BANK TREASURERS SEE UFOS

Listen to an audio version of this newsletter on Apple Podcasts, Spotify, Amazon Music, Audible, or your favorite podcast platform.

The Bank Term Funding Program (BTFP) grew to $162 billion this month, a high-water mark for the emergency liquidity program that the Fed launched amid the bank crisis last March. Intended to help regional and community banks in the wake of the failure of Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) and Signature Bank, New York (SBNY), the program is being run out of the Fed’s discount window but offers substantially better terms than a discount window loan. These terms include loan proceeds based on the par, rather than the fair value of collateral, and a one-year term rate set at 10 basis points over the Overnight Indexed Swap (OIS) rate, which this month has been well below 5%. At the main window, by contrast, the Fed offers borrowers loans for up to 90 days at 5.50%, the top of its target range for Fed Funds. Additional penalties also apply.

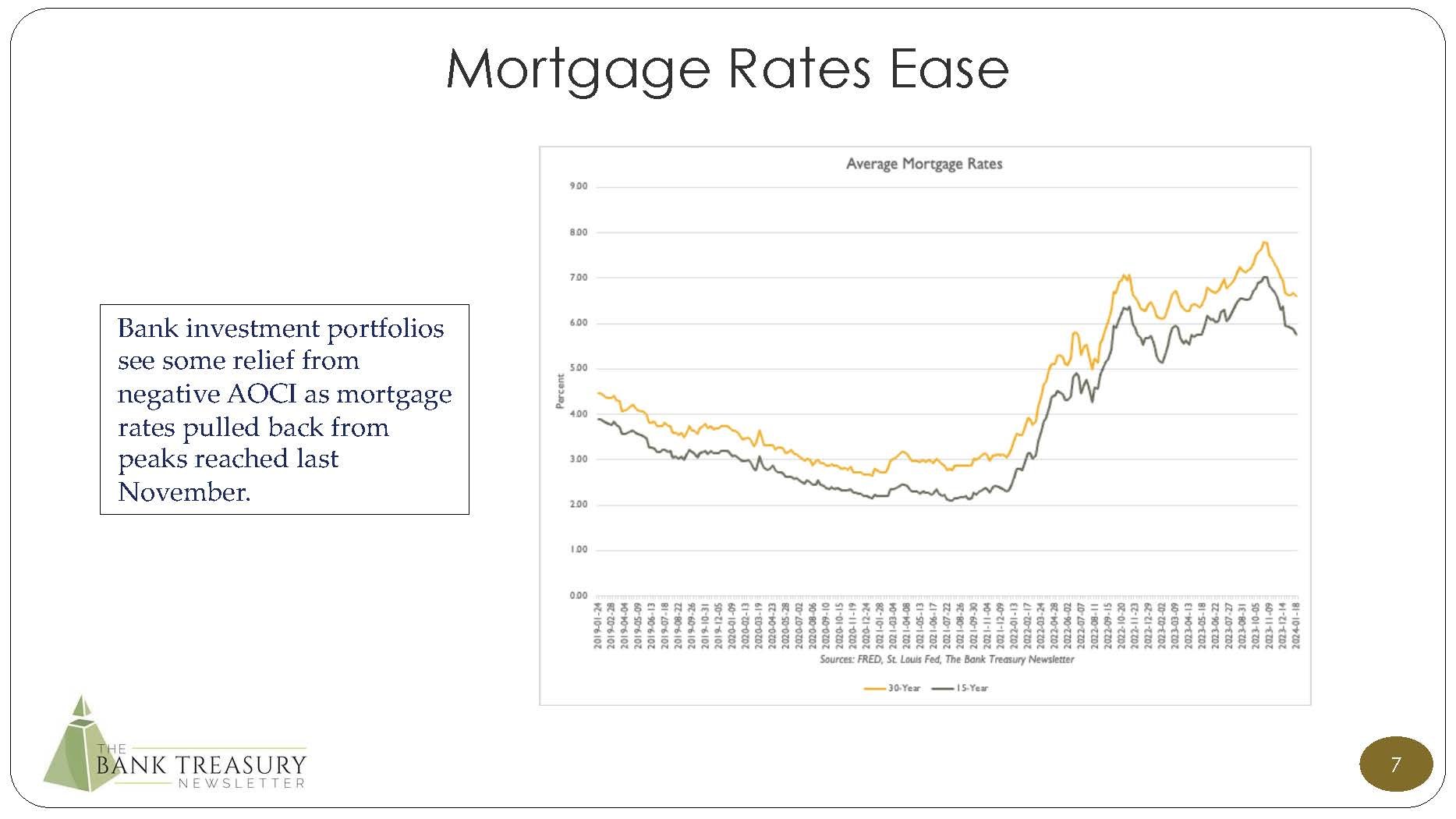

Michael Barr, the Vice-Chair of Bank Supervision, speaking this month at an event sponsored by Women in Housing & Finance, referred to the BTFP, which has been slated to expire this March, as an “emergency program” and seemed to imply by his comments that it would not be renewed. With the average 30-year mortgage rate at 6.60% this month (see Slide 7 in this month’s chart deck) down from over 7.5%, a year ago, bank investment portfolios have recovered some of the unrealized losses they sustained through the Fed’s rate hikes in 2022-23. Deposit outflows in the immediate wake of the crisis have also stabilized though trends reported in the Fed’s H.8 data are masked by the inclusion of brokered deposits which banks bulked up on last fall to replace advances. Some banks have taken advantage of the rally to restructure their bond portfolios, taking a mark-to-market loss upfront to earn it back over three years. But for others, the underwater mark on their bond portfolios has complicated their balance sheet liquidity. Taking advantage of the program before it expires, regional and community banks drew down an additional $31 billion in the last month, but the overall market stigma associated with borrowing from the Fed tempered demand. In addition, bank treasurers say that they no longer need emergency liquidity, although they could theoretically run an arbitrage between the BTFP and Interest on Reserve Balances (IORB) if they were so inclined.

