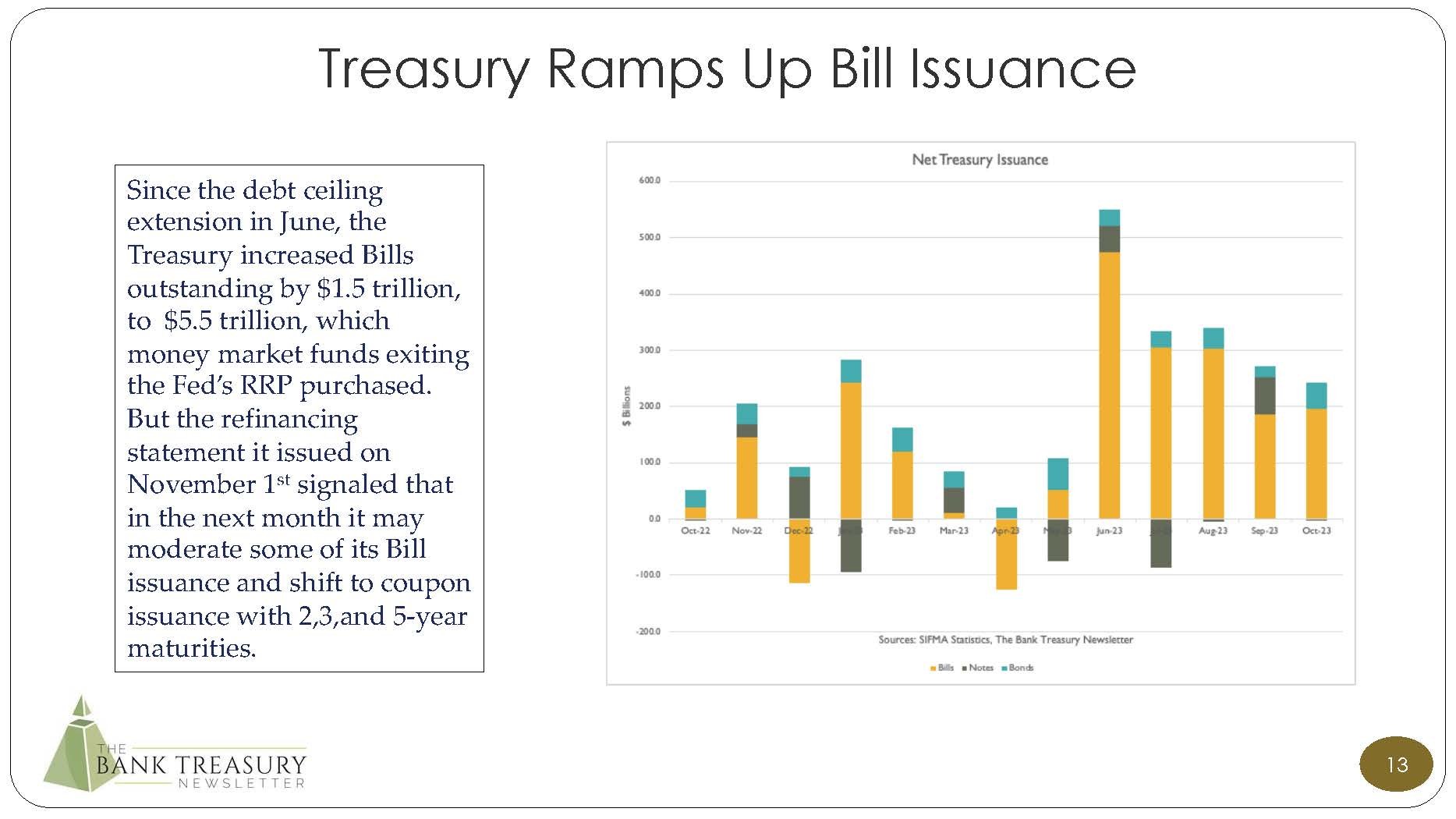

The Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) kept its rate on Interest on Reserve Balances (IORB) and the Reverse Repo facility (RRP) steady. Bank treasurers see the forward rates, hear the economic consensus, and generally believe the Fed will not raise rates further for this hiking cycle. Some are not so sure. Even with an inverted yield curve, bank treasurers are adding hedges to protect bond portfolios from higher rates but are just as worried about protecting earnings against lower rates.

The Bank Treasury Newsletter November 2023

Dear Bank Treasury Subscribers,

If there had been newspapers when the Pilgrims were making their crossing to their “strange and hard land” in 1620, the voyage of the Mayflower probably would not have been the leading contender for front-page, top fold, story of the day. It may not have gotten much coverage at all even though some historians would consider it to be a pivotal moment. Instead, an editor-in-chief then, much like one today, would have run stories focused on chaos, war, and destruction. Because as always, that is what gets eyeballs in the newspaper business.

And especially war because there was a lot of it going on back then. The Thirty Years War, for example, was then in its second year, raging across the European continent between the reforming Protestants and counter reforming Catholics. Think of Dartagnan and his merry band of musketeers who would have been contemporaries of the Pilgrims if not for the fact that they were fictional creations of a 19th century novelist. The Eighty Years War was also going strong between the overbearing Hapsburgs and the plucky Dutch masters who just wanted to be free like any other enterprising mercantilist to make money and smoke cigars. And some space would have been devoted to an update on the Polish-Ottoman war which had something to do with the prince of Transylvania’s campaign to assert control over Moldova, or something like that. Who remembers now?

