BANK TREASURERS AT YEAR-END

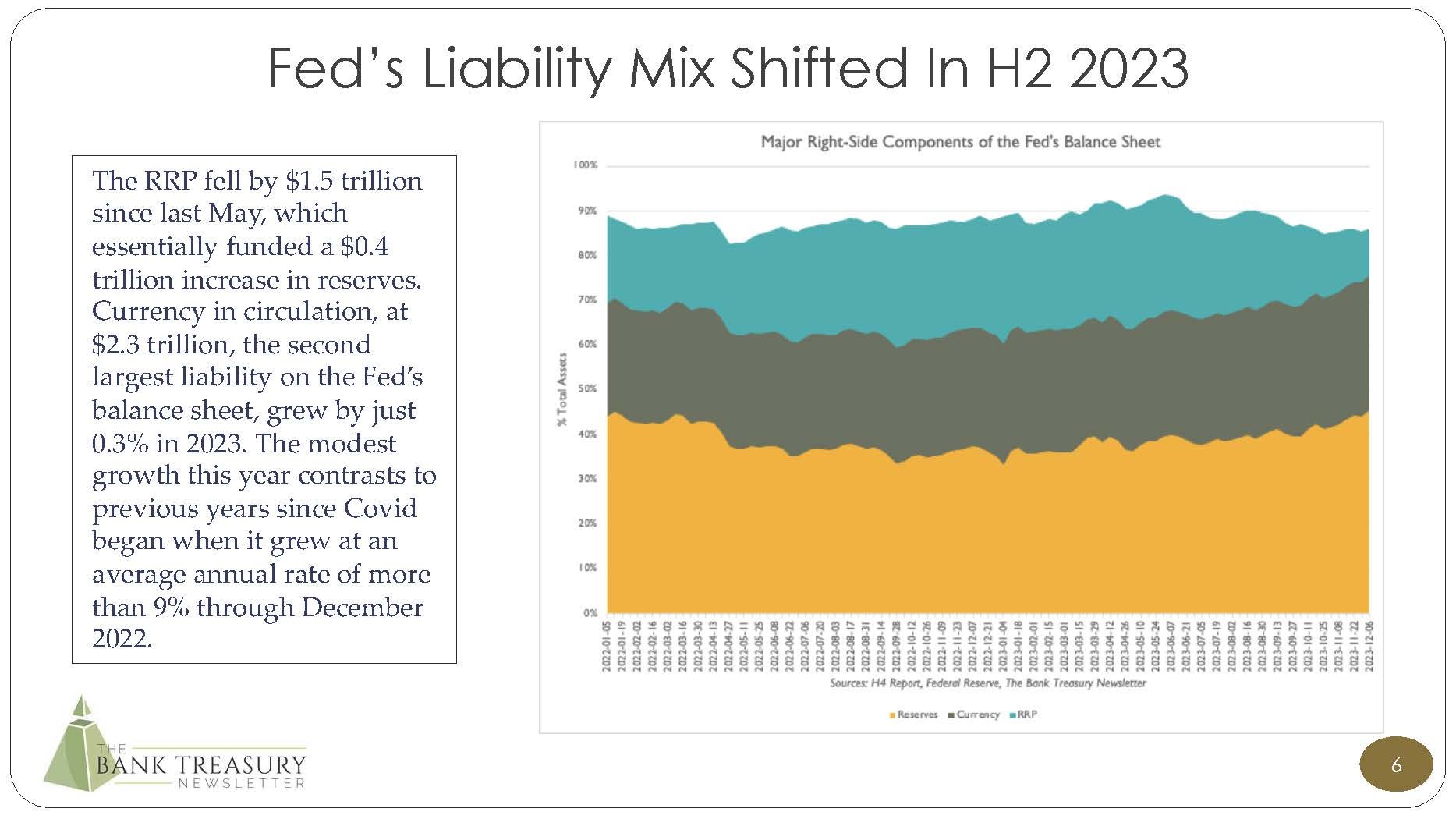

The Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) voted unanimously to maintain the range for the Fed Funds rate between 5.25% and 5.50%. It also voted to hold its two main levers to control the effective funds rate, the Interest rate On Reserve Balances (IORB) and the rate on the Reverse Repo Facility (RRP), respectively, at 5.40% and 5.30%. The balance of reserves increased by $0.4 trillion in the last six months, to $3.5 trillion, while the balance of the RRP fell by $1.5 trillion, to $0.8 trillion. Fed officials expect the RRP balance to continue to fall as banks use higher rates to attract depositors back from the money market funds.

The latest dot plot suggests that the committee’s rate outlook is trending lower and that it could reduce the range on the Fed funds rate by 100 basis points in 2024, to 4.25%-4.50%. By 2026, at the latest, the range could fall below 3%. Of course, this dovish outlook depends on inflation getting below 2%, which at just over 3%, as Fed Chair Jerome (“Jay”) Powell pointed out during his press conference, remains above target. The FOMC members also believe in a very soft landing for the economy, expecting unemployment, currently at 3.7%, to rise only modestly to 4.1% by 2025. Notably, bank management continues to report that their commercial customers are still struggling to hire and retain employees. In addition, despite their own official forecasts, most senior bank executives doubt there will be any cuts in 2024, or at least that the cuts will be pushed back to later in H2 2024.

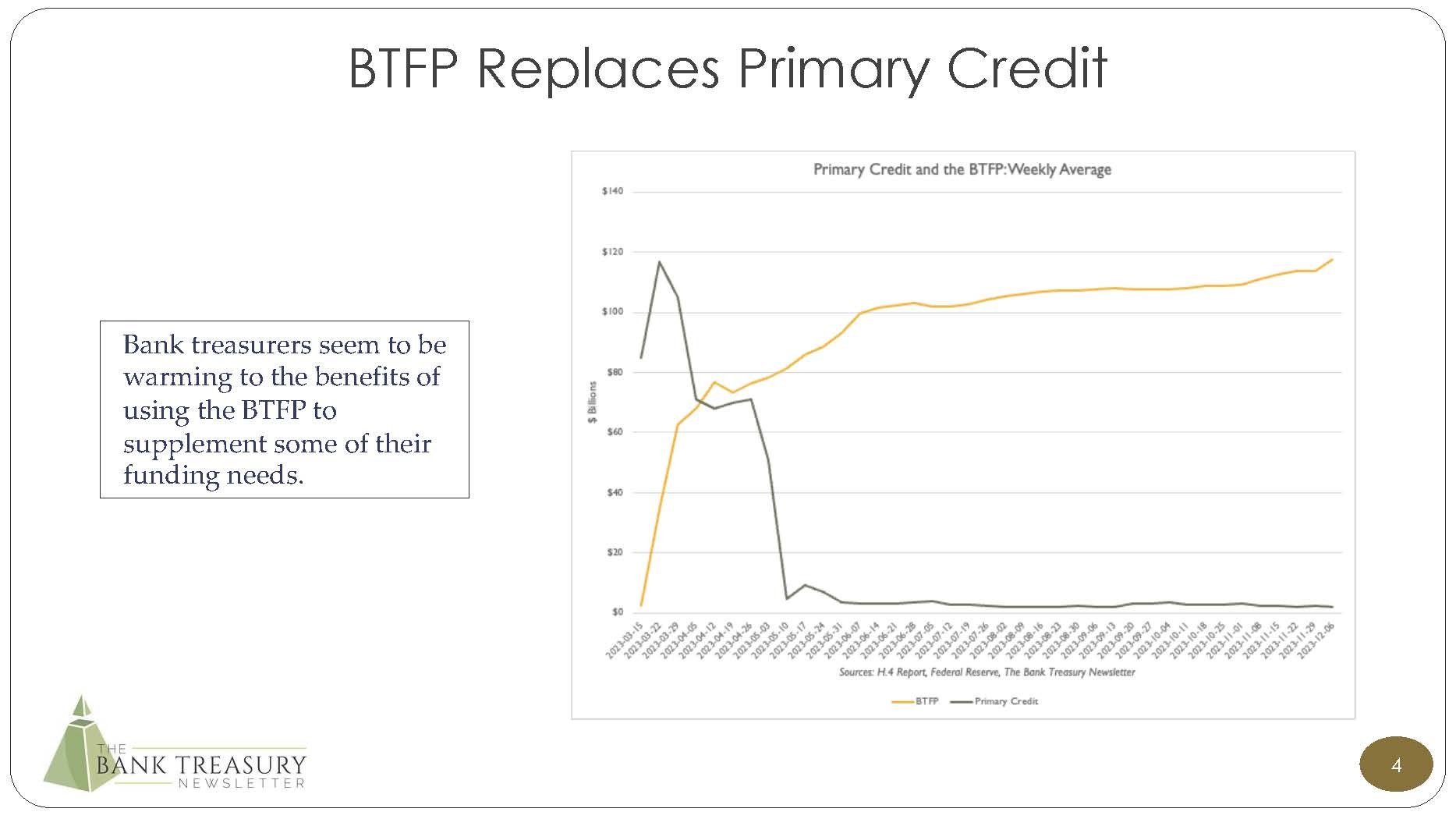

Primary credit at the Fed’s discount window will also remain at 5.50%. Michael Barr, the Vice-Chair of Bank Supervision, and a member of the FOMC, has been a leading voice demanding that banks turn more frequently to the Fed for an emergency loan and to not worry about the potential market stigma. Unfortunately, the Fed’s discount window, like the Federal Home Loan Banks (FHLBs), which the Federal Housing Finance Administration (FHFA) insisted in its FHLB100 report last month were not a lender of last resort, are only open during business hours, so neither the window nor the FHLBs could have helped Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) when it failed overnight or Signature Bank when it failed over the weekend.