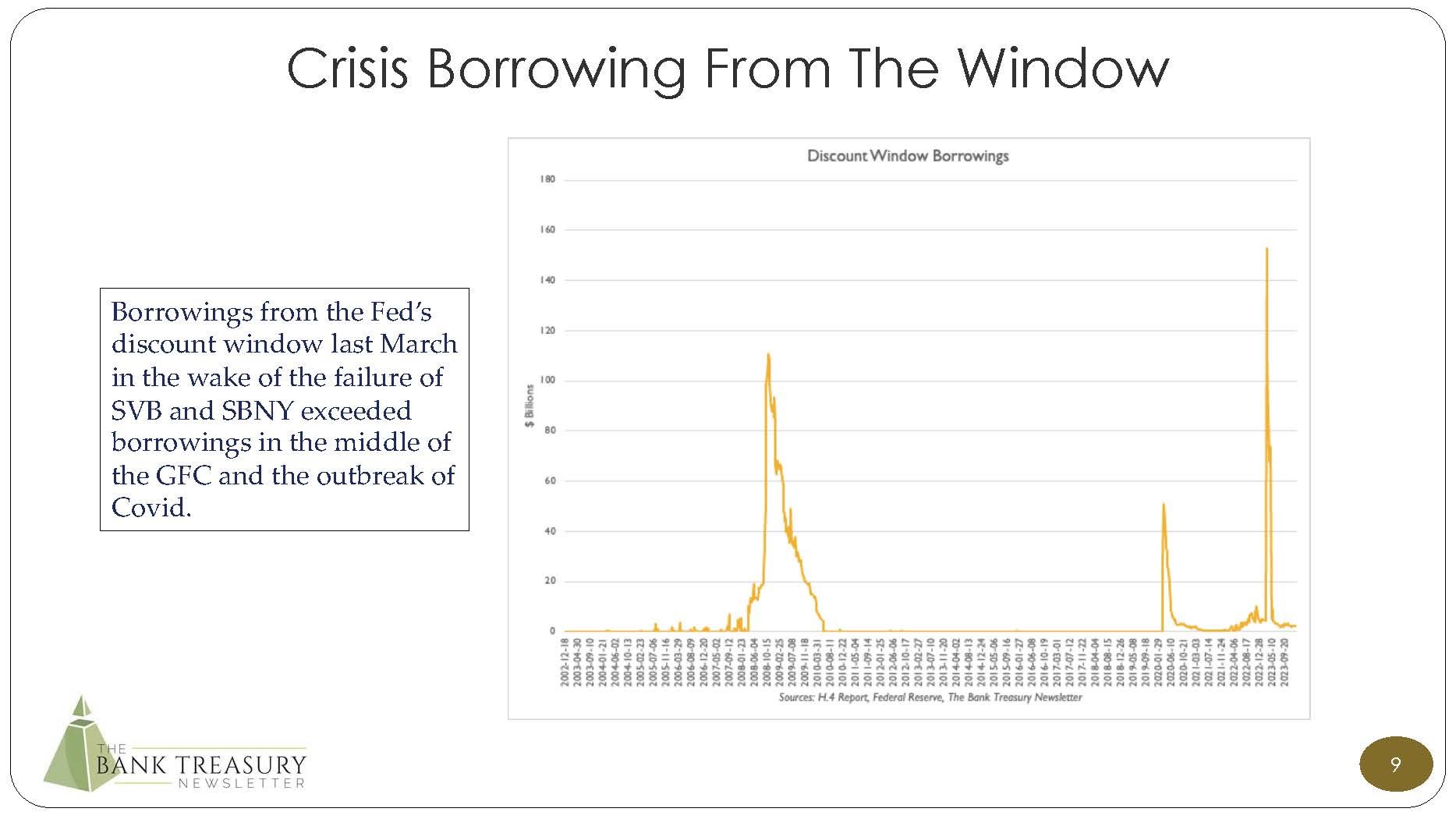

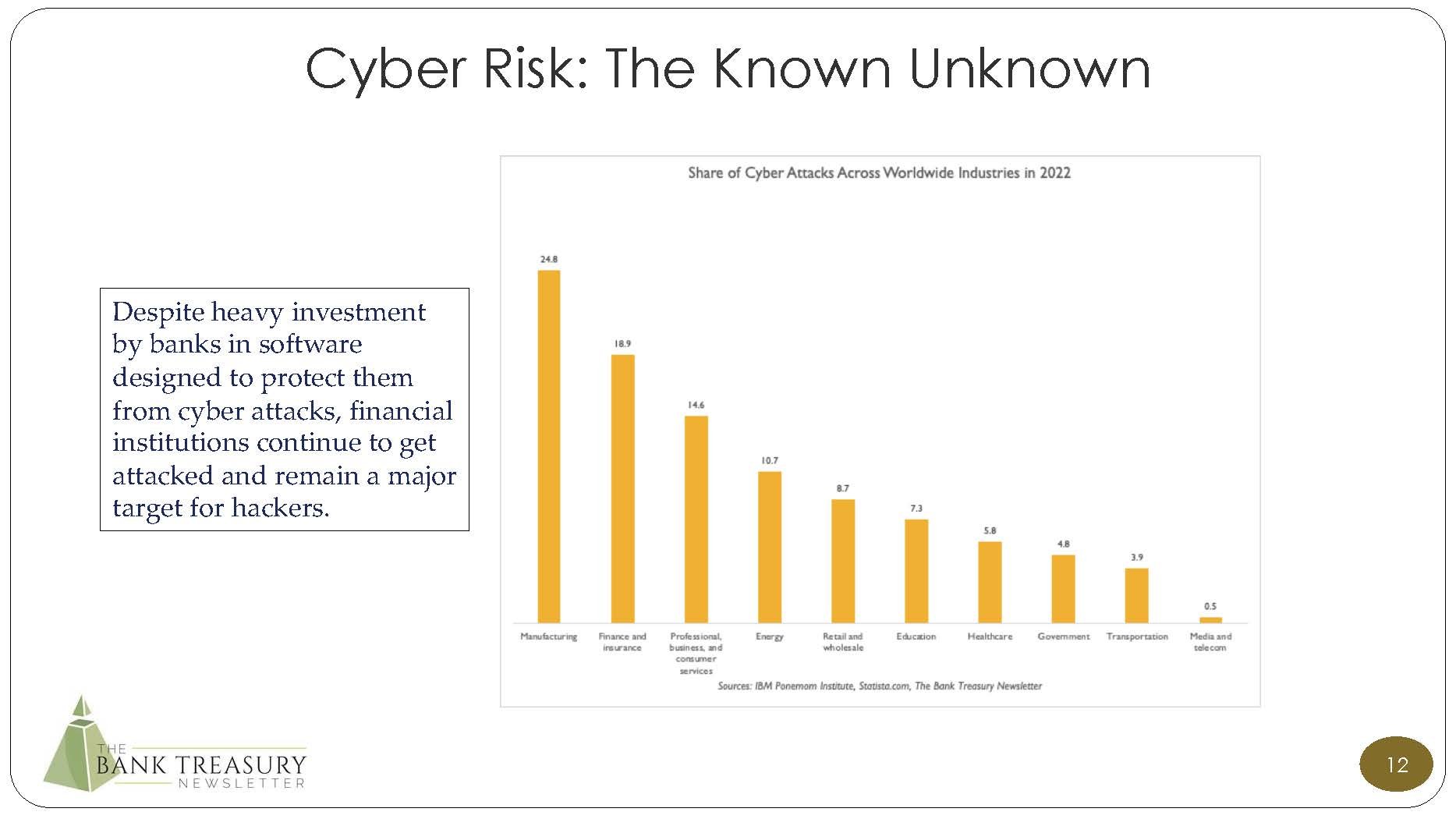

Bank supervisors believe that banks should normalize usage of the discount window in times of stress, but institutional resistance remains strong. That said, the market stigma associated with borrowing from the discount window may not be so clear-cut. In the immediate wake of the failure of SVB and SBNY last year, discount window borrowings increased from $4 billion on March 8th, to $153 billion on March 15th, suggesting that market stigma in times of market stress may not be a hindrance to banks that need an emergency loan. This month, on January 17th, discount window borrowings were down to $2 billion. The Federal Home Loan Banks (FHLBs) have been caught up in this policy debate, which had over $70 billion in advances out to SVB, SBNY, First Republic Corporation (FRC), and Silvergate Bank when they failed. The Federal Housing Finance Administration’s (FHFA) FHLB100 report published last November explicitly directed FHLBs that they may not act as a lender of last resort to banks. In a speech this month at Columbia Law School, Acting Comptroller of the Currency Michael Hsu discussed a special 5-day liquidity requirement that bank supervisors may be considering, that could help reduce some of the perceived stigma to borrow from the window. The requirement might incorporate pre-positioned discount window collateral in a liquidity ratio against certain non-operational uninsured deposits and would apply to mid-sized and large banks.