The bottom of the fold might have been dedicated to stories on climate change, what with the world in the grip of a Little Ice Age. You could have shown pictures of starving babies and failed crops. Definite clickbait stuff. And everyone loved stories on witchcraft back then, what with the number of condemned prisoners burned at the stake reaching a high point just as the Pilgrims were sitting down for their first Thanksgiving meal. The celebrity witchcraft trial of Katherine Kepler, Johannes Kepler’s mom, the astronomer dude who discovered something about planetary orbits, was going on and would have been a lead story in the papers, if not for the fact that Queen Elizabeth I’s ban on them since 1586 was still in force. Where is social media when you need it?

But if there were newspapers, the financial section might have paid some attention to the Pilgrims because of their backing by the Merchant Adventurers, an influential private equity group known for their highly speculative financial adventures. The Mayflower was a moonshot, their investment was high risk, and so they expected unlimited optionality in return. The only game in town, take it or leave it, the Pilgrims took their sky-high terms including a six-day work week, a major concession on their part given that they wanted four-day work weeks and three-day weekends.

And the reason was that even if the Pilgrims were the safest investment, it was a lenders’ market back then. Rates were high at least relative to where rates are this month with the 10-Year Treasury yield down to 4.5%. Borrowers were desperate for liquidity and were likely to sell their soul for a loan. King James I, if he had had to borrow money, might have paid as much as 10% interest for the privilege.

The Pilgrims were also the least likely individuals anyone would have ever picked to run a start-up overseas colony given their utter lack of practical experience. The Pilgrims were tailors, hatmakers, glovers, shoemakers, carpenters, block and tackle makers, twine makers, leather workers, coopers, cabinetmakers, brewers, masons, watchmakers, mirror-makers, tobacco sellers, tobacco-pipe makers, midwives, and merchants. There were no bank treasurers on board, but then again there were no banks in England until 1694 when the Bank of England was established.

More importantly in the context of the colony’s prospects of surviving through a harsh New England winter in the middle of the Little Ice Age and ultimately in terms of return on investment, they were not farmers, fishermen, builders, soldiers, explorers, hunters, or anyone else one might normally think of as useful to colonize the new world. The Bradfords, Brewsters and all the rest of the Pilgrims that came on the Mayflower would have been eliminated on the TV show Survivor by the first episode if television had been around back then. Added to that, the odds of success were long.

Previous efforts to settle in the new world had been spectacular flops, the smoke that was still rising from the Jamestown massacre down south serving as the latest reminder to any would-be investor that beyond the short-term investment horizon there still be dragons.

But more than likely, most of the coverage in a newspaper’s financial section back then if there had been newspapers would have been devoted to stories about the Kipper und Wipperzeit financial crisis of 1619-1623, caused by the Holy Roman emperor who debased his currency to pay for the Thirty Years War. Kipper means to clip and Wipperzeit means to seesaw on a scale, which is exactly what happened. In a case of throwing good money after bad, the gold and silver coins of his realm were shaved, the shavings were collected and used to make other coins, and the remaining metal was melted down and mixed with lead and other base metals. After that, the adulterated, debased coins were returned to circulation. And that is why it was called Kipper and Wipperzeit.

It was crazy. Of course, the commoners had no idea what was going on. All they knew was that everything was going up in price and you could not trust that any coin coming from the Continent was worth anything. Everything was getting marked to market and oh boy, now you could see that some emperors were swimming naked.

Imagine the human-interest stories that would have run on how the price of eggs had increased fourfold over 100 years. Think of the Person-on-the-Street interviews that might have been done with the bucolic village peasants as they were going in and out of their local supermarkets, but for the fact that they had no supermarkets, expressing their disbelief and dismay over just how everything was just headed, who knows, don’t want to say it, but you know, headed for H-E-double toothpicks. Nothing was the way it was when they were growing up in the 1500s, when people paid the same price for stuff as their parents, grandparents, and generations before them did.