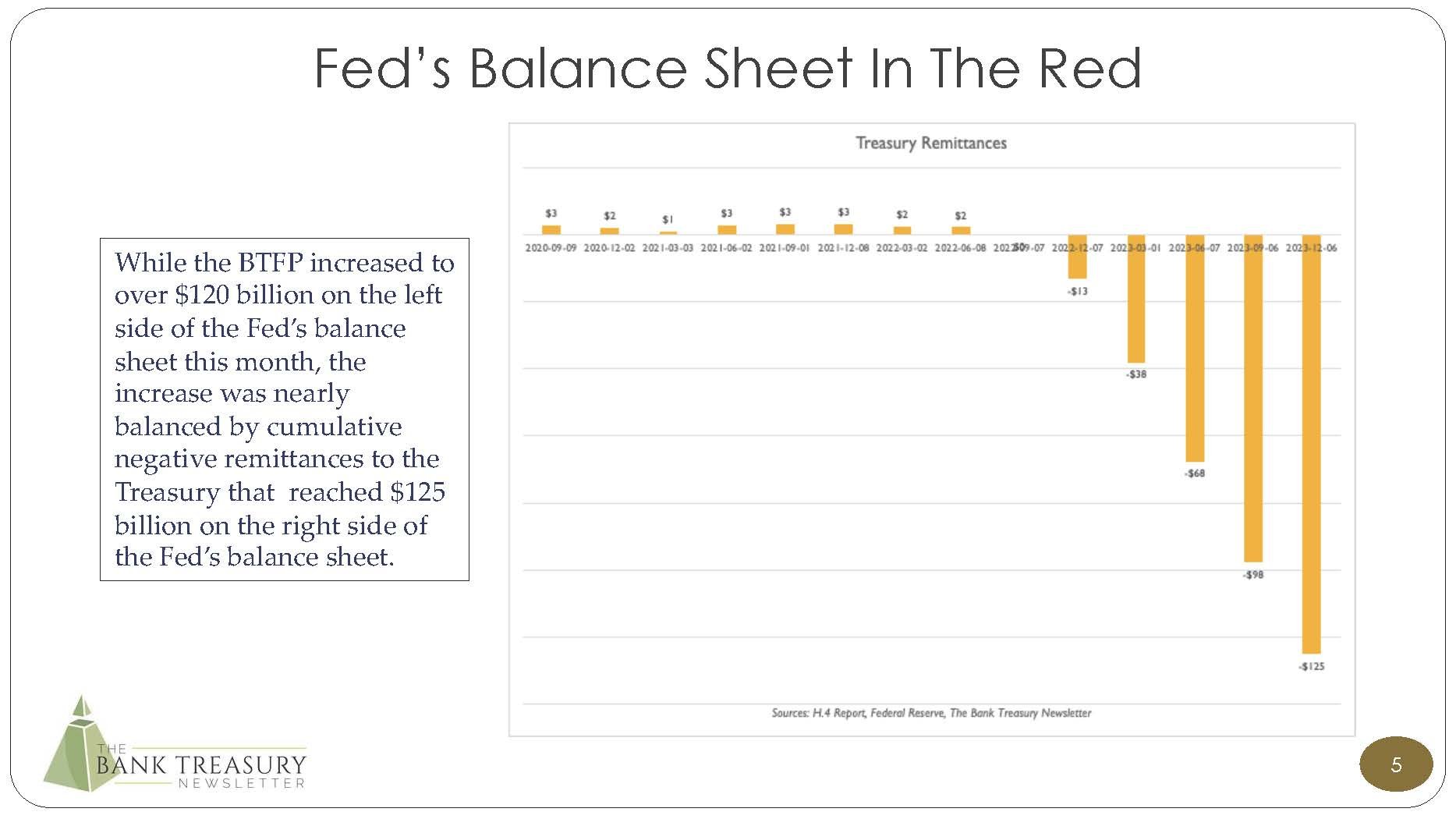

The balance in the Bank Term Funding Program (BTFP) account, which the Fed runs from the discount window, increased to over $120 billion this month, compared to $2 billion in the primary credit account, but this might be because the BTFP has much better terms than the window, including that the rate on the BTFP is 10 basis points over the Option Index Swap (OIS) rate. The average rate this month on the BTFP was under 5.20%. This means that the cost to borrow from the BTFP is not only well through the rate the Fed charges for primary credit, but through the lower bound for the effective Fed funds rate, as well.