Industry lobbyists, large banks, and most of corporate America it seems continue to assail the Fed’s proposed Basel 3 Endgame capital requirements. The proposal was even the subject of a television commercial broadcast during Sunday football halftime, which is an unprecedented example of lobbying by the industry against a bank regulation, much less any Federal agency regulation. The proposal’s extended comment period has concluded this month, and bank treasurers expect that it will be revised. Treasurers at large regional banks still expect that their current right to opt out from including Accumulated Other Comprehensive Income (AOCI) in their regulatory capital calculation will end when the proposal is eventually finalized this year, however, with rate cuts on the horizon, the hit to capital may not be as much of an issue as it would have been if the proposal had been in force a year ago.

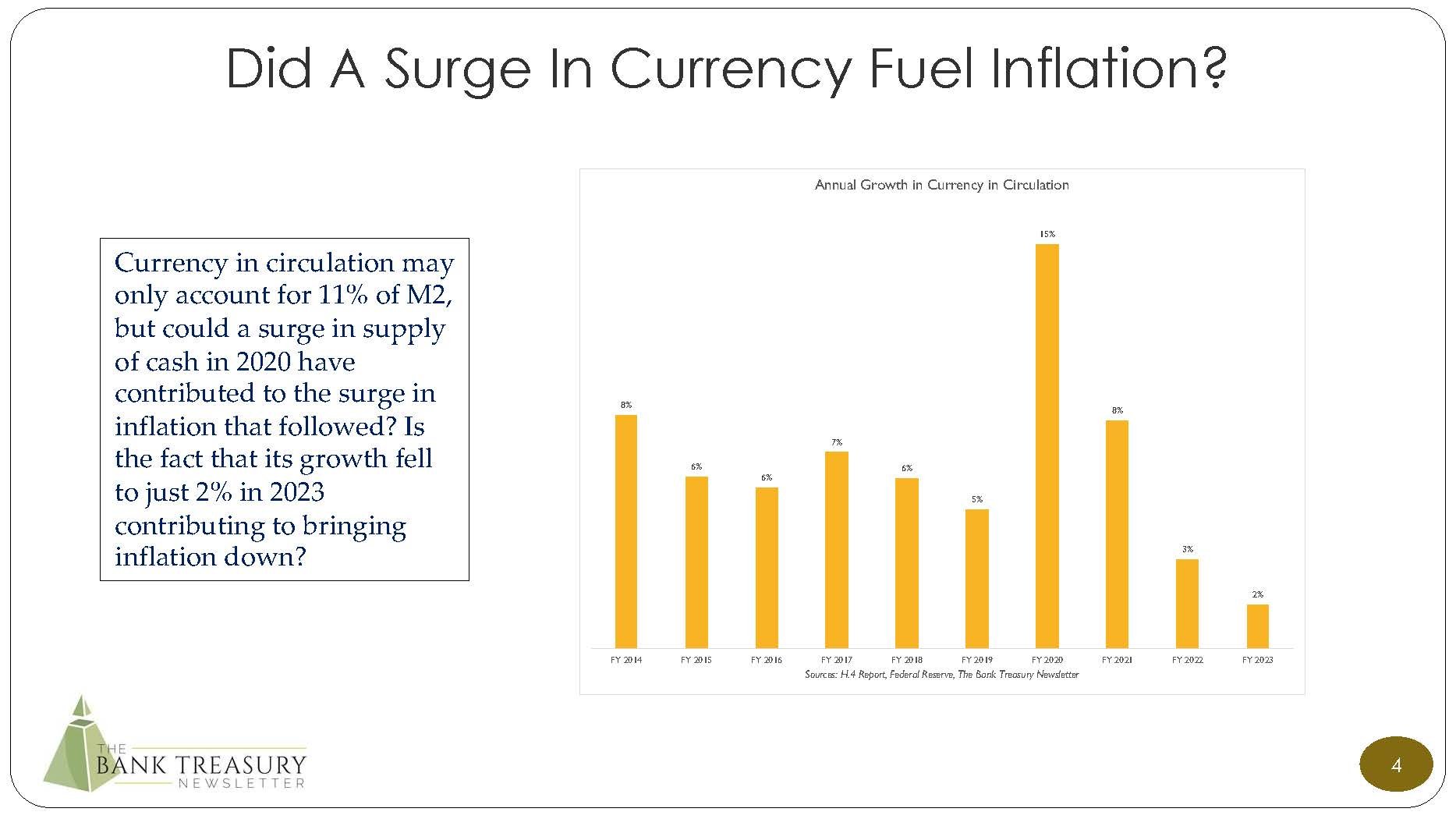

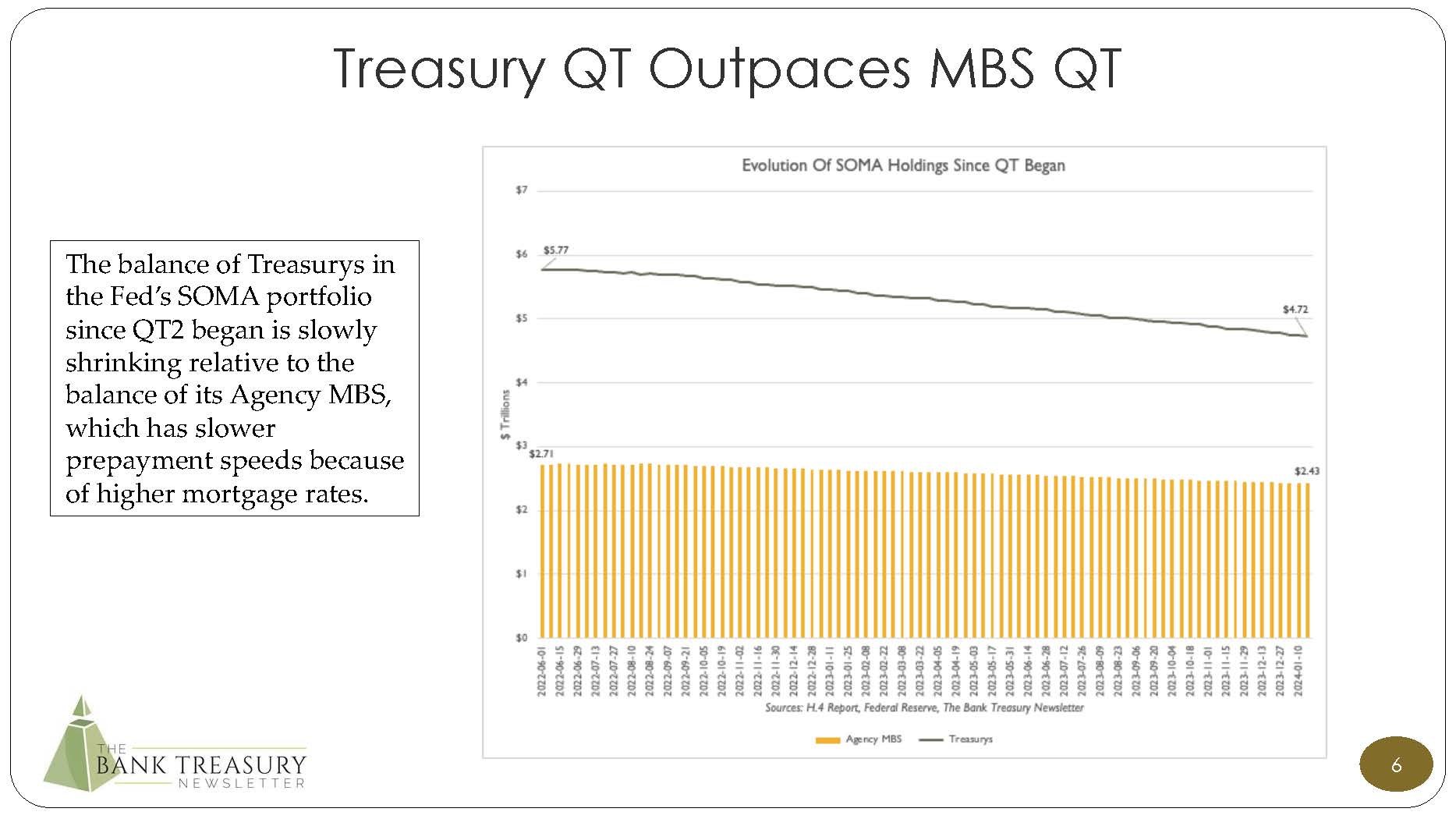

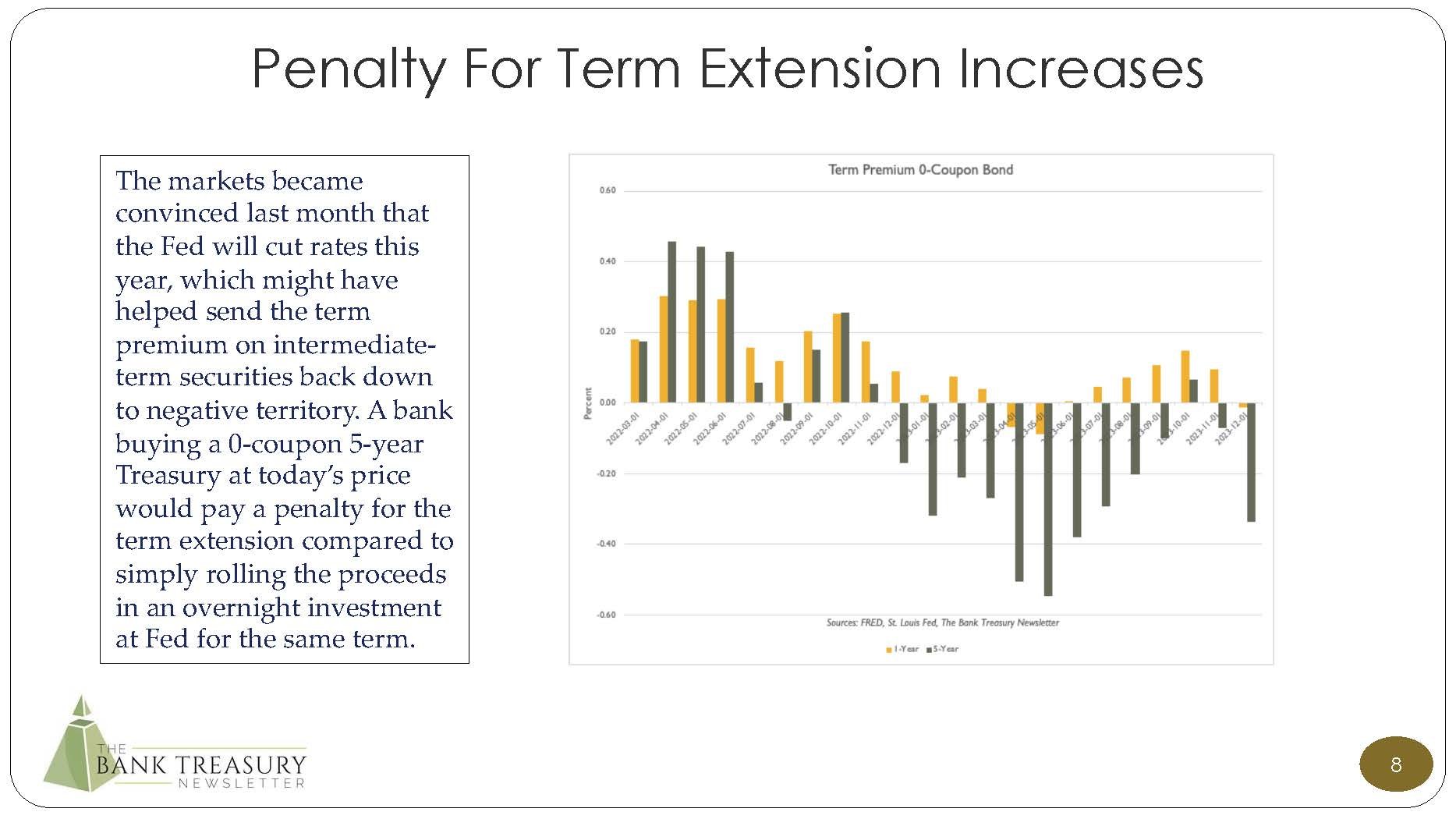

Bank managers told analysts this month that they budgeted for multiple rate cuts by the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) this year, from as many as six to as few as two, and while some hold out hope for the first rate cut to happen this March, most believe that rate cuts will not begin before H2 2024. Based on this and their assumption that credit remains stable, they expect their net interest margins (NIMs) and net interest income (NII) to reach a trough by mid-year and rebound after that, the degree of a rebound based on many factors including the number and timing of cuts. While inflation readings are still above the Fed’s 2% target and the employment picture remains robust with the December unemployment rate at just 3.7%, FOMC voters appear to view short-term rates as restrictive and are inclined to reduce rather than to increase them as soon as data supports a cut. A June 2023 study on r*, a theoretical natural risk-free rate of interest and a reference point that holds significant institutional sway with the voters at the FOMC, concluded that there was no evidence the “era of historically low estimated natural rates of interest has ended.” The FOMC not only appears to be inclined to cut rates it also appears to be inching towards an end to Quantitative Tightening (QT) and is thinking about reducing the monthly cap rates at some point.