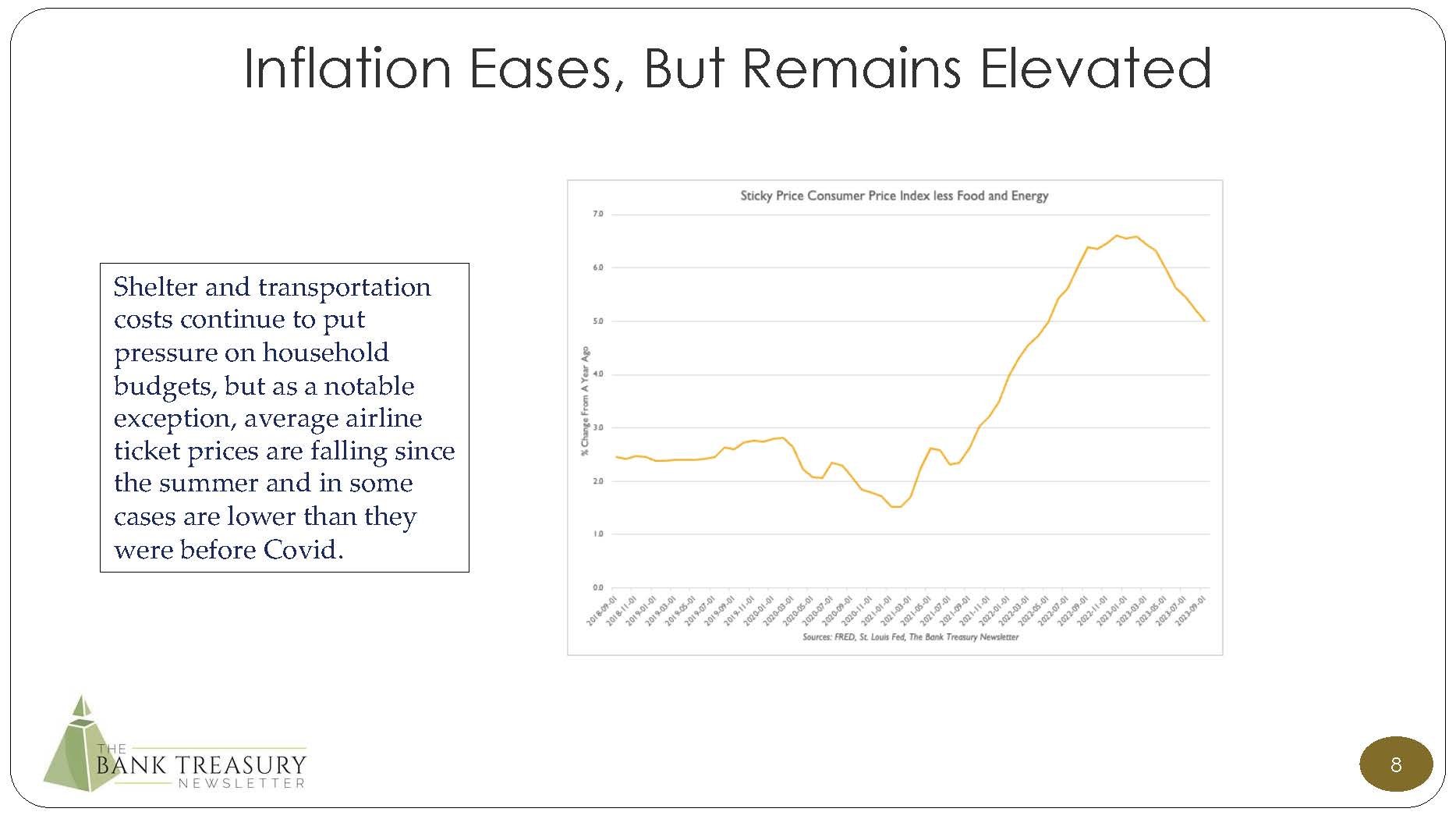

Inflation. It did not have a name back then, but people knew what it was, or thought they did. The term “inflation” as an economic term, first appeared in academic writings during the American Civil War, when the Federal government’s long history and fascination with greenbacks and trusting in God for their valuation began. The quantity theory of money (QTM) was not laid out until the economist Irving Fischer in the early 20th century who boiled it all down to the idea that the sum of money and the price of all goods and services must be equal. In other words, using the pencil theory of economics, if there are 10 pencils and $10, each pencil will cost $1. But if there are 10 pencils and $20, each pencil will cost $2. And so on.

And so, money supply’s connection with inflation was intuitive. What more did one need to know, except for the fact that in economics, nothing is ever simple. If it were, the U.S. economy should be deep into a recession by now. Economics is complicated even if the models are simplistic. Thinking is always changing, too. Inflation in 2023, according to Bill Dudley, former president of the New York Fed, is not related to money supply expansion anymore, unlike inflation in Irving Fischer’s day. If it still were connected, then there should have been a surge in inflation when the Fed expanded money supply after the Global Financial Crisis (GFC). But as Bill Dudley told a Financial Times interviewer this month it,

“…didn’t happen…If you go look at M2 growth after the GFC, you saw a lot of QE, you saw rapid growth of M2. And there was no inflation, no consequence for growth. M2 just doesn’t have much relationship to economic activity. People just don’t understand how the Fed’s operating model has changed. Quantities of money don’t really matter very much. What really matters is the interest rate that the Fed sets on reserves.”

The Fed’s world is one where reserves are ample, a world where there will always be more reserve deposits than needed by banks to meet their liquidity and payment needs. Call that ample, call it just abundant. The term does not matter. In this brave new world, money supply is not a critical factor driving economic activity or inflation. Economic activity today is driven by IORB, and the interest rate paid to money market funds for their cash investment in the RRP. Or at least that is the theory. When it met earlier this month, the FOMC voted to hold these rates at 5.40% and 5.30%, respectively.

Nothing about economics is ever as simple as its models, whether they are sophisticated macroeconometric models or just simpler price of pencil models. Economics is not even a real science, and the governing principles today may fade in importance tomorrow. Before the Fed’s ample reserve policy confused everyone, economists rarely agreed on anything. Economic historians remain divided, for example, on what caused the inflation in the 16th century as much as Fed economists today remain baffled by economic trends. And even if they had a good understanding, the Fed’s monetary policy toolkit remains a relatively blunt instrument, as Chairman Powell recently conceded.

What caused the inflation in the 16th century? It is true that Spanish, and Portuguese adventures to the new world in the 16th century left western kingdoms flooded with gold and silver doubloons which the QTM economists would say is a textbook example of money supply expansion causing inflation. But other economists say not so fast that population growth, which had rebounded after the Black Plague in the 14th century, drove the inflation. Much like today. Inflation could be temporary, it could be structural, it could be caused by the stimulus, or Covid, or who knows.