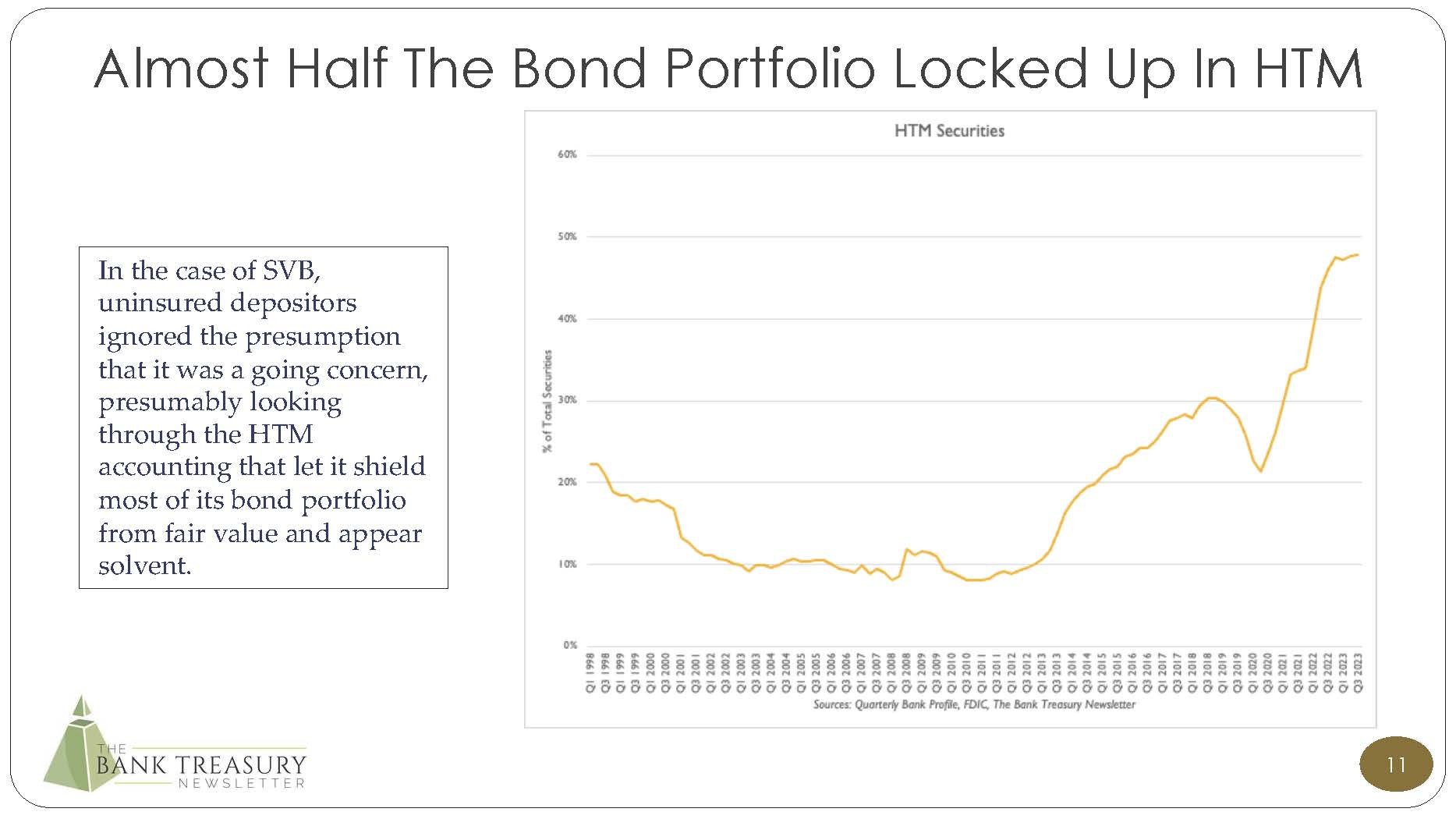

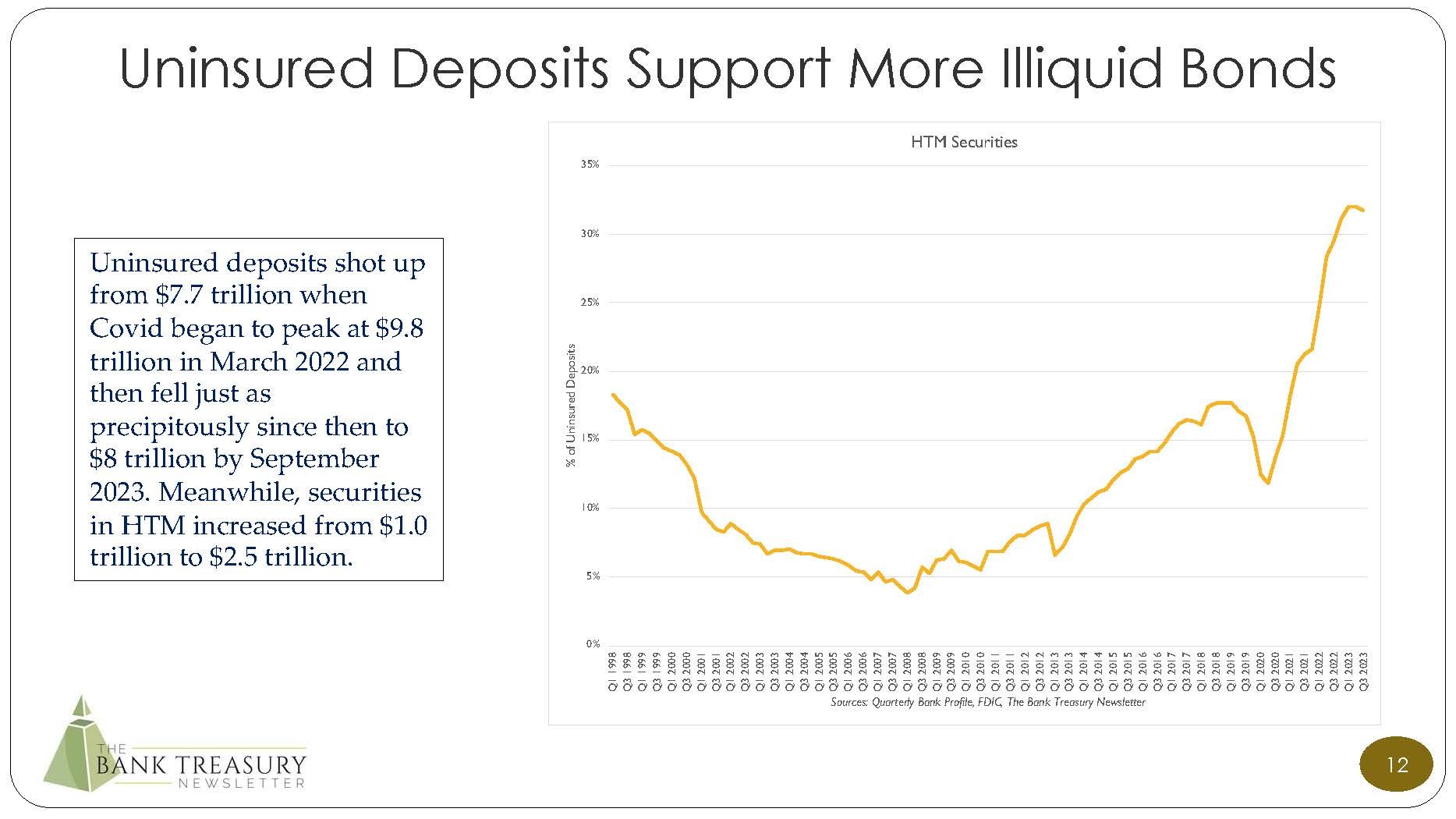

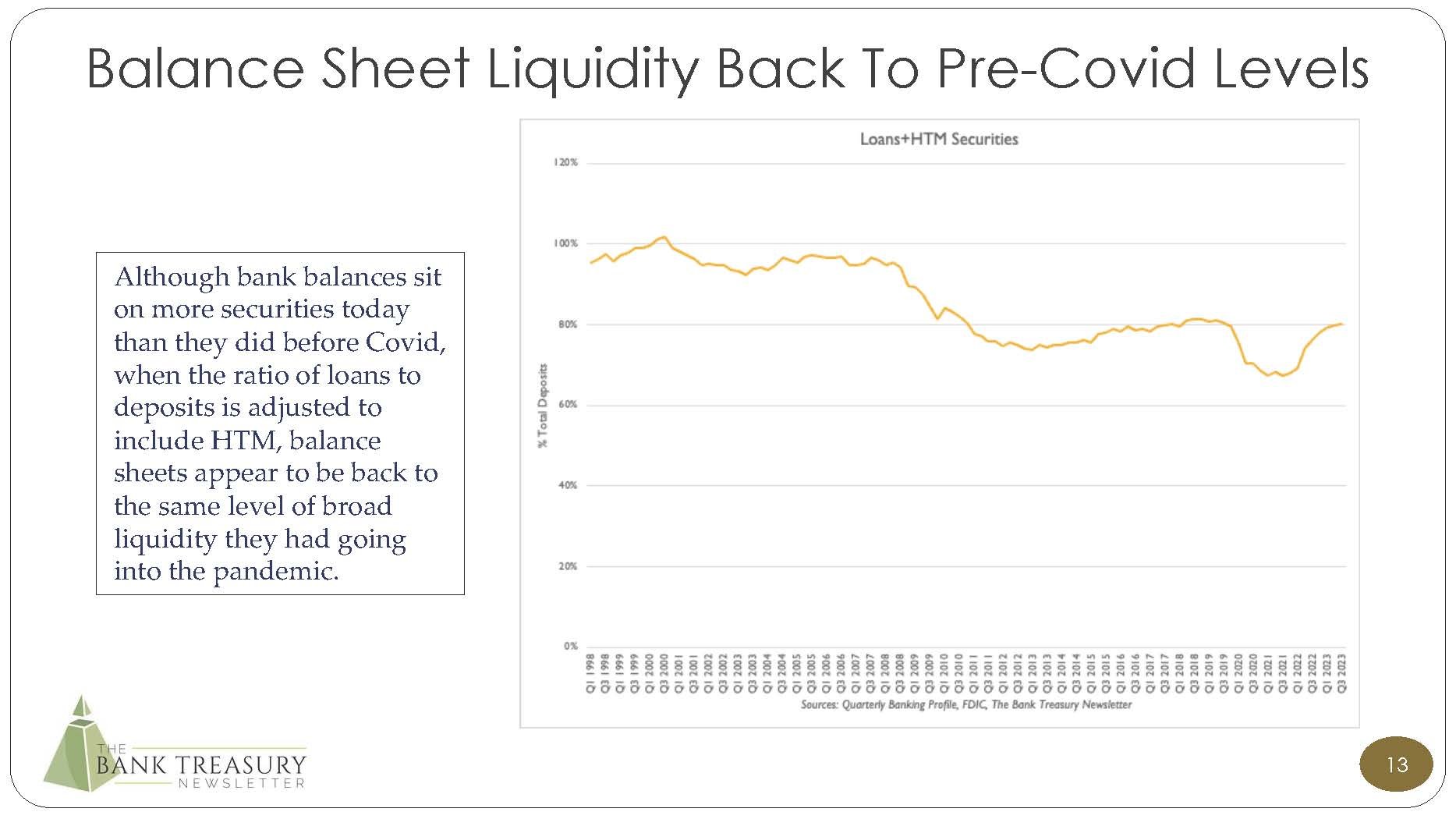

Speaking to a European Central Bank (ECB) forum on bank supervision this month, the Vice-Chair raised concerns, as have other bank supervisors and investors since the crisis last March, about banks counting on the held-to-maturity (HTM) account as a source of liquidity using the repo market. The latest Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) data shows that 48% of the industry’s bond portfolio is booked in HTM and therefore cannot be sold for operational liquidity purposes, unlike bonds held in available-for-sale (AFS). However, like the discount window and the FHLBs, the repo market does not operate off-hours. Even counting on the ability to sell securities from the AFS book during a market panic is questionable as part of a contingency funding plan. So far, there have been no explicit regulatory proposals aimed at curbing the use of the HTM account to shield capital from fair value changes in the bond portfolio. But that could change as regulators and standard-setters look to respond to lessons learned from the crisis last spring over the coming year.