Despite consensus expectations for rate relief in 2024, interest rate volatility as measured by the Merrill Lynch Option Volatility Estimate (MOVE) has been elevated for more than a year, the longest sustained period of high volatility since the Global Financial Crisis (GFC). To add to pressures on bank treasury, the length of the current inversion of the yield curve, which began in December 2022, is a record, with the negative spread between the 3-month and 5-year this month persisting at over 140 basis points. These factors continue to keep bank treasurers on the sidelines, holding off investing in fixed-income securities, and keeping excess deposits at the Fed. Bank reserves have held steady at $4.1 trillion since the summer as the run-off of the System Open Market Account (SOMA) portfolio, which fell to $7.2 trillion this month on January 17th from $7.7 trillion last year on May 31st has been matched by run-off in the Reverse Repo Facility (RRP), which fell from $2.3 trillion to $0.6 trillion in the same period. Bank treasurers also believe that the yield curve could bull steepen as the effect of rate cuts on the short end combines with the Treasury’s planned refunding program that will add supply on the intermediate and long end of the curve.

The Bank Treasury Newsletter January 2024

Dear Bank Treasury Subscribers,

Until recently, there was a lot of institutional resistance to coming out of the closet. Normal, decent, reliable people just do not get into such situations, much less talk about it, certainly not on the record. Throwing caution to the wind, career be damned, and confessing the wildest things could cost you your job, and your reputation, or worse, could get you banned from LinkedIn.

But hardened prejudicial attitudes are softening, and people who matter are becoming more open-minded to throwing away the script. Even people with super-serious jobs, jobs where other people’s lives are on the line, like an Air Force general, or a pilot, or an intelligence officer, perhaps an aspiring candidate for president, dare we include in this list bank treasurers, all jobs presumably where the slightest observed psychological, behavioral deviance would be enough to wreck a career, are beginning to take a chance, are willing to come out, to admit what they have known all along. Or at least suspected.