There were no bank treasurers on the Mayflower and there were no economists. But if economists had been on board, they could have regaled the passengers with their competing theories of money supply and inflation. For sure the Pilgrims, who were probably seasick given the storm-tossed state of the Atlantic Ocean around hurricane season, for whom money supply would be the least of their worries when they got to the promised land, might have appreciated the distraction.

And if bank treasurers had been on the Mayflower, they would have appreciated hearing economists show everyone that they have no better idea about the direction of the economy than anyone else. But could someone please explain why the average price of a dozen eggs is $2.09 today, was twice as much last year, and was just $0.60 in 1950? Does price have anything to do with value? Not always. Everything depends, would be the answer economists would have to say.

If there had been economists on the Mayflower, they would have stuck to consensus. In the long run, everyone will be dead, but if economists were around back then, they might have flipped the script and probably told the passengers that in the short run most everyone on board will be dead within the first year from starvation, cold, and disease, but that in the long run Plymouth Rock would be a great place for bank treasurers to work, and that there will be two dozen bank and credit union branches in town all competing intensely for deposits, willing to pay north of 5% for CD money. They would tell the Pilgrims to just think of the economics. Plymouth Rock will become a tourist destination, located right off Court Street just south of the junction between State Routes 3A and Route 44 in Massachusetts, that people would be coming here in 400 years to vacation for the summer, clogging up the roads to the grudging annoyance of their future descendants.

If there had been economists on board the Mayflower, they would have stuck to consensus because they would have known that making a forecast is dangerous business. Back then, of course, making predictions about the future was tantamount to sorcery, a crime punishable literally by being drawn and quartered. Thus, the first rule of predictions is to not step out on a limb, unless you want to be pulled apart, literally limb from limb. And if stepping out on a limb is unavoidable, to not go it alone. But then again, consensus can be wrong, too, as it has been in this cycle. So, who knows. Certainly not economists.

Perhaps mindful of that conflicted school of thought, as much as economists at the Fed want to declare victory over inflation this time as numbers coming in show it receding and the economy remaining solid, they cannot rule out a recession. Everyone has been wrong. Bill Dudley continued,

“My view for two years was that we were going to have a recession at some point, because the Fed had let the unemployment rate get well below the Non-Accelerating Inflation Rate of Unemployment (NAIRU). And this is coming back to the Sahm rule. I have always thought that once the unemployment rate goes up by more than a certain amount, the chances of recession go up dramatically. Now what we’re finding is maybe that’s not the case. That’s the key question right now: does the unemployment rate have to rise to 4.25-4.5 per cent for the Fed to achieve their “final mile” on getting inflation back down to 2 per cent? If you think it does, then a hard landing is highly likely.”

Claudia Sahm herself questioned the wisdom of relying on the rule that bears her name, speaking to the same Financial Times interviewer a week later,

“I spend a lot of time reminding people that the Sahm rule is an empirical regularity. It is not a law of nature. Just because it worked in the past to signal early in a recession does not mean that it will necessarily work this time, because all kinds of empirical regularities have broken down in the post-pandemic recovery… So, the Sahm Rule breaking would be if it hits half a percentage point, which would be consistent with unemployment running about 4 per cent for three months, but we don’t see a broad-based contraction…The impossible is possible though and that’s been the theme of this year.”

We should be deep in recession by now and unemployment should be up. But unemployment is low even by the standards of good times, and GDP continues to expand. In fact, not counting the technical recession during Covid, the U.S. economy has been expanding steadily since the recovery from the GFC, the longest peacetime expansion in history, defying all the economic rules and assumptions about the role of interest rates on economic activity. Supply chain pressures as shown in the New York Fed’s index (Figure 1) are at the lowest level they have been at since the GFC. Employment remains resilient, and employees are earning more than the rate of inflation, buoying services inflation.