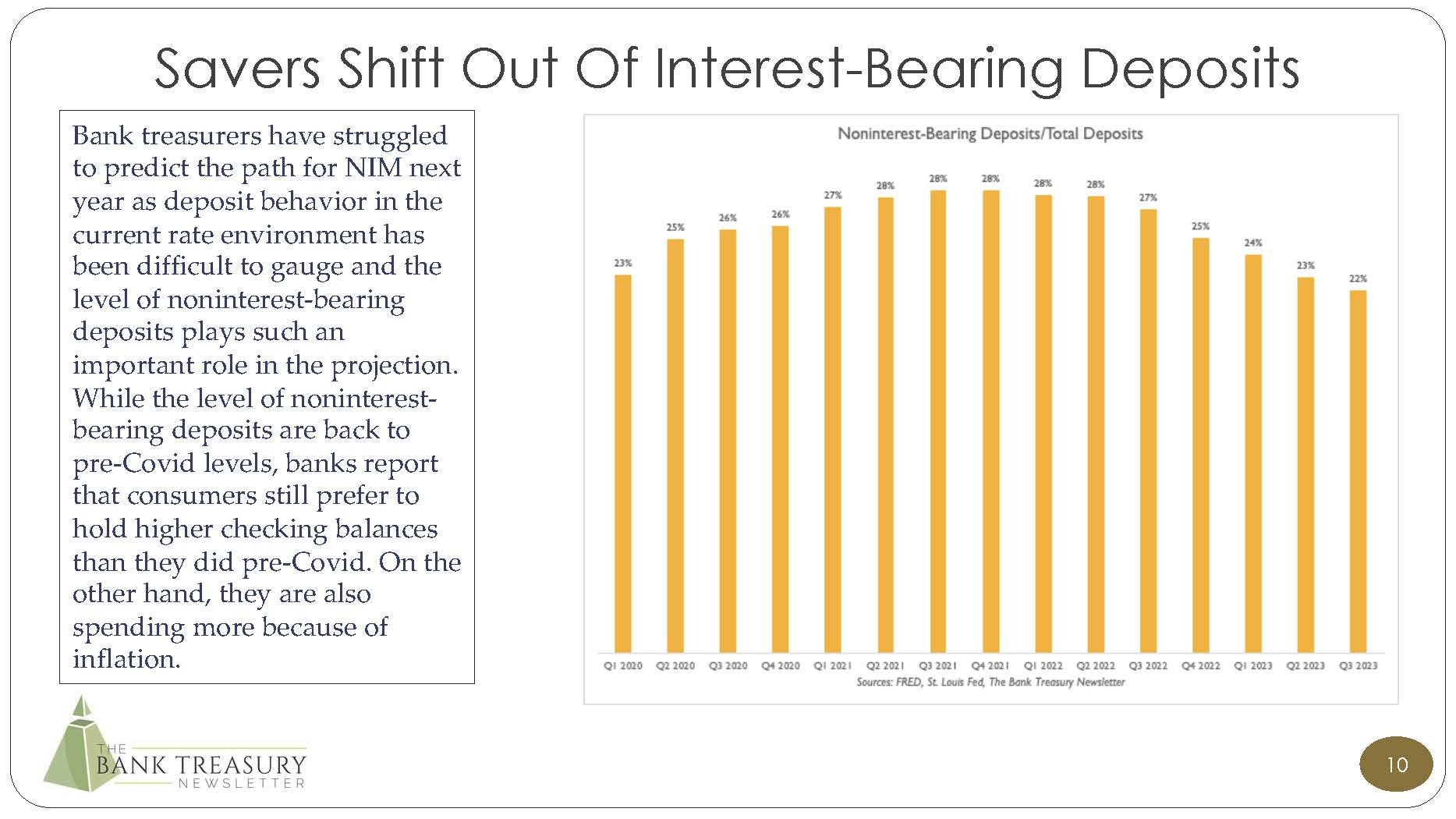

Therefore, for this and because of perceived changes in depositor behavior, bank treasurers plan to hold more cash on their balance sheets going forward, most of which will stay in reserve deposits at the Fed. Given the yield curve’s inversion, they continue to be very well paid to sit on the cash, but many anticipate that the yield curve will eventually return to a positive slope. The direction of noninterest bearing-(NIB) deposits remains their greatest unknown as they prepare their budget plan for net interest income (NII) and net interest margin (NIM). NIB deposits fell in Q3 2023 to 22% of total deposits, their lowest level since Covid began, and has proven to be more difficult to forecast as depositors balance their preference to hold more cash in checking with the inflated cost of their spending habits.

The deadline for comments on the FDIC’s proposed rulemaking that would require a bank’s board of directors to take a more active role in overseeing management passed this month. The proposal has raised significant concerns in bank boardrooms about potential conflicts of interest and the ability of boards to bring on new directors given the potential civil liabilities board directors would face. Under the proposed rulemaking, directors would not only be answerable to shareholders, but to other stakeholders, as well, including regulators, customers, and the public.

The Bank Treasury Newsletter December 2023

Dear Bank Treasury Subscribers,

Technically, the year still has a few more days to go, so what could really happen between now and the year-end? We are even past the last Fed meeting for 2023 and have not had any unpleasant surprises. Then again, as the saying goes, it is not over until it is over, or something about an overweight person singing. Some of our more “experienced” readers understand how the finish line can be a fraught affair in the bank treasury world. December is usually the month where vacations go to get canceled. Something about the time of year.

December is always full of surprises. Covid began on December 31, 2019. There was that giant asteroid that blew up in the sky in December a few years ago that scientists apparently never saw coming. Famously, the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) started in December which bank executives and economists also claimed they never saw coming. Those who remember those currency crises of yore, you had the Mexican Peso crisis in December 1984, followed by the Tequila crisis in December 1994. And of course, there are those always suspenseful will they or won’t they FOMC meetings that come up every December.

However, barring the unexpected, it is finally time to wind down in a comfortable, button-upholstered, armchair, and cozy up next to a blazing, roaring fireplace. Holiday libation in hand, a plate of holiday cookies on a plate nearby, we can look back on the year that was. December is the time of year to make resolutions for next year and prepare for the traditional year-end festivities in the office (for those who still come in). And if you think you have no time to sit back, think again. In this fixed income market of inverted yield curves, bank treasurers have never been better paid to just sit back, feel the warmth of the fire, and do nothing but roll cash overnight at the Fed at 5.4%.

Of course, there is never nothing going on. This is the time for termination notices, final farewell emails, and unscheduled meetings over revisions that people with higher paygrades insist need to be made to the assumptions for next year’s budget. This is the time when the client delivers the inevitable bad news you knew was coming but hoped against hope would not come. This is the month when the deadline falls for finishing up that information security training module that always got put off because keeping the bank from running out of money took precedence. No employee is above training for phishing and social engineering, not even bank treasurers. Remember that!

But leaving those lingering to dos aside, now is that most wonderful time of year to just stop and take a deep breath. Breath in, and now breath out. Do it with purpose and repeat if necessary.

Because breathing helps with listening. Apparently, this is what the whole business with meditation is about as the newsletter’s editorial team learned on a recent fact-finding mission to a local spa. And you do not have to get into an uncomfortable cross-legged position. You can do it from your desk chair. When you meditate you become aware of things you might have been blocking out when you were too busy panicking last spring about your deposit betas going from 25% to 100%.

It would help to really help to listen to what Fed officials have to say, for example. Does anyone really listen to them? No, we listen to the economists who tell us what they say. Bank treasurers are just too busy during the year to listen (or to read this newsletter for that matter, which is why The Chart Deck was launched, our newsletter in comic book format). They just want the cliff notes.

And the short and sweet from those Fed speakers is that rate cuts are coming. Make no mistake. Hooray! Maybe not as soon as they thought they would come earlier this year, in time for when Santa will come to town, but rate cuts are coming, make no mistake. Eminent economists are saying so in unison. And have been saying so forever, since when the Fed first began raising rates in 2022, which certainly feels like forever ago. No opinion is wrong, just early in the economic opinion business.

Paid to stand up at corporate gatherings and whisper sweet nothings into the ears of cash-happy investors, they sing with conviction in their hearts that rates are too high and will be lower. Tra la la la la and buy, buy, buy. But maybe not now. Did anyone say now? No, later, which might be soon. That is what consensus economists say that the Fed said. Buy now…later. Like the consumer retail trend that has been driving up holiday sales this year and no doubt has been helping stoke the latest GDP revisions.

Leaving their definitive interpretations on the fence where they belong, here is what Chairman Jay Powell told attendees at a fireside chat at Spelman College earlier this month. He started with an acknowledgment of the obvious. Inflation, that menace to the economy, that economic bogeyman that everyone’s parents and grandparents feared in the 1960s and the 1970s, that Gorgon that Paul Volcker slayed in the early 1980s, that his successor, Alan Greenspan, kept dead and buried into the early 2000s, which was so dead that Greenspan’s successor, Ben Bernanke, and then his successor’s successor, Janet Yellen, were left to contend with deflation risk, inflation’s even more dreaded sibling, which was then so buried that it lulled Jay Powell into believing that monthly reports in 2020-21 from the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics of ghostly inflationary apparitions were the product of transitory vapors, is finally receding along with this very long sentence into the long dark negative vibe of the American consumer’s wintery discontent.

But its presence lingers like a bad smell, and rest assured he said, it is neither gone nor forgotten over at the Eccles building on Constitution Avenue in Washington, D.C. where a merry band of brave inflation-fighting knights of the FOMC gather every six weeks around an oblong-shaped conference table. Jay Powell summarized the FOMC’s thinking for the assembled at Spelman College, telling them that,

“Inflation has declined to 3 percent over the 12 months ending in October, but after factoring out energy and food prices, which tend to be volatile, what we call "core" inflation is still 3.5 percent, well above our 2 percent objective.”

In November, annual year-over-year inflation cooled even further, to 3.1%, but it is still north of 2%. How can this be, though? The Fed raised rates to effectively infinity in 18 months and the economy did not roll over. It should have been flat on its back by now. In fact, a half-year after its last hike of the Fed funds rate to 5.25%-5.50%, the U.S. economy just printed 199,000 new jobs. Is the Fed still The Fed?

Frankly, is any central bank, even the biggest and most powerful, capable of reining in this economy, an economy so strong that the most negative characterization of it that economists can muster is that it is normalizing and returning to trend? And those are the most pessimistic economists. A soft landing or even no landing is the new recession. Honestly, how long can an economy go on before cracking over higher for longer, bank failures, tightening credit underwriting, deposit run-off, and a mortgage market in a deep funk? Apparently, for a very long time, as economists have been talking about soft landings since 2022.

No, no, do not despair, the Chairman told the group gathered around him, it is just about the lag,

“The strong actions we have taken have moved our policy rate well into restrictive territory, meaning that tight monetary policy is putting downward pressure on economic activity and inflation. Monetary policy is thought to affect economic conditions with a lag, and the full effects of our tightening have likely not yet been felt.”

Lag is an interesting word and has a long history in economics. The great Milton Friedman and Anna Schwartz, the father and mother of modern monetary policy, came up with the term in the 1960s. This was after studying a century’s worth of economic cycles. They found that the time between a change in interest rates and an economic effect could take anywhere from 6 to as long as 29 months.

Which means that if a soft landing, recession, or what have you, is coming in any sense of what is meant by causality, if the Fed’s current monetary policy of unprecedented cumulative rate hikes, quantitative tightening, and higher for longer means anything, if the Fed is something more than toothless, “it,” whatever “it” is, better materialize before August 2024, which is 29 months since the first hike. Otherwise, well then “it” might take longer, or this time is different. Who can be definitive about anything when it comes to economics?