It used to be that only people wearing tinfoil hats talked about it. But this all changed in 2020, a watershed year to say the least given the Covid pandemic. But also, 2020 was when the U.S. Department of Defense—the DOD--published a memo acknowledging the authenticity of a set of videos that showed “unidentified aerial phenomena” (UAPs), recently retitled as “unidentified anomalous phenomena.” UAPs, flying somethings, which were previously known as UFOs, the latter an iconic acronym that does not need to be spelled out the way other acronyms need to be. Three letters freighted with enough pseudo-science-fictional implications that DOD officials blanched from the very thought of using them in the memo.

But call them UFOs or UAPs, the key point in the memo was that there were flying objects in the sky and the geniuses at the DOD were just as clueless as the rest of the public about what they were. And just coincidentally, sightings of UAPs, UFOs, or whatever are on the rise, as by the way are volcanic eruptions, which might have something to do with climate change. Or it might be sunspots. Or the CIA.

Because a lot has changed after Covid. Inhibitions have been fading, and conspiracy theories have proliferated and become almost respectable. Everything is connected, as bank treasurers know all too well in their world, with the Fed, rates, QT, the economy, deposits, the FHLBs, loan demand, prepayment rates, NIMs, NIIs, and all of that connected with why year after year their bonuses get lighter and lighter.

And so, 2020 was a watershed year for a lot of reasons. After the DOD memo, Congress held hearings and heard testimony from a former intelligence officer who testified that the government had an alien spacecraft and the remains of one or two extraterrestrials, as in ET phone home. The good news is that the official is no longer in government with access to sensitive information, but regardless, the testimony confirmed every conspiracy theory and spurred your editor-in-chief’s hopes for a new season of the X-Files. If nothing else, we have come a long way since Gerry Ford’s 1966 hearings on UFOs, --which for the time-line challenged was before he went on to the White House--when a government official testified that UFO sightings over the state of Michigan were all just so much swamp gas.

Plant flatulent-centered explanations aside, bank treasurers have seen their share of UFOs and UAPs in 2023, as in unexpected financial outcomes, unusual funding outflows, unfortunate negative AOCI problems, and unbalanced accounting projections. Black swans and unicorns crowd their worldview, colored as it has been by the unprecedented. Thus, the Fed raises rates to shock and awe the economic expansion, and the latter just yawns and chugs along.

In this new world, what has never happened before has happened, and now deposit runs can happen overnight. What has never mattered before now matters, as negative AOCI scares uninsured depositors who never seemed to be bothered about it before. And now, the consequences of lopsided bank accounting for assets and liabilities come starkly into view under simplistic capital measures, including the tangible common equity ratio (TCE) and book value per share.

They still are not sure what they have seen, and even now are reticent about getting on the record. Black swans are just so much swamp gas, after all, the effect of underweighted adverse probabilities that in retrospect they should have seen coming, even though no one saw SVB, SBNY, or FRC failing as fast as they did. Highly rated investment-grade institutions such that they were, even bank supervisors missed the risks these institutions were taking with their solvency and status as going concerns.

Regardless, bank treasurers are resigned to their fate, knowing full well that they will be subject to the lessons learned by their bank supervisors. Though these takeaways remain uncertain and ambiguous, they are nevertheless prejudged to the tried and true conclusion that banks need to hold more capital and more liquidity, shareholder sensibilities, and market dislocations be damned.

Bank treasurers are still dealing with these AOCI-related UFOs and UAPs in 2024, though there is reason this year for optimism, from what Fed officials have lately suggested, that from this point on, negative AOCI will recede over time. Rates are going down, not up, at least for the most part, at least as far as the geniuses at the Fed know, though so far as their insights are concerned, they remain as suspect as the conclusions of the DOD, their calls for a recession last year not lost on market participants who have good reason to suspect they have heard this all before.

But who knows, because no one seems to have a clear explanation why we are not in a recession right now, why for all the inflation eroding the consumer’s purchasing power, spending has not faltered, and why for all the worry about office vacancy, the bottom has not fallen out of the market. At least not yet. Their bonus expectations aside, bank treasurers see a Nike Swoosh in their stars and in their future when their NIMs and NIIs will all rebound, maybe as soon as in Q3 2024, and they can once again contribute to returning excess capital to impatient shareholders.

But some nightmares cannot be so easily dispelled. Even if they have seen the worst of AOCI, become more and more removed from the technical solvency and liquidity crises they faced last year with time, and have already begun to recapture negative unrealized losses in their bond portfolios, they still must contend with the effect of unreasonable anti-bank policies, the Basel 3 Endgame being just the latest iteration.

The industry and its supporters have not been shy about making their views known, penning multiple comment letters against the proposal. Sampling just one, a joint letter from the National Housing Conference, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, the National Urban League, the Mortgage Bankers Association, and the National Association of Realtors complained to the Fed last October that significant increases in capital required by the proposed Basel 3 Endgame,

“… will lead to reduced credit availability for all types of lending and undermine economic growth.”

Even some Fed officials are worried, as Fed Governor Christopher Waller said last summer,

“We must recognize that, at some point, well-intended actions to improve financial resiliency can undermine the indispensable role banks play in providing financial intermediation. In my view, the Basel III proposal crosses that line. I am concerned that today’s Basel III proposal will increase the cost of credit and impede market functioning without clear benefits to the resiliency of the financial system.”

The proposed rules will force all banks with total assets over $100 billion to capitalize AOCI, to capitalize every stupid past operational mistake they ever made, and it will hobble bank trading desks from providing market liquidity. On top of that, it will force them to issue debt, Total Loss Absorption Capacity (TLAC), that they do not need, just to recapitalize their balance sheets in the event of bankruptcy and forced FDIC receivership. Theoretically, this will solve the problem of Too Big to Fail (TBTF), even though in practice there is never enough time in a crisis to settle it using TLAC.

All the TCE in the world is not enough, because there is never enough time in a crisis to rest on capital and liquidity strength, especially in an overnight run. This is why the Fed launched the BTFP last year (which looks like it will expire as planned this March) and this is why, when Covid struck in March 2020, or when the repo market blew up in September 2019, the Fed stepped up to rescue markets even before bank treasurers had finished their morning coffee. After all, we live in real-time, cash at this very moment is what matters in an emergency, not what is on paper, the cash and equity balances reported at the end of the quarter.

Bank treasurers have been watching unregulated financial organizations invade their world for too long, and these rules, along with proposals such as the latest one by the CFPB to limit overdraft fees, and another one by the Fed to limit interchange fees, will only accelerate their forced retreat from their traditional bread and butter. While these UFOs say that they come to serve consumers more efficiently than banks can, they are just trying to turn a buck like everyone else.

Make no mistake, bankers warn, the risk to the economy from tougher rules that will ultimately help the UFO invasion at the expense of the banking industry is that at any moment UFOs could pull back from markets, tighten liquidity conditions, and wreck the economy. Is it good public policy to force banks out and to hobble their resistance with heavier risk weights, leaving what was traditional bank business in the hands of the dark shadow banks and at the tender mercy of unsupervised for-profit opportunists? Maybe yes, according to the Vice-Chair of Bank Supervision, taken aback by the intensity of the industry lobbying against the proposals that even became the subject of sports ads this year.

UFO and UAP hysteria over end times aside, there is a good reason for these measures. The public does not need to go through more stress scenarios, with March 2023 being just the latest iteration. It does not take a genius to understand that the FDIC, armed with a Deposit Insurance Fund (DIF) that equals just 1% of insured bank deposits even after all the special assessments have been collected, never mind the uninsured deposits which it ends up covering anyway, is woefully unsuited to handle major bank failures on its own.