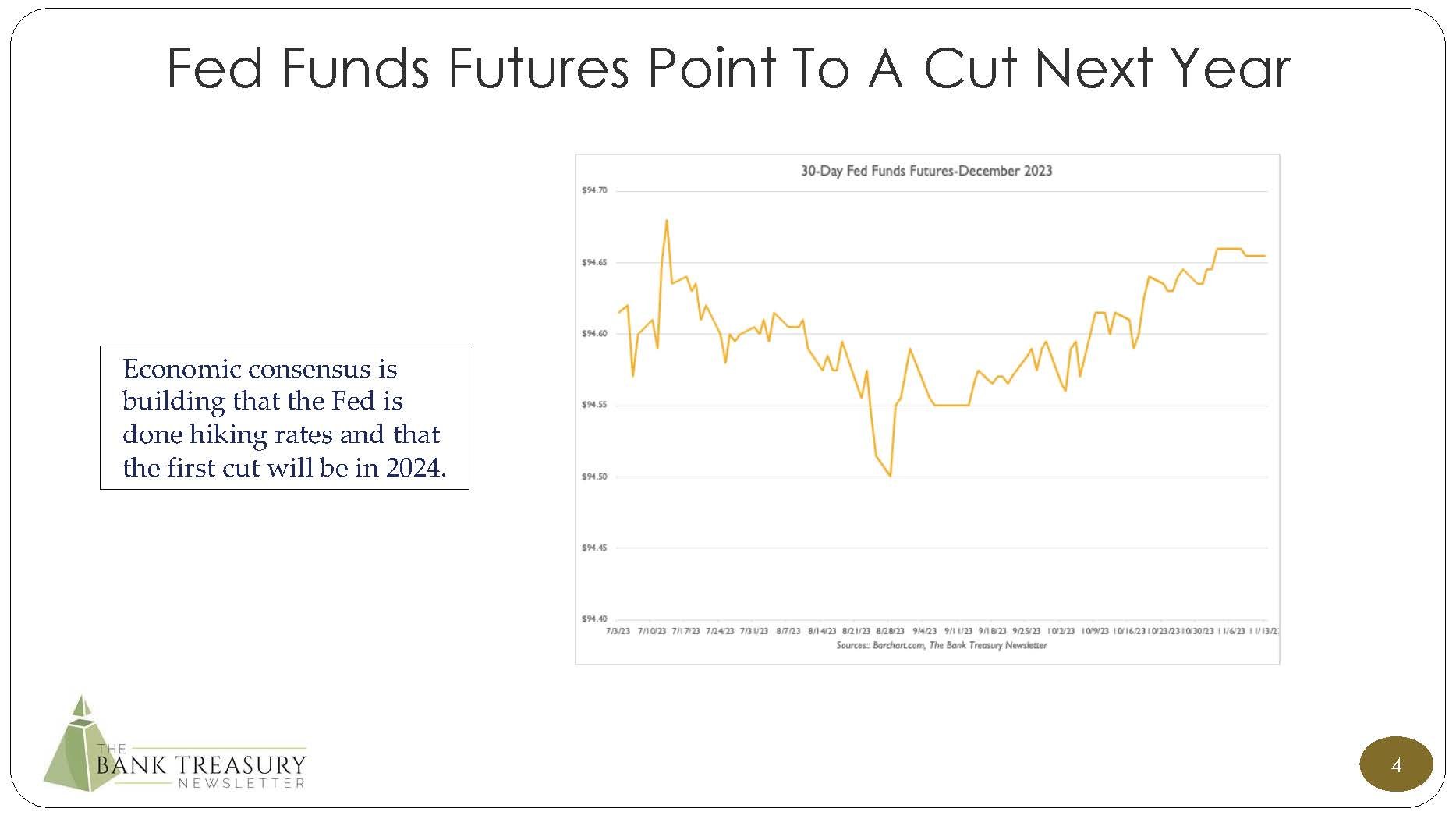

And economic consensus continues to predict that a recession is coming in six months, a prediction that the New York Fed’s Survey of Market Participants has been reporting ever since the Fed first began raising interest rates 20 months ago. Following the first rule of forecasting, that no prediction is ever wrong, just early, in the September 2023 survey, 75% of participants expected the U.S. economy to slip into recession by the end of 2024, and most (57%) were in the H1 2024 camp. In the September 2022 survey, 50% predicted that the world would be in a global recession by now. The trend in Fed Fund futures (see this month’s chart deck, Slide 4) is based on this expectation.

The art of economics could best be understood as the art of making predictions long enough into the future so that, if they turn out to be wrong, no one will remember who to blame. But six months for a recession to materialize seems like a short enough time even for short-time minded fixed income traders to remember who said what. If there had been bank treasurers on board the Mayflower, they would have remembered what the economists had told them.

Because they are the balance sheet trigger-pullers as far as the CFO, CEO, and everyone on the board of directors is concerned. They are the ones to blame when the bond portfolio is underwater like it is now. If rates had not increased in 2022 and 2023 and bank treasurers had sat in cash instead of moving cash into bonds, they would have been the ones to blame for not generating enough net interest income.

Their job is to take in the economic opinions, synthesize them as they apply to their bank’s balance sheet, and execute asset-liability management. Bank treasurers will remember. Especially now when things have not gone so well with the bond portfolio, and investors are anxious about narrowing NIMs. Bank treasurers’ day to day includes deposit and funds transfer pricing, covers the bond portfolio, whether to buy, sell, hold it, or hedge it, and care for the cashflows running on and off their balance sheets. They rely on economic predictions to do their job all the time. So, if they are going to be held accountable for mistakes, they will remember who to blame.

Figure 1: Global Supply Chain Pressure Index

Bank treasurers were not on the Mayflower because there were no banks back then, but had they been on board, their skill with pricing and managing funding resources would have come in handy when the Pilgrim leaders were talking to the Merchant Adventurers. When interest rates were at 0%, in search of earnings efficiency, there had been a trend in the executive wing, especially among smaller regional banks, to eliminate the role of bank treasurer, and merge it with the office of the CFO. But bank treasurers show their worth in times like these when rates are high, and even with the liquidity crisis in the spring faded from market memory, their profession is more necessary than ever.

That is why the CEO, president, and chairman of a regional bank in the southeast told analysts this month that the bank’s focus on treasury was nothing new and was viewed in his organization as mission-critical.

“One of the things that we've been talking about improving is our funding…We invested in treasury…We brought on…new people in that area. We've added…new solutions in the last 2 years. And so, it wasn't like March 10 or 11, we said, gosh, deposits are important. We've known that we needed to improve our funding cost and the diversity of our funding.”

Having made enough mistakes in their career to know that predicting anything can be fraught, they are inclined to avoid assuming interest rate risk unless they are sure they are going to get paid for it, and as any experienced hand will tell you, inverted yield curves are bad for getting paid for rate risk. They are the ones who can be depended on to keep a handle on balance sheet liquidity. They can be trusted to be disciplined when pricing deposits, when depositors are demanding rate relief, and there is panic in the boardroom.