But with all due respect to consensus and experience, how long is a lag before you conclude that Fed policy and the economy are decoupled? And what happens when that realization takes hold in the markets, when the investors listening to those dovish blandishments suddenly realize that they have been wasting their time listening to economic consensus. Maybe all the focus on recessions and inflation is beside the point? In all fairness, how do you get a recession or focus on a soft landing when you are still trying to hire more employees and retain them?

Even now, nearly two years since economists started talking about recessions and soft landings, the chairman, president, and CEO of a regional bank based in the Midwest told analysts this month at an industry conference that his bank’s commercial customers are,

“…still worried about getting people, getting enough workers, getting enough workers that want to work, being able to pay them.”

He was not alone in this view. The chairman, CEO, and president of another regional bank in the Midwest reported much the same about his customers, who were feeling generally optimistic no matter what the latest survey from the National Federation of Independent Businesses found, telling analysts that,

“The companies, the CEOs I'm talking to, the company is performing generally well. It's not record years in most cases. And backlog for '24, '25 maybe lighter -- is lighter in the majority of those, the confidence in sales, not at the same level as it was in the prior year. Having said that, they're having good years. They expect to have good years next year…This should be a good fourth quarter and confidence improving with the rate outlook adjustment.”

Can you imagine? Forget recessions. If the Fed wants to focus on something, it should focus on getting rid of all the uncertainty in the world because it is ruining everyone’s day. As the above-quoted bank executive continued,

“This is one of the most uncertain times I've seen in my business career. If you think about what's gone on with the 10-year just since October -- and first of all, we had the biggest hike in interest rates in 40 years. I'm told the decline in interest rates over the last few weeks is the most precipitous in the last half a century. There are obviously hotspots all over the world, whether it's Taiwan, whether it's Ukraine, whether it's what's going on in the Middle East. And so, I just think people feel good about their business, but I think people are just concerned about some of the unknowns out there, some of the same things all of us are dealing with day in and day out.”

Uncertainty and volatility go hand in hand. Thus, thanks to uncertainty, bank treasurers are left to figure out how to stay on a bucking yield curve without getting thrown. Even the most experienced treasurers have had their hands full this year riding an interest rate roller-coaster that can swerve in any direction when least expected. This is no time to buy or sell, but just to hold onto the reins. The spread between 3-month Treasury Bills and 5-year notes has been a wild ride going from positively to negatively sloped, up and down for nearly two years (Figure 1). After the FOMC meeting the spread inverted to minus 150 basis points.

The bond market has been inverted going on for over a year, but this is unsustainable as the yield curve is naturally supposed to be positively sloped. The chairman and CEO of a regional bank headquartered in the west predicted a steeper, positively sloped yield curve was on its way because of the Treasury’s issuance plans,

“Predicting interest rates is probably a total fool’s errand…Clearly, the market is expecting…we're going to see some cuts in the Fed funds rate in '24…I think ultimately, there's real risk that term rates rise. I just don't know how you reconcile some of the pressures that we're going to see on the Federal debts and deficits, trillions dollars of interest cost coming on and probably over the next decade…I think we may end up with something like a more normally shaped yield curve. We get a lower short end and some slope to it.”

The president, chairman, and CEO of a large regional bank in the east agreed.

“Our expectation…we're going to see some cuts towards the end of next year and perhaps into the year after. I think you're going to end up seeing a much flatter if not positive sloped yield curve with some term premium, just given I think inflation will be a bit sticky and I think the issuance calendar for the government is heavy.”

Figure 1: 3-Month-5-Year Treasury Spread: Weekly Average

But the Fed has been deaf to consensus pleas that it should cut soon and often, and remains implacably focused on its sacred mission, to put the inflation genie back in its 2% bottle no matter what. And even if that mission remains unfinished, lagged, or whatever right now, the Fed cannot sit and do nothing and still be the Fed. Now is not the time to go wobbly, channeling the late Margaret Thatcher who told George Bush during the Gulf War 33 years ago to remain forceful. Powell continued,

“The forcefulness of our response to inflation also helped maintain the Fed's hard-won credibility, ensuring that the public's expectations of future inflation remain well-anchored.”

There it is. The point of the Fed’s policy is not to fight inflation or to save the economy however much that is its stated goal. It is to save its credibility. Keeping rates higher for longer, ignoring consensus expectations by eminent and well-paid professional economists that it will cut them in 2024, by the second half if not sooner, and keeping them high until the mission is accomplished, is all about credibility.

Because the Fed knows that trust, like the trust that the board of directors had in bank treasurers to know what they were doing when they said that they had their bank’s interest rate and liquidity risk under control, which evaporated last spring when they proved otherwise, is all but impossible to recover once lost. So, they will hike rates if they need to, and remain skeptical that inflation is below 2% until shown otherwise. Even if every pause has been followed by cuts, this time could very well be different. Forget hand in hand. The Fed is surgically connected to credibility, joined at the hip.

And as if to drive that point home with a vengeance, over the Thanksgiving Weekend, just days before Powell spoke at Spelman College, the Central Bank of the Republic of Turkey raised its benchmark one-week repo rate by 500 basis points, to 40%. And still inflation rages on there at 62% as of last month. And people complain about the Fed holding the Fed funds target rate at 5.25% to 5.50%.

Thus, the Fed is understandably cautious. Sure, there is a legitimate concern that, just like it waited too long to hike rates, it will wait too long to cut them, or that it has raised rates too high or not high enough. Bottom line, the Fed is uncertain, even about the timing for the first cut or even if there will be a cut. One thing for sure, though. Don’t bet on one anytime soon. Mr. Powell continued,

“Having come so far so quickly, the FOMC is moving forward carefully, as the risks of under- and over-tightening are becoming more balanced. The FOMC is strongly committed to bringing inflation down to 2 percent over time, and to keeping policy restrictive until we are confident that inflation is on a path to that objective. It would be premature to conclude with confidence that we have achieved a sufficiently restrictive stance, or to speculate on when policy might ease. We are prepared to tighten policy further if it becomes appropriate to do so.”

The FOMC does not listen to economic consensus. Bank treasurers should not, either, though the CEO and chairman of a regional bank based in the northeast clearly believed rate relief was coming in 2024,

“I think the good news is that it appears the Fed is done and that the Fed will be cutting as we get into next year.”

The CFO from a regional bank headquartered in the southeast thought that the market is ahead of itself on rate cut expectations, but only by a half-year,

“I think the market is a little ahead of itself in terms of pricing in cuts to the Fed funds rate. We're more in the perhaps second half of next year camp.”

But the chairman, president, and CEO of a regional bank in the east was not so sure about rate cuts next year and did not completely agree with his bank’s official forecast,

“Our official forecast assumes that we'll get a slowdown and even a mild recession into the first half of next year. I'm not so sure…I'm not so sure we're going to see labor get to 5% unemployment, but that's my view…I think the Fed is close to having pulled this off. I think they're done. I think they're going to stay there for a long period of time because I think inflation is going to be sticky. And absent a real problem in the economy, there's no reason for them to cut.”

The CFO from a regional bank in the Midwest also doubted his bank’s official forecast,

“The central set of forecasting scenarios that I look at are bound at the low end by the forward yield curve, which, at least as of yesterday, had one cut in April or May for four cumulative cuts in 2024. Personally, I don't believe that's going to come to pass, and we would very likely take the over on that in the near term.”

The forward curve is the default base case for bank treasury budgets in 2024 because, ultimately, you must use something, the chairman, president, and CEO of a regional bank based in the southeast told analysts,

“We have used the forward curve…I think it's got implied in that forward curve, four rate cuts pretty much over the course of 2024. So, we've used that. I personally don't think the Fed cuts that much in 2024, but that's -- we got to use something, so that's what we've used.”

But, as the chairman, president, and CEO of another regional bank in the southeast said, he does not believe in the forwards and so,

“We did a flat rate scenario, number one, because I don't believe the forward curve.”

And what if a 5.25%-5.50% range on Fed funds is neither restrictive nor nonrestrictive but just the right balance between the interests of borrowers and savers? Economic consensus does not think so, but so what? What if the target Fed funds rate is, like Baby Bear’s porridge, neither too hot nor too cold but just right and this level is the new normal? Bank treasurers should not be surprised, even if they would really like to see some rate cuts if only to do some of their own cutting on their deposit rates that in their view are kind of killing their NIMs.

What surprises bank treasurers? The chairman, president, and CEO of a regional bank based in on the east coast admitted he was surprised by the Fed, by the behavior of his depositors, and by the strength of the economy,

“What surprises me over the last 6 months? I think -- look, we've been surprised by the speed and amount that the Fed went, which in turn caused the deposit mix to shift from noninterest-bearing to interest-bearing faster than we thought...I think everybody has been surprised by the strength of the consumer and the underlying strength of the economy.”

Bank treasurers must resolve to prepare for everything. As the chairman and CEO of a regional bank based in the west that weathered the storm in the wake of the bank failures last spring told analysts,

“We came to appreciate the importance of planning and preparation…It made us appreciate the importance of refocusing on smaller businesses, middle market, smaller middle-market kinds of businesses, of operating accounts, the granularity of the deposit base became really important, and the value of it becomes clearer as you go through an experience like this.”