When times get tough for big banks, the Fed and the U.S. taxpayer must step in to save the day, and policy heads want that to change. Even if in the end they will still have to intercede and rescue big banks that cannot fail however much public policy seeks the end of TBTF, there must be something at least on paper, however theoretical, that says yes, they can. And yes, the DIF is directly funded by privately owned, publicly traded banks through assessments, but the taxpayer is the ultimate backstop for the FDIC.

UFOs and UAPs have bank treasurers spooked, even the ones who do not work at big banks. Not only will the Basel 3 endgame spell end times for the capital markets, but threatening words from the FHFA that the FHLBs cannot operate as a lender of last resort to banks in need of emergency funding, or else, are going to be the death of them. Relying on their super-lien on bank collateral, the FHLBs have periodically ended up with outstanding advances on their books to a rogue list of big banks that failed, with SVB, SBNY, and FRC joining Washington Mutual and IndyMac Bank on that list. And the FDIC wants this to end, and for the FHLBs to direct members in need of an emergency loan to the Fed’s discount window.

Where presumably the Fed will refuse the loan because the discount window does not make loans to failing banks any more than the FHLBs should be doing. And yes, the FHLBs should not be put into a position where refusing an advance to a member could directly cause the member to fail. Then again, the first rule of banking is never to lend to someone who needs the money, so really, how hard is it to say no, even for a FHLB that wants to help a member in need? If a member’s only choice is an advance or failure, something serious is afoot, and its request should be viewed suspiciously.

If nothing else, if either the discount window or the FHLB are going to throw out lifelines, at least the two agencies should be coordinated. And yes, the FHLBs are a cooperative that relies on the capital markets for its funding. Their funding does not come directly from the taxpayer. Yet, with an implied guarantee from the Federal Government which is the U.S. taxpayer, they can raise relatively inexpensive funding for members, so the taxpayer has a legitimate stake in the conversation.

Like the FDIC, it will always come back to the taxpayer, for whom arguments about how the FHLBs have never lost a dime on advances to failed banks will inevitably fall flat. FHLB, FDIC, who cares, as readers of the National Enquirer, People’s Magazine, and even readers of the Wall Street Journal must think, most who probably do not even know the difference between the FDIC and the FHLB. Why are we throwing good money after bad, their elected representatives have asked and already answered. As Senator Sherrod Brown from Ohio wrote the FHFA last fall,

“The FHLBank System was created to provide liquidity to sound institutions to facilitate lending. It was not structured to be a lender of last resort – or next-to-last resort – for struggling institutions. If FHLBank members attempt to use the system as a financial backstop, it could have unintended consequences for the FHLBank System and our broader financial system.”

Of course, if the digitalization of the banking system is ever completed, if bank treasurers finally leave their analog world of posted business hours and weekend closes behind, if they then leap into the light-speed pace of 24x7, 7 days a week, into a world of not T+1 but T+0, into a banking landscape of on-demand, and overnight bank runs, it really will not matter whether the Fed’s discount window or the FHLB are lenders of last or next to last resort. Neither will be open until the Fedwire and the capital markets are open for business hours.

Bank treasurers just want to go back to the time before they first saw UFOs and UAPs and their lives changed forever. But what has been seen cannot be unseen. Recognizing that lenders of last resort may not be reliable enough in the fast-paced instantaneous payment world that the financial system is fast becoming, their regulators are considering alternatives to beef up liquidity at large banks. This will include possibly a five-day liquidity requirement where a stock of prepositioned collateral at the Fed’s discount window can be used to meet the new requirements to take the stigma out of borrowing from the window. The requirement might also incorporate some nonoperational uninsured deposit balances.

Bank treasurers see many types of UFOs when they survey their universe, unexplained financial outcomes that even if they can be explained, leave them worried, or just confused. Historical experience fails them, which is always disorienting. But even more concerning, the abnormal is becoming normal, as extreme tail events have proven to not be so extreme.

When confronted by the unexplained, the mind struggles to find a rational explanation. Well, if the economy has not cracked yet, the mind thinks, it just means that it will do so, and probably soon. Economic expansions do not last forever, after all. But they are also not human. If not this year, then next year, and if not next year, then definitely probably the year after, because rationalizations are never wrong, just early.

Economic expansions are not human, and they do not die natural deaths, but something always kills an expansion, be it the GFC that cut short the economic expansion that followed the 9/11 recession or be it the onset of Covid and the mass lockdowns in March 2020 that interrupted the expansion that followed the recovery from the GFC. If the economy does not fall to earth in 2023, it will eventually, because that is what always happens. Economists bank on the inevitable, as the late economist Herbert Stein, famously wrote,

“What economists know seems to consist entirely of a list of things that cannot go on forever. But if it can’t go on forever it will stop.”

Until it does not.

Are black swans real or just unexpected? No one expected the Fed to raise short-term rates by 525 basis points in 16 months, and no one expected that if it did, the economic expansion would just continue to chug along, albeit at a slower more tired pace, but still unstoppable, forward, and onward, seven months and counting since the last rate hike. Thus, 21 months after its first rate hike, December retail sales were better than expected and consumer confidence was up.

2023 was a year of unexpected failures and overlooked vulnerabilities. In 2024 bank treasurers see unmistakable frightening omens in their forecasts. When asked on investor calls about credit, bank management will insist that their customers are fine, credit is just normalizing, and that whoever is holding the loan on the office building with 40% occupancy that is coming up for a reset next year, is not them. But at a macro-level, when it is not about selling their own bank’s story with shareholders, they can think of many things that tell them that something is weird, to say the least. As the president and chairman of the board of one of the largest banks told a CNBC interviewer attending the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland this month,

“You have all these very powerful forces that are going to be affecting us in ’24 and ’25. Ukraine, the terrorist activity in Israel, and the Houthis in the Red Sea, QT, which I still question if we understand exactly how that works…I think it’s a mistake to assume that everything’s hunky-dory. When stock markets are up, it’s kind of like this little drug we all feel like it’s just great. But remember, we’ve had so much fiscal monetary stimulation, so I’m a little more on the cautious side.”

Fair enough, but the consensus is still calling for a soft landing, which might as well be no landing considering the FOMC’s latest projections see very full employment ahead, with the unemployment rate rising from 3.7% to just 4.1% in the next year. If this turns out to be true, then why do the market and the Fed expect lower rates? Maybe the Fed wants to pre-empt a recession with early rate cuts, but a Fed that professes that it is data-dependent would need to see something in the data flow to prompt a rate cut. It will not, or certainly should not, cut just because the public demands it, and a presidential election will only intensify suspicions that its intentions have political considerations at heart, which must be avoided at all costs.

Unsure and agnostic on the projected direction of rates, bank treasurers have positioned their balance sheets to be neutral. This is their plan so that they can feel good about their forecasts for NIM and NII, no matter what. Yet they are axed for rate cuts in 2024 because the Fed’s dot plot has said there could be three cuts and the market has as many as six. There is no use fighting the Fed or the all-knowing market. Mindful of the flaws in the forward curve’s projections, and cognizant of the dot plot’s unreliability based on their previous experience relying on its forward guidance, they still have as many as six and as few as two cuts in their 2024 budgets that they committed to on an excel sheet at the beginning of the year.

In real-time, the forward curve’s rate expectations change from moment to moment and are just as data-dependent as the Fed, so nothing is ever set in stone whether or not bank treasurers write down their rate projections on New Year’s Day. They are mere markers in the sand, made with the unstated expectation that actual results may vary. For example, the CFO of one of the global banks speaking at the beginning of the earning season this month admitted that his bank’s rate cut expectations had increased since last quarter,

“You're right, when we got together last quarter, we thought there might be three rate cuts. Now it's up to six.”