Pricing is key, especially in a high interest-rate environment, as the CFO of a large regional bank in the northeast told analysts,

“In a high-rate environment, banks can make a lot of money. It comes down to the discipline how you price your assets and your deposits.”

The CFO of a large regional bank in the southeast agreed that deposit pricing is critical at this time like this,

“We spend a lot of time thinking about the efficient frontier around our liabilities management…We have been thinking about exception-based pricing and local authority. We made some adjustments to that, which we saw come through, which was great. Just changing the mindset. If you're a frontline teammate, in March, April, you probably had one sort of mindset and mandate, and that's changed in Q3 as we think about retaining and acquiring clients…We've been adjusting promo rates on the money market side. We've had a little bit more interest in CDs, not surprisingly, as some of the depositors want to lock in rates.”

And listen, in a lot of banking markets, competition for deposit funding can be cut-throat. You need a disciplined hand in charge of deposit pricing as the president and CEO of a mid-size regional bank in Maine explained during his quarterly analyst call earlier this month,

“It's still extremely competitive on both sides, but especially deposits. As you and a lot of folks know in Maine, we have a lot of credit unions, a lot of mutuals they tend to see their loan-to-deposit ratios run higher. So, they're pricing up deposits to reflect that. And so…it's almost like hand-to-hand combat on deposit pricing, but we're prioritizing relationships versus transactions.”

Relationships are key, and especially with retail depositors who, unlike commercial depositors, remain very sticky, as the treasurer of a large regional bank in the Midwest told analysts,

“The lessons from March were really that just how incredibly valuable retail deposits are and how fickle commercial deposits can be. And that has a huge impact then on how you think about valuing a deposit franchise and it has a huge impact on how we think about valuing relationships. Because it's a recognition that the economics associated with the commercial deposit relationships aren't what we had anticipated pre-March madness.”

It is the treasurer’s job to understand the bank’s depositors, the insured and the uninsured, the ones who needs a market rate, and the ones who could accept less. You need a bank treasurer to identify the best place in the time deposit space to compete and who to offer 5.6% for a CD. Someone responsible to predict when the downward shift by depositors from noninterest-bearing deposits into interest-bearing will stabilize (Figure 2) and to do the calculations to see how that change will play out with the bank’s NIM. And it is not an easy job. As the CFO of a large regional bank in the Northeast told analysts,

“I think the hardest thing…is modeling the disintermediation that's occurring in the industry. For us, it's the reduction of our demand deposits going into sweeps. We saw it moderate in the third quarter. We're expecting it to continue to moderate in the fourth quarter. But that -- obviously, when you lose something that you aren't paying interest on--you must pay 5% interest on it--that has an impact on your net interest income.”

The CFO of a small regional bank in the mountain states was seeing the same moderating trend in deposits,

“We saw a slowing in the mix and the shift that was going from noninterest bearing into interest bearing accounts.”

A dedication to the efficient frontier ultimately requires bank treasurers to refine their measures for risk and return. A lot of the large banks are talking about their banks going on risk-weighted asset (RWA) optimization diets, shedding business that does not add shareholder value. The president and CEO of regional bank in the southeast described the new thinking at his bank,

“When you're in a 0-interest rate environment, it's a whole lot easier to go out and take a chance on a loan-only relationship or to price something a little more aggressively when you're trying to win new business because wholesale funding is pretty cheap. If rates are going to stay higher for longer, one of the things we have to be better at is ensuring that when we're deploying capital, if we're exerting effort, that we're doing it with clients that are going to hurdle with our minimum returns on capital, that they're going to give us a full share of wallet.”

Figure 2: Domestic Noninterest-Bearing Deposits % Total Domestic Deposits

There is no choice, explained the CFO of a large bank in the southeast.

“Look, our cost of doing business increased and is increasing. And so as we think about how we allocate capital and the returns that we expect on capital and our delivery model, we have to be more disciplined…We're still facing some creeping liability costs as the betas grind a bit…but we are seeing some widening in the credit spread which has been welcome.”

And bank managers are determined to walk away from business that does not meet the hurdle. Some of that business will go to private equity investors, which as far as the CFO of a large regional bank in the Midwest was concerned is just fine by him,

“The private credit markets are taking share and they're taking share…on deals that we are not executing on not deciding to do they're taking half a turn or so more in leverage with looser credit structures, but they're also getting paid for it with wider spreads. So that could play out very well for them or it may not.”

The efficient frontier involves both sides of a bank’s balance sheet, as bank treasurers at banks of all sizes plan to hold more cash, less duration in their bond portfolios, and to model their deposits for shorter duration. A CFO from a large regional bank in the northeast explained how a reexamination of his bank’s uninsured deposits led to changes in how the bank was thinking more broadly about balance sheet liquidity and NIM. What changed since March?

“What we didn't model was the insured uninsured. So, now we're factoring in that volatility into our liquidity stress scenarios. That adjustment for us that we started to implement was an increase of…highly liquid assets…It doesn't have to be all at the Fed. It can be the Fed or in the investment portfolio or whatever. But it is something that we basically will have more liquidity available. That will put pressure on the NIM depending on the shape of the yield curve, it may or may not impact NII a whole lot depending on how that plays out.”

The CFO of a large regional bank headquartered in the Midwest attributed some of the mistakes made in his deposit modeling to the speed of the rate hikes,

“The speed in which the Federal Reserve moved up interest rates brought attention to deposit rates, and I think that changed behavior faster than what perhaps models would have indicated previously.”