In fact, that should be one of their resolutions, to not be surprised by anything anymore when it comes to the economic-regulatory-financial space in which they operate. If there is one lesson bank treasurers can learn from the events of the last year it is that what can seem like an extreme tail risk can be more probable than expected, and worst-case scenarios not even close to worst case. As Jonathan McKernan, a member of the FDIC Board of Directors, admitted at an ISDA conference this month speaking about the events last spring,

“One lesson of the financial crisis was that the value-at-risk measure, which had been designed to measure the risk of short-term fluctuations in market prices, did not appropriately capitalize low probability tail events, market liquidity risk, or credit risk and, more generally, was not calibrated to a period of significant stress.”

The severely adverse scenario from the 2023 Comprehensive Capital Analysis and Review that SVB had evaded before it failed had the economy tanking and interest rates going back to 0%. If only that had happened, the bank would still be in business. In fact, its accident-waiting-to-happen treasury staff might have looked like geniuses if that scenario had come to pass. Bank treasurers must prepare for anything, and live by the motto to expect the worst, and get pleasantly surprised if they are wrong. After all, who expected that economists would still be talking about the soft-landing recession that should have been well past into recovery by now?

Which is why it should come as no surprise to them that bank supervisors are making a big show to tighten bank regulations. As with monetary policy, the mission is to preserve the public’s confidence in the stability of the financial system, even if the prescription requiring higher capital has nothing to do with the problems it ran into last spring. Supervisors intend to raise capital requirements on the largest banks even at the risk of alienating the shareholders who make the industry viable as a banking system that is publicly held and privately owned. How can “they” do that? Do not be surprised. Nor should bank treasurers at smaller institutions be surprised when bank examiners ask them to plan for liquidity stress tests which today only the largest banks are forced to follow.

The lesson that bank supervisors learned was that their gold-plated capital rules are not high enough. More is always better when they talk about regulatory capital. Speaking at the ECB forum on bank supervision in Germany, while Chairman Powell and his assembled guests sat 4,500 miles away by a fireplace at Spelman College in Georgia, Michael Barr, the Fed’s Vice-Chair of Bank Supervision delivered his remarks with certainty. Now, never mind that capital had nothing to do with bank failures and that bank supervisors did not see them coming,

“Despite their compliance with our capital rules, these banks lacked enough capital to reassure uninsured depositors that they had sufficient resources to weather this liquidity storm.….”

There is a lot to unpack in this snippet. How much capital is enough to reassure the uninsured? Here is a point worth considering. SVB had a lot of capital when it failed. This is a true statement!

Even counting the negative accumulated other comprehensive income (AOCI) that goes into the calculation of the tangible common equity (TCE) ratio which must be over 0% for the FHLBs to extend a new advance, even by that restrictive yardstick, SVB had enough capital to be considered solid. According to its last financial statement, the TCE ratio at its holding company was 5.6%, and was 7.3% at the bank level.

That does not sound like much but remember, SVB was a bank where most of its earning assets were AAA securities. A 5%-7% TCE ratio for SVB, a level that might be considered okay but nothing great for other banks where earning assets are mostly consumer and commercial loans, was very strong by any existing or proposed standard. And the accounting for the unrealized loss in its available-for-sale (AFS) portfolio was just accounting, make no mistake.

There was no impact on capital from its restructuring announcement on March 8th, except to realize the cumulative unrealized comprehensive income included in stockholders’ equity. Thus, all that happened was that the loss on its bonds was moved out of comprehensive income through the income statement and into the retained earnings account, another component of stockholders’ equity. This is just basic accounting. In fact, its regulatory capital ratio improved 15 basis points because of the sale of the AFS book, even without the capital raise it was never able to complete before it failed.

Let’s not forget that Signature Bank and First Republic were also well capitalized. But bank treasurers know they are beating a dead horse. Higher capital requirements are coming, as the chairman, CEO, and president of a regional bank based in the southeast conceded they were inevitable,

“At the end of the day, there will be more capital in the system.”

Vice-Chair Barr left that carcass and turned to another lesson that he had learned. You see, another reason that SVB failed and took along Signature and First Republic with it was that it was not prepared to get an emergency loan through the Fed’s discount window.

“While ultimately the amount of their outflows made it not possible for these banks to continue operating, these banks started from a state in which they were not sufficiently equipped to manage liquidity risk—including by being adequately prepared to tap the Federal Reserve's discount window…In the case of banks that are eligible to borrow from the Federal Reserve, discount window borrowing should be an important part of this mix.”

Just to be clear, the Fed’s discount window is not open for business overnight which was when the social media driven run on SVB’s deposit base was in full swing, nor was it open for business over the weekend when Signature failed on a Sunday. Its hours of operation are tied to the hours of operation for Fedwire. The window opens at 8:30 AM Monday morning, five business days a week and closes at 7:00 PM.

So, the fiction that SVB’s collateral mismanagement at the discount window had anything to do with why it failed is, no offense unintended, clearly ridiculous. But forget the Fed. The FHFA hammered the FHLBs in its FHLB100 report for advances they had out to SVB, Signature, First Republic, and Silvergate Bank at the time of their failure, and insisted that the FHLBs cannot act as a lender of last resort. But the FHLBs could not have saved these banks even if they had had enough wherewithal to ask for an advance in the 11th hour, because like the Fedwire and the window, FHLBs also only operate during business hours.

Shareholders should know that there is nothing to worry about. The CFO from a large regional bank based in the southwest told analysts,

“The FHLB is a very important funding source. They've played a critical role for the industry in the past, and they are going through some proposed rule changes right now. I don't expect any adverse impact from those rule changes.”

The discount window of course should be part of a bank’s contingency funding plan. But no bank treasurer is deluded enough to believe that if the bank needed an emergency loan during business hours it would still be open for business the next day. Even treasurers at non-publicly traded banks are wary of going to the discount window, a reality reflected by the paltry $2 billion balance in the Fed’s primary credit account on its $8 trillion balance sheet. But Vice-Chair Barr does not care,

“We at the Federal Reserve have been underlining the point to banks, supervisors, analysts, rating agencies, other market observers, and the public, through numerous channels, that using the discount window is not an action to be viewed negatively. Banks need to be ready and willing to use the discount window in good times and bad.”

Sorry, but in bad times, even a bank’s eligibility to borrow from the window could be questioned, as the Fed’s underwriting criteria require banks to be going concerns. SVB, Signature, and First Republic were going concerns until they were not. And in good times, banks do not need advances, much less over-priced loans from the window. In good or bad times, it is never really a good time to borrow money from the Fed no matter what it says otherwise.

But Vice-Chair Barr had another argument why banks should borrow from the Fed’s window. You see, according to him, banks need to borrow from the Fed’s window because the window’s lending rate, which is set at the top of the range for the Fed funds rate, is critical to the Fed’s conduct of monetary policy.

“The discount window is also an important tool for monetary policy. The primary credit rate, set at the top of the target range, is a component for how we can achieve rate control under a range of conditions.”

But how can that be right? Or to put it in more diplomatic terms, he is the first Fed official to ever give this context for how the Fed uses the window to conduct monetary policy. The main levers of the Fed’s monetary policy, under its ample reserve regime, are the IORB rate it pays to banks for reserves and the RRP rate it pays to money market funds for their overnight investment in the facility.