But the following day, Fed Governor Waller, dashed cold water on a March cut, and told an audience assembled at the Brooking Institute that,

“With economic activity and labor markets in good shape and inflation coming down gradually to 2%, I see no reason to move as quickly or cut as rapidly as in the past.”

And he was in the rate cut camp for this year with two cuts! The CFO of a large regional bank in the Midwest reporting after those comments were made told analysts his bank was neutrally positioned but his budget had four cuts in 2024,

“Our current projections…have four interest rate cuts by the Fed starting in the second quarter of this year. Now whether that's two cuts or six cuts, it's not going to be a material driver to our outlook. We have worked hard to get our net interest income sensitivity into a neutral position.”

Four cuts, the CFO of a large regional bank based in the southeast told analysts,

“We have four cuts baked into our guidance -- to hit the midpoint of our guidance. And we think that starts probably at the May meeting. And we know that's different than what other market participants believe, but we think that that's going to -- I think it's going to be slower versus faster. It's important to note, we're neutral to short-term rates.”

Only three cuts, the CFO of a regional bank based in the mid-Atlantic states told analysts,

“We're assuming we go with what the Fed says. We're assuming three rate cuts. The street has much more aggressive expectations than that…. We moved our asset sensitivity to neutral.”

The chairman and CEO of a regional bank in the Midwest only had three cuts, confessing that his bank had not positioned for six cuts and that more cuts could hurt,

“Well, if we bake in five or six cuts in '24, that's certainly a more challenging scenario for us, because we don't have floors in our loans set as we would like to have set for a declining rate environment. So that would be a more challenging NIM scenario for '24.”

Similarly positioned, the CFO from a large regional bank in the northeast told analysts that the bank’s NII guide was based on three cuts,

“I would say our three 25 basis point cuts would put us at the higher end of that range. If rates go maybe five cuts or six cuts maybe we will be at the lower end of that range. We've decided that over the next couple of quarters, we're going to try to move as close as possible to a neutral position.”

A series of aggressive rate cuts will cut into earnings projections, but this is all timing, as eventually, a neutrally positioned balance sheet will produce stable results, according to the CFO and treasurer of a community bank in Michigan,

“The more aggressive the rate cuts will likely cause some compression in our NIM. But one of the things that we've been working hard at, especially over the last, I would say, 12 to 18 months, is to position our balance sheet, especially on the liability side, to position for a declining interest rate environment. Some of that reduction in interest income, especially on commercial loans, will be mitigated largely by reductions in deposit costs, as well.”

Finally, the CFO of a regional community bank in New York told analysts he had budgeted for only two cuts in 2024,

“Our forecast has two rate cuts. They come in the middle to the back of the year.”

Assuming inflation gets back down to 2% this year, and that remains a big if with all the bumpy expectations by economic forecasters, and if economic growth continues to chug along regardless of the level of the Fed funds rate, the Fed believes it needs to cut rates anyway. It needs to cut rates, not because the market and the forward curve demand it, but because in the theoretical and unobservable world of risk-free rates and term structures, the current target range for the Fed Funds rate is restrictive, and a restrictive monetary policy is supposed to be temporary, not the norm.

Institutionally, r* has sway over monetary policy thinking, a hypothetical, natural risk-free rate where supply and demand for money are equal, and inflationary and deflationary tendencies are balanced. Given that even now inflation is still above the 2% target, and bank treasurers might prefer that the Fed not reverse all of the rate hikes, at least not too quickly, recent analysis by New York Fed economists suggests that r* is not any higher today than it was before Covid. In their view, we never left the Zero Interest Rate Policy (ZIRP) world when central banks even flirted with Negative Interest Rate Policy (NIRP), the UFO of its time.

Perhaps rates are restrictive, and with existing home sales at the lowest level in years, realtors in the middle of legal actions that could threaten the structure of their commissions must welcome the prospect of some rate relief. Spurred on by the prospect of lower rates, pending home sales had the biggest monthly gain since September 2021, even with the fading probability of a rate cut by this March.

But maybe the most important reason why the FOMC will cut rates is because cutting them gives the members room to raise them again, as raising them gives them room to cut them again. The same could be said for QT and Quantitative Easing. Reducing the balance sheet gives the Fed room to increase it again if needed. According to the former New York Fed president, Bill Dudley, speaking to the Financial Times last November, QT is all about the next QE. Why does the Fed need to shrink its balance sheet?

“I think basically to rebuild capacity, so you can do quantitative easing again, without taking massive interest rate risks.”

But the end of QT could be coming, with the latest minutes raising the idea that the FOMC could begin to discuss the subject and possibly reduce the caps shortly afterward, which are currently still set at $60 billion for Treasurys and $35 billion for Agency MBS.

“Several participants remarked that the Committee’s balance sheet plans indicated that it would slow and then stop the decline in the size of the balance sheet when reserve balances are somewhat above the level judged consistent with ample reserves. These participants suggested that it would be appropriate for the Committee to begin to discuss the technical factors that would guide a decision to slow the pace of runoff well before such a decision was reached to provide appropriate advance notice to the public.”

Atlanta Fed president and CEO, Raphael Bostic, who sees two rate cuts in the second half of the year, explained why the Fed would need to review its plans for QT, even if not right away,

“Today we haven’t seen any movements in money markets that suggest we’re close to a scenario where we don’t have ample reserves anymore. Clearly, at some point, there’s going to be a signal that we’re going to get closer to that threshold, and we’re going to have to do some thinking.”

The term structure of a deeply inverted yield curve is an unnatural, aberrant phenomenon in the rates world, and like all UAPs and UFOs in the bank treasury world, they just cannot last forever. But so far, its longevity has defied all expectations and experience. Inverted yield curves are generally assumed to be harbingers of recession, but a soft landing is the new consensus, as the president, chairman, and CEO of one of the large global banks told analysts,

“We think the soft landing is a core thesis and our internal data supports what our research team sees.”

But even without a recession in the forecast, an inverted yield curve is still a forecast for lower rates, backing up the economists who believe that r* is just as low as ever. And even if lower rates are still a ways off, even if the forecast is early, and a recession is out of the question, there is one takeaway that cannot be disputed. An inverted yield curve, especially one that has been as inverted for long as this one has been, is not good for the bank treasury business. The CEO and chairman of a large regional bank headquartered in the northeast reminded analysts of the costs of an inverted yield curve and how a positive curve was built into assumptions for earnings growth,

“We've had an inverted curve for a long time. So, when you think about the medium term, presumably, we get back to a point where there's a normal yield curve, which also benefits NII.”

Fund transfer pricing models and the profitable banking they support based on a positive NIM normally assume a positively sloped universe, though bank treasurers can work in any rate structure. It all comes down to flexibility and cost. But ultimately, bank treasurers want a positively sloped yield curve. With much of the banking business conducted between the short and intermediate part of the yield curve, the inversion makes it very expensive to fund intermediate-term loans at current marginal short-term rates.

As Figure 1 shows, the spread between the three-month and 5-year constant maturity Treasury rates has been inverted for more than one year, which over 40 years is the longest yield curve inversion in modern history. At the current spread, with overnight rates 140 basis points higher than intermediate spreads, a loan based on the 5-year part of the curve does not do much for shareholder value, at least at face value. If made, it better be worth it, is all that shareholders might say.

Figure 1:5-Year-3-Month Constant Maturity Spread

Unnatural as they might be inverted yield curves ultimately reflect the balance between supply and demand of money. There is $27 trillion of Treasury debt outstanding that is held by the public, two-thirds of which consists of Bills (20%), Notes (20%), and Bonds (26%), and equally, there are investors with savings to absorb and hold that supply. If there are more than double the outstanding Treasury Notes and Bonds then Bills outstanding, and rates on Notes and Bonds are 140 basis points lower than rates on Bills, even when everyone seems to be concentrated in the front end waiting for clarity from the Fed, there must be a lot more money that wants to hold Notes and Bonds than to hold Bills. At least in a world where up is up and down is down!