Exactly, agreed the CFO of a large regional bank based in the west. Rates moved faster than expected and the behavioral response from depositors was not foreseen. This is what needs to get better when bank treasurers ask what could they learn from the events of March.

“We knew that there was going to be adjustment coming in 2023…Of course, we didn't see everything that was going to happen in 2023. And what happened was a pretty significant acceleration of that deposit repricing.”

When they finish pricing up deposits, bank treasurers will need to confront the mess in their bank’s bond portfolio. Some are content to sit on the portfolio and others are going to sell bonds. But either way, the negative mark has been difficult to swallow from a capital and earnings perspective. Even selling the bank and retiring to a golf course is not much of an option for bank treasurers who have seen enough to know bad times are ahead. From the buyer’s perspective, to take on another bank’s underwater bond portfolio would be a stretch at this time, as the CFO of a large regional bank in the Midwest said,

“The rate marks on loans and securities are so wicked, you'd need a 150 to 200 basis point further rally…to even be possible.”

The CFO of another regional bank in the west defended his bank’s decision to hold off on restructuring the portfolio.

“We're aware of some of the actions that folks have been taking over the past quarter. We're continuing to monitor those sorts of things. I think as time goes by, it seems like maybe we get more and more open to some changes, but nothing imminent from that perspective. We're aware of what's going on out there. We see what people are doing. We understand why they're doing those things. And every balance sheet is different, and ours is different, as well.”

Selection is key when it comes to the portfolio, and experience in knowing how to take interest rate risk is required. The treasurer of a large regional bank in the Midwest told analysts this month that despite the adverse marks in his portfolio, there was still a place in his bond portfolio for duration,

“You must be able to put some duration on your balance sheet in some spots to make sure that you're managing across a range of outcomes…We put some duration in the investment portfolio. We try to do it in a very disciplined way, where we minimized extension risk and we minimize prepayment risk because that's one of the biggest risks from an investment perspective is being forced to reinvest at the worst times as many of us are now seeing across the industry as people put huge amounts cash flows from an investment portfolio into residential mortgages at the worst time.”

Bank treasurers are hedging some of the risk in the portfolio that rates can go higher from here. The CFO of a large regional bank in the west told analysts how he was hedging his bond portfolio with receive floating/pay fixed swaps, which was one of the asset-liability management tools at his disposal.

“We put on a portfolio layer hedge on the investment portfolio. And so that would be -- over the course of the second and third quarter, we had a lot of balance sheet hedges, interest rate swaps, received fixed swaps that we canceled and took those off and in fact, put on a received variable rate -- set of received variable rate swaps. And those are hedges against the AFS portfolio value. To the extent interest rates have gone up here since those hedges were put in place, that has effectively hedged the value, not the entire value, but it's provided a hedge to the AOCI and therefore, has dampened the effect of the changes in interest rates, on the tangible common equity (TCE) ratio.”

TCE is a dumb capital ratio as any bank treasurer knows, but under FHFA rules a positive TCE ratio is generally required for an FHLB to extend an advance to a member bank. When mark-to-market in the available-for-sale (AFS) portfolio last year began to threaten their solvency, banks campaigned to eliminate the requirement, but to no avail. Since the failure of Silvergate, SVB, SBNY, and FRC this year, the FHFA is happy it ignored those demands as it noted in the FHLB100 report it released earlier this month.

Financial regulators were also not on the Mayflower, but if they had been, they probably would have issued a cease-and-desist order against the Pilgrims considering the loan terms and the physical safety issues on board. Literally, the Mayflower might have been a shipping disaster waiting to happen, like SVB and SBNY when they failed. Whether anything would have been done to correct the matters requiring immediate attention before it sailed will forever have to remain unknown.

Similarly, bank treasurers, who might be worried that the FHFA should leave well enough alone with the FHLBs, may be reassuring themselves today after reading the agency’s report that, if any changes do come to the structure of the FHLBs, their lending procedures, or their membership eligibility requirements, they will not become a reality any earlier than 2025, considering how long it took for the release of the FHLB100.

Nothing in the agency’s report should have been a surprise, especially not to readers of this newsletter who just read about it here in last month’s edition. Number one, the FHFA, siding with the newly scandalized Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC), insisted that the FHLBs are not a lender of last resort to financial institutions in need of an emergency loan.

“The role of the FHLBanks in providing secured advances must be distinguished from the Federal Reserve’s financing facilities, which are set up to provide emergency financing for troubled financial institutions confronted with immediate liquidity challenges. Due to operational and financing limitations of the market intermediation process, the FHLBanks cannot functionally serve as the lender of last resort, particularly for large, troubled members that can have significant borrowing needs over a short period of time.”

And it should come as no surprise to our readers that the FHFA believes, like all financial regulators these days, that credit underwriting needs to be updated. Artificial intelligence and machine learning technology provide lenders with an ability to see through a cloud of data and is increasingly finding its way into credit underwriting. FHLBs have historically relied on the valuation of a member’s eligible collateral and its super-lien if the member fails. But from the FDIC’s perspective, the FHLB’s claim on the collateral for repayment comes at the expense of the Deposit Insurance Fund, which was seriously dented by the failure of Silvergate, SVB, SBNY, and FRC. At the time of their failure according to the FHFA, advances to them totaled $74 billion, all of which were repaid to the FHLBs by the FDIC. As the report went on to say,

“The FHLBanks’ model of providing liquidity primarily through secured advances should be accompanied by a thorough and regularly updated credit evaluation of their members to avoid encouraging excessive risk taking.”