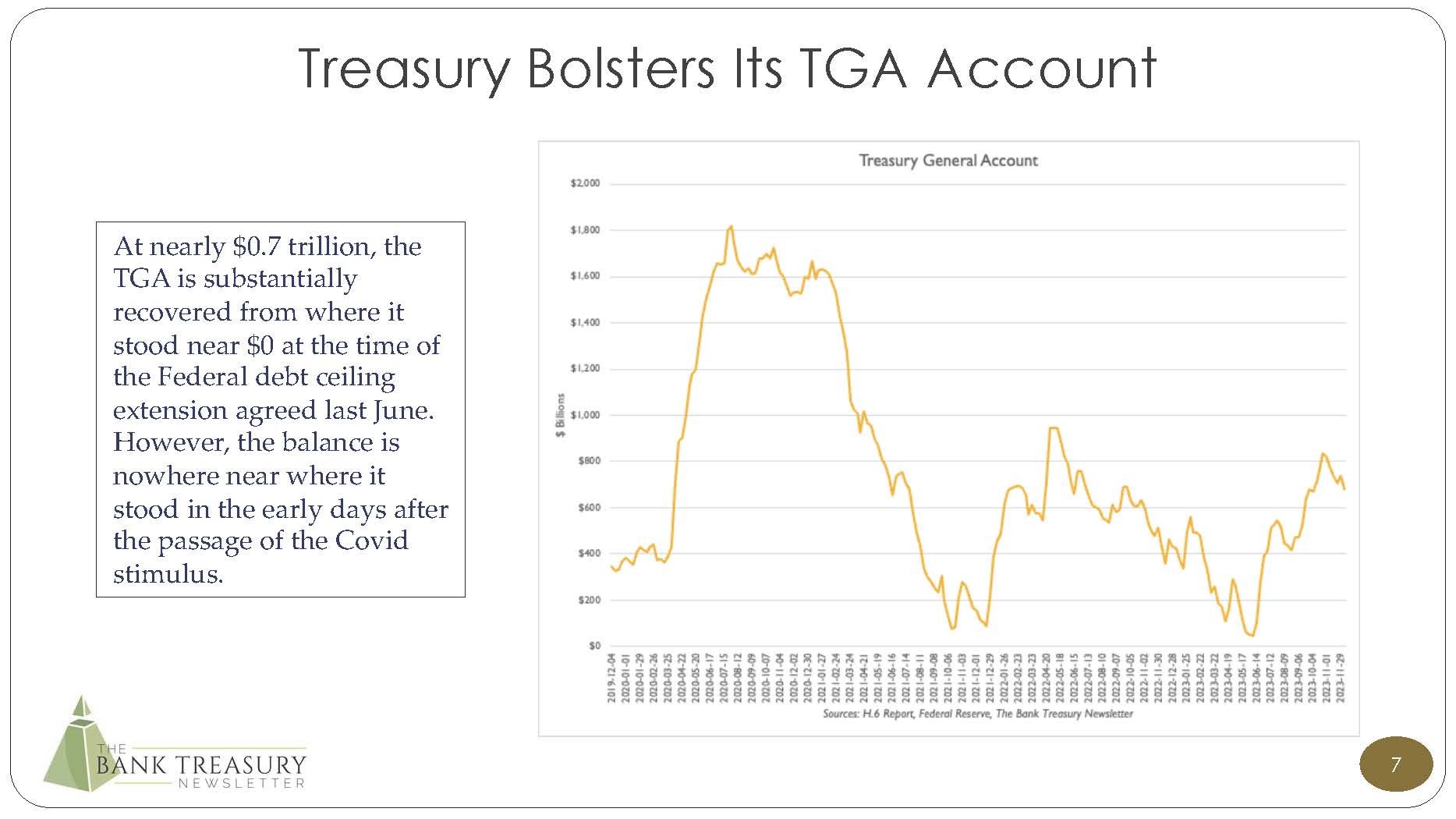

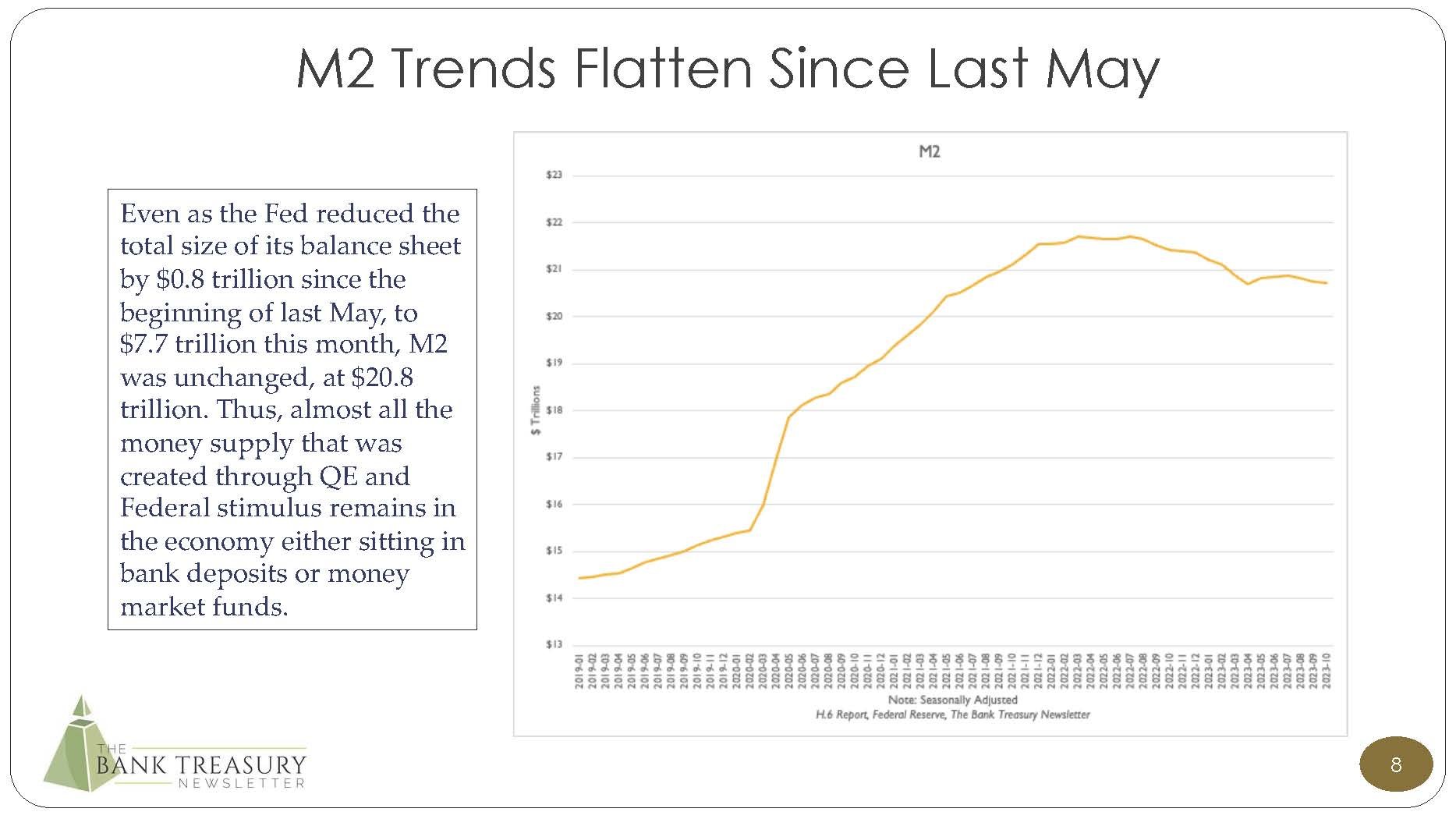

Reserves increased to $3.5 trillion this month, up from $3.1 trillion last May, while the balance of the RRP fell from $2.3 trillion to $0.8 trillion. A recent blog by the New York Fed pointed out that changes in the RRP and reserves have a ripple effect throughout the money markets, as bank deposit rates increase and draw away funds from the money market funds, which are already impacted by the Treasury’s debt issuance calendar. (Slide 13 in last month’s November 2023 chart deck illustrates the shifting trends in the Treasury’s Bill issuance since the summer.)

Now, yes, the Fed certainly has made borrowing from the discount window more attractive. The BTFP, which is a program run by the Fed through its discount window, is a perfect example of this. Start by giving it a different name. Then charge 10 basis points on the Overnight-Index Swap rate to borrow against the par value of Treasury and Agency-guaranteed securities for one year, much better terms than the 5.5% that the Fed would charge for only 90 days through its main window. Thus, with these features alone, it is no wonder the BTFP’s outstanding balance, at over $120 billion, is 60 times larger than the balance outstanding at the main window.

Ultimately, it is hard to believe that the Fed or even just Vice-Chair Barr really want banks to step up their borrowing from the discount window. If they wanted to make borrowing from the window cool, all Vice-Chair Barr and Chairman Powell need to do when they get back to the Eccles Building is to gather Janet Yellen from Treasury and all the presidents of the reserve banks into the board room. When all the Fed, Treasury, and FDIC officials arrive, invite the senior executives from all the large banks to assemble in one room and tell them that they cannot leave without first taking out a loan from the window.

Fat chance, you say! But this was exactly the approach the Fed took when it pushed the largest banks to participate in the GFC-era Troubled Asset Relief Program in 2011. Hank Paulson had a starring role! The lesson is simple. You want banks to borrow from the window? As the French say, après vous!

Another lesson from SVB was that the HTM portfolio is not the refuge from mark-to-market that bank treasurers thought it to be. SVB’s HTM portfolio was twice as large as its AFS portfolio, and the announced restructuring of its AFS portfolio triggered fears that it would also have to liquidate its HTM portfolio resulting in losses that, unlike AOCI, were not already included in its capital calculations, and that if realized could have made it technically insolvent, or near so. Moreover, given the speed at which deposits left the bank, it never would have had enough time to use the repo markets with collateral from its HTM portfolio. And it would have been expensive financing compared to the BTFP. The Secured Overnight Financing Rate (SOFR) averaged around 5.32% this month.

Time is a major friction in a contingency funding plan that counts on using the repo market to tap liquidity in a bond portfolio, whether the bonds are carried in AFS or HTM. The stress period in the Basel 3 Liquidity Coverage Ratio (LCR) is 30 days, not overnight nor even over a weekend. In today’s world where bank runs can take minutes, repo may no longer be fast enough, although trying to sell bonds from the AFS portfolio into a market panic frankly does not sound any easier. Bank treasurers should not be surprised to be offered without. Just stating the obvious, the Vice-Chair continued, saying that bank managers,

“…have also been reassessing their assumptions on the liquidity value of HTM securities, given the experiences of March.”

But here is a secret that the Vice-Chair might not be aware of that bank treasurers learn on Day 1. In an emergency, you can break the glass on the HTM account and ignore all the fire alarms that screech Tainting, Tainting, Tainting. Not that selling bonds out of HTM will be any easier than selling bonds out of AFS in a market panic. Which is why bank treasurers do not need regulators to tell them that they need to hold more cash on their balance sheets. Times are just too uncertain, a treasurer turned CFO at a regional bank in the Midwest told analysts,

“Cash levels are higher…I think over time…that's not a cash level we would look to maintain. But in this environment, until the liquidity rules come out, until we have a little more conviction on which way the economy is going, we'll continue to hold an elevated cash position and then look to right size the balance sheet over time.”

It is not just the liquidity rules and uncertainty around the economy that makes veteran bank treasurers want to hold more cash. Part of the reason is tied to uncertainty around the stability of deposits, especially uninsured deposits which proved to be the downfall of all three large banks that failed last spring. As another former treasurer, now CFO of a regional bank based on the east coast, told analysts,

“Even though the rules haven't changed from a liquidity perspective, we've taken to heart what happened back in the March, April time frame and we redid some of our internal liquidity stress scenarios. And we're looking at the nonoperating deposits that are uninsured. We're looking at different time frames of maturities and all that. And we're running with more liquidity.”

Most of that liquidity will sit at the Fed. Deposit behavior is changing through digitalization, tokenization, and programs such as FedNow and other instant payment programs. As he continued,

“We have…highly liquid assets, half…at the Fed. That's intentional, and we choose to keep that…A lot of that depends on how much is operating through the company and you want to operate with a cushion over that. We don't need to have as much as we have there, so we're being a little conservative. But I think you're going to see us always have a fair chunk there just to operate. And as the Fed Payment now system comes online, I think you want to have some flexibility and make sure you have safety there.”

The chairman, president, and CEO of a regional bank in the southeast said that his bank was sitting on more cash, even as the deposit stresses probably peaked,

“I think we probably have seen the peak, and I will stipulate…we're in a competitive marketplace and there are a lot of dynamics at play. But it does feel like the deposit betas have sort of run their cycle. And we've seen, at least through three to four weeks of repricing some of these specials that we've got the ability to price these at lower levels. And most importantly, we've had pretty good deposit growth this quarter…And it also feels like, given the lack of aggregate loan demand in the economy, the competition has moderated its deposit pricing as well…But given the liquidity in our balance sheet, we've got strong liquidity. We're holding, in our view, excess cash at the Fed. We have not really used any of our true wholesale sources of funds like the FHLB.”

You do not have to be the treasurer of a large bank to worry about liquidity, as every bank’s liquidity and interest rate risk management is coming under more scrutiny by examiners. The latest Supervision and Regulation report by the Fed discussed how examiners are stepping up the monitoring of liquidity risk management at regional and community banking organizations. And yes, there is a cost for holding more liquidity, as the CFO at a regional bank in the northeast warned,

“More liquidity doesn't necessarily impact net interest income (NII) because of the shape of the curve right now but it does dilute the margin.”

And there is a larger cost that extends beyond shareholders that will negatively impact the public and its access to banking services. In the brave new world, as bank executive after bank executive told analysts this month, businesses that do not measure up will get cut. The chairman, president, and CEO of a regional bank in the east, who was busy preparing his bank for carrying higher capital requirements and was already dealing with higher funding costs, was candid with analysts,

“I mean look, at the end of the day, everybody is reviewing their relationships. And if you can't earn a return on your equity deployed through your credit relationship against new funding costs, you shrink it.”

It is called optimization, the chairman, president, and CEO of a large regional bank in the Midwest said,

“It's always about optimizing…We have to have the discipline to redeploy that capital.”

Of course, as in the aftermath of the GFC, questions of accountability have surfaced after the crisis last March. As reported in the Bank Director, last September the FDIC released a proposed rulemaking. It would establish guidelines for banks with total assets over $10 billion and would require bank directors to assume a more “active” oversight role over the affairs of management and the bank.

In the guidelines, the FDIC insists that both the board and management “share responsibility” for the bank’s risk management, which has the potential to put board directors, pledged to support the interests of shareholders, in conflict with other responsibilities the guidelines would impose on them, to other stakeholders, including depositors, creditors, customers, and regulators. Considering the potential civil liabilities entailed in a bank director’s job, the chair of the board might soon be joining the bank’s commercial customers lamenting the difficulty of hiring and retaining people who will want a director job on a bank board.

For now, however, there will be little disagreement between the board and management how to run the bank’s interest rate risk. As the CFO of a regional bank in the Midwest told analysts, his bank employs both fair value hedges to protect against higher rates in the bond portfolio and cash flow hedges to protect against the risk of lower rates in the bank’s floating rate commercial loan book,

“Well, where rates go is anyone's guess…So, making sure we are as neutral as possible from an interest rate risk perspective and NII sensitivity is very important for us…On the investment portfolio, we want to protect against higher rates because that will ultimately impact capital levels. And so, with rates a little bit lower we added additional hedges. That would add some more asset sensitivity for us. On the other side to keep us neutral, we'll do some receive-fix swaps that will help us hedge our commercial loans…should there be a rapid decline in rates.”

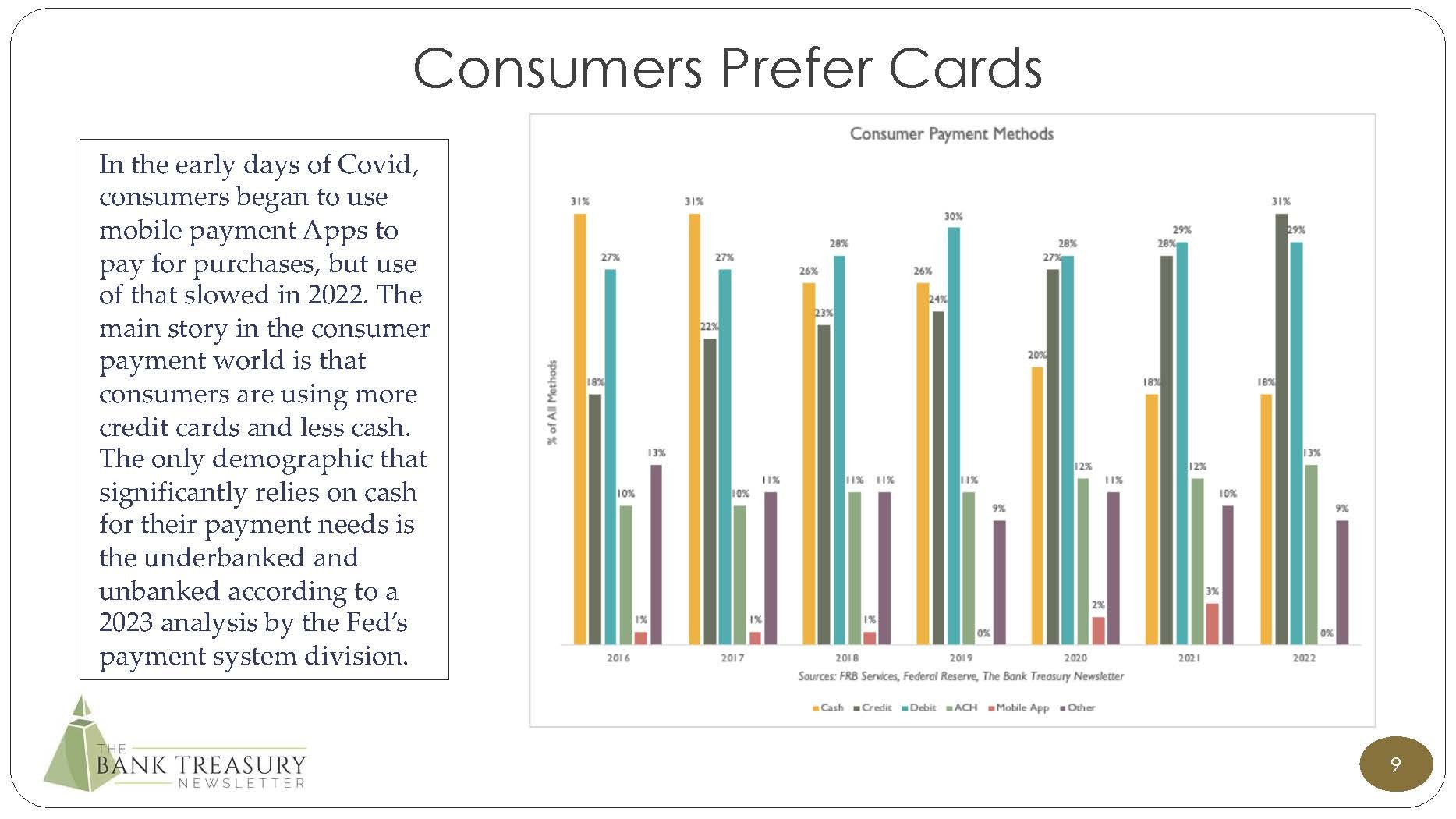

But the direction of the NIB deposits remains an unknown factor, which fell to 22% of total deposits in Q3 2023, back to where they were pre-Covid (See Slide 10 in this month’s slide deck). The CFO from a regional bank in the northeast explained to analysts why NIM and NIB were both difficult to predict,

“With NIM, the biggest risk is that noninterest bearing (NIB) percentage…Because that's…a hard equation to control because the NIB declines that we're seeing today have less to do with people searching out higher rates. It has to do with consumers predominantly using their cash and you can't stop folks from using their cash. They're getting -- feeling the impact of inflation.”

Board members are already asking him more questions, as he continued,

“We gave a preliminary plan to the Board in November. And I got -- I was getting questions from some of the directors. And one of the questions was, where are the risks in the plan that we are presenting to them. And I said the hardest thing to predict right now is the disintermediation of deposits. It seems to be slowing down but we still have demand deposit accounts shrinking, and you still have it going into sweep. You still have your CD book growing. It is hard to predict when that's going to settle down and stop. Really depends on the rate environment and when and if the Fed starts to lower rates.”

Which as any bank treasurer who has been listening to the Fed can tell you is not happening tomorrow and may not be for a lot longer than economic consensus or the dot plot would have them believe. Things can change quickly in the bank treasury world, but for now it is time to sit back, enjoy that warm fire, dig into that plate of holiday cookies, and say cheers. The information security training module can wait until tomorrow.

Happy holidays from the editorial team at the newsletter.

The Bank Treasury Newsletter is an independent publication that welcomes comments, suggestions, and constructive criticisms from our readers in lieu of payment. Please refer this letter to members of your staff or your peers who would benefit from receiving it, and if you haven’t yet, subscribe here.

Copyright 2023, The Bank Treasury Newsletter, All Rights Reserved.

Ethan M. Heisler, CFA

Editor-in-Chief