To the FHFA this was a key point. The FHLBs were on notice to make this known to their members. It will not be enough that a member has positive tangible common equity (TCE) to extend credit anymore. The FHFA wants more,

“As a result, FHFA is actively monitoring the FHLBanks’ lending activity and has provided guidance to them to reassess and update their member credit frameworks. Additionally, FHFA has provided guidance to the FHLBanks to improve communication with members regarding the FHLBanks’ limitations on extending further credit when a member’s distress signals potential failure. FHFA has also emphasized the importance of capturing all appropriate dimensions of risk when assessing member creditworthiness and that the FHLBanks should not rely primarily on collateral to mitigate risk in tenuous situations.”

To be eligible for membership, 10% of a bank’s assets must be concentrated in residential mortgage assets at the time of application for membership. Silvergate, for example, met the 10% rule eligibility requirement when it became a member of the FHLB San Francisco, but not upon its failure. On the other hand, SVB, SBNY, and FRC met the 10% requirement even when they failed. Although on average the system would seem to meet this requirement handily, based on a survey of Q3 2023 call reports, more than 700 institutions, most under $10 billion in total assets, would not meet such a rule. Nevertheless, the FHFA wants to make the requirement permanent, at least for certain currently unspecified members.

“To ensure that members continue to support the FHLBank mission, FHFA plans to initiate a rulemaking to require that certain members have at least 10 percent of their assets in residential mortgage loans or equivalent mission assets…on an ongoing basis to remain eligible for FHLBank financing.”

The FHFA believes that more needs to be done to increase the number of Community Development Financial Institutions members, but there was no mention in its report about extending membership to fintech companies such as Quicken and Rocket Mortgage which dominate the residential mortgage market. The FHFA also said it was considering consolidating the eleven FHLBs if it would improve the efficiency of the system and was always encouraging the FHLBs to discuss mergers on a voluntary basis if they believed they made sense. It does have the statutory authority to merge FHLBs on its own if for the good of the system, but this power is limited by a rule that requires that there be no less than eight banks.

Bank treasurers are repaying advances these days as the liquidity pressures from the spring abate and they see both loan growth and deposit outflows slowing. Some smaller community banks are not seeing the same degree of a slowdown perhaps finding themselves funding some of the business that larger institutions on their RWA optimization diets have let pass by. But the message from publicly traded banks was that adverse funding trends are easing, if not even reversing somewhat as some expect deposits to increase faster than loans in Q4 2023. The president and CEO of a small regional bank in upstate New York told analysts,

“We're seeing a slowdown in loan production given market conditions. I don't expect we will originate to that level in Q4. I would say probably as we sit here today, we probably are going to do probably something…less than that…And we do expect our deposit growth to exceed our loan growth in Q4.”

Higher rates are contributing to a slowdown in loan demand, according to the president and CEO of a regional bank in Maine,

“We are still increasing rates shooting up now, honestly, close to an 8% handle not there completely across all products, but, getting there. So that has slowed down the pipeline. One of the reasons why we saw a small reversal of some of our reserves was because of that.”

The economy was to blame for slower loan demand according to the CFO of a large regional bank in the southeast, which on the positive side, tempered his appetite to pay up for deposit funding,

“We're not going to see a lot of loan growth in this fourth quarter and probably not going to see a lot of loan growth next year because the economy is going to continue to slow down. So, you don't have the dynamic where you're having to chase deposits to get the funding for loan growth. You don't have to leverage that and get brokered deposits and high-cost deposits…We don't see a lot of pressure on deposit outflows…that's stabilized since all the craziness that happened in March.”

Unless there is a significant increase from here in rates, and that is not the consensus among bank treasurers, everything will be fine NIM-wise. But a significant minority do not believe the Fed is done and most all believe the Fed is higher for longer no matter what the surveys and Fed Funds futures indicate about a cut next year. If this holds true, there would be some small further adjustments in deposit repricing, but the CFO of a large regional bank in the northeast told analysts this month that,

“The bulk of the repricing has probably occurred but higher for longer, we probably have some dribs and drabs of things would probably trickle in over time.”

If the Fed is done is a big if, said the treasurer of a large regional bank in the Midwest,

“There is probably just going to be continued migration…into CDs. We think it's going to continue to be a competitive CD market…. When we talk about both NII and NIM troughs, it takes about two quarters for the impact of the last hike to come through…In general…it will be very manageable from here if the Fed is done.”

There were no professional bank treasurers, regulators, or economists on board the Mayflower, for better or for worse. But even though the Pilgrims generally frowned on smoking, there were pipe makers and tobacco sellers. Smoking was probably a habit picked up from their time in Holland. Fortunately for the safety of the passengers, considering the flammable nature of the ship’s construction, tobacco was not on the supply manifest. But almost three centuries later, in 1911, two years before the creation of the Fed, Dutch Masters became America’s leading cheap cigar made in England. Let freedom ring!

The Bank Treasury Newsletter is an independent publication that welcomes comments, suggestions, and constructive criticisms from our readers in lieu of payment. Please refer this letter to members of your staff or your peers who would benefit from receiving it, and if you haven’t yet, subscribe here.

Copyright 2023, The Bank Treasury Newsletter, All Rights Reserved.

Ethan M. Heisler, CFA

Editor-in-Chief