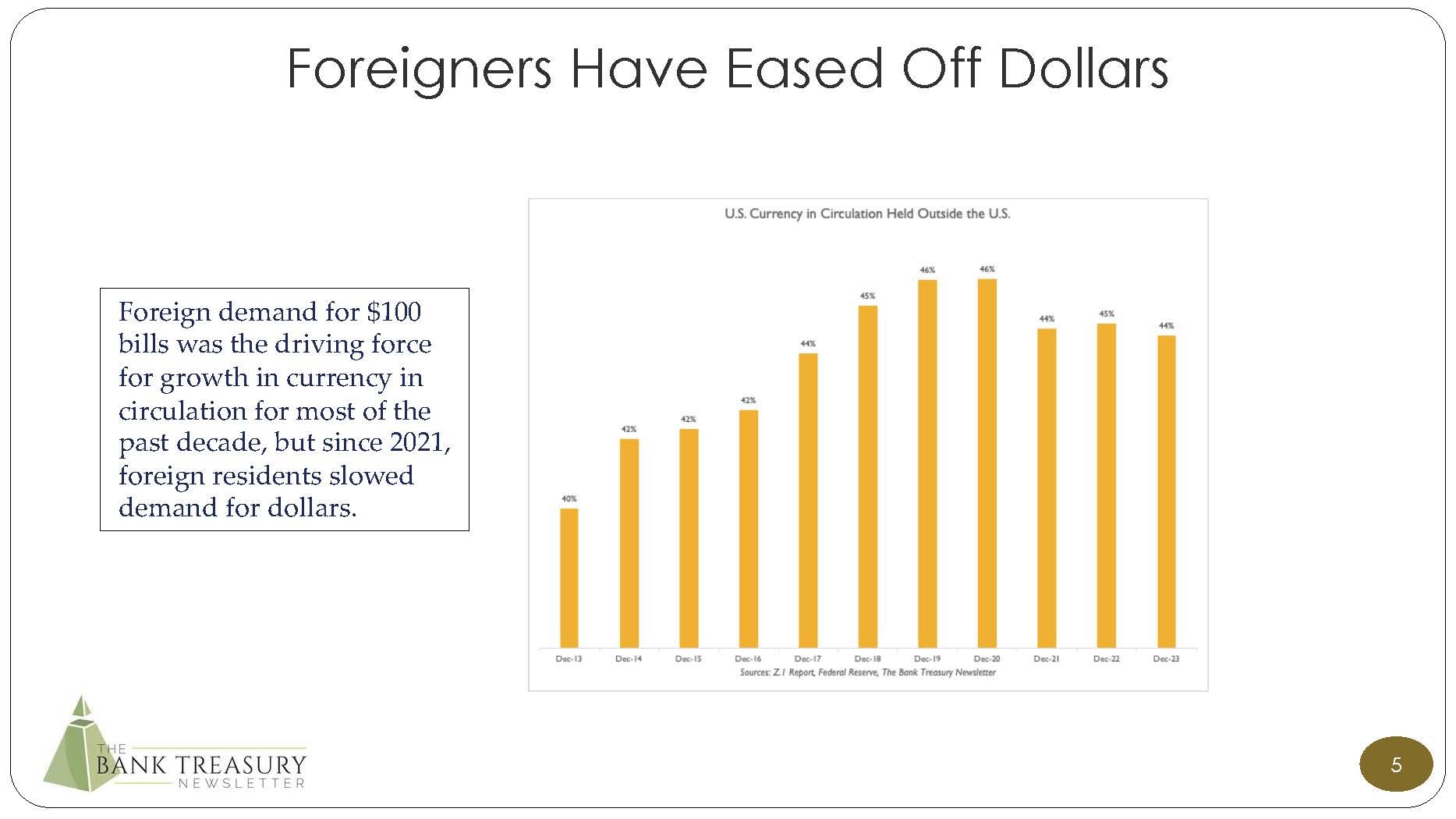

Where that money is coming from is a mystery. It certainly cannot be foreign, as foreign investment in Treasurys according to the U.S. Treasury is nominally unchanged but proportional to total outstanding Treasurys is down more than ten points from a decade ago, at 30% (Slide 5 in this month’s chart deck).

So, the mystery investors in long Treasurys remain an unknown factor on rates that bank treasurers should not ignore, especially in the face of the Treasury’s refunding plans for the year. Though the yield curve is deeply inverted now, there is a risk that it could bull steepen for 2024. If the Fed cuts short rates, the long end of the yield curve could stay anchored, as the chairman, president, and CEO of a large regional bank headquartered on the East Coast explained,

“In the near term, we think the market's got ahead of itself. I think until we're clear on the outcome, or clear on inflation and Fed actions, we're happy to stay neutral. I think my expectation is notwithstanding what the Fed does through the course of '24 with the Fed Funds rate. My expectation is you're not going to see a lot of action in the longer rate simply because of the supply calendar and the fact that inflation will have a tail and while the Fed could ease somewhat, I think inflation is still going to be running against its goal. We'll have a lot of issues. So long story short, we don't see a burning desire to put money to work here because we think that opportunity is going to remain.”

Uncertainty and volatility go hand in hand, and as the Merrill Lynch Option Volatility Estimate (MOVE) index (Figure 2) suggests, interest rate volatility remains elevated. Generally, a little volatility is good for bank treasury which sells option volatility on both sides of the balance sheet. Thus, in the bank treasury world, mortgage loans can be repaid at any time, loan disbursements can be drawn or put off, and deposits can be pulled on sight. But high volatility is bad for business.

Figure 2: MOVE Index

Volatility is tied to a lack of clarity about the Fed, and lack of clarity feeds complexity, which increases uncertainty. It is all connected. But ultimately it comes down to the Fed. Unlimited, all-knowing, and all-powerful, the Fed is a UAP, the unknown factor over markets. What is the Fed going to do on rates? It keeps its watchers guessing, and even with its guidance the differences in opinion between what the Fed thinks it is going to do and what the market thinks it is going to do, is unprecedented. As the CFO of a global bank told analysts, the only position to take in the face of so much volatility is neutral.

“If you go back 12 months…there was a disconnect between what the market thought was going to happen in '23 and what the Fed thought was going to happen in '23. The market was calling for rate cuts in June of '23, and the Fed wasn't…The year unfolded very, very differently compared to what everybody thought was going to happen…This year, again, I think the Fed and the markets are a little bit at odds. We had a Fed commentator talk a couple of days ago about March being too early. Notwithstanding that, the market thinks there's an 80% probability of a rate cut happening in March. So, we're neutrally positioned in the outlook for '24.”

The deposit picture is complex which complicates the forecasts for NIMs and NIIs. Too many rate cuts in 2024 and NIMs and NIIs could suffer, but they could also staunch the flow of deposits out of noninterest and into interest-bearing accounts, especially on the consumer side, as the CFO from a large global bank reasoned,

“If we do have rate cuts, it's going to start to dampen the appetite of people thinking of moving out of the noninterest-bearing.”

On the other hand, interest-bearing high beta deposits give bank treasurers a lever to offset lower repricing on floating rate loans, as what quickly goes up comes down just as fast. The above-quoted CFO continued,

“Over this year, there's been a move towards more interest-bearing. And that helps us if we start seeing Fed cuts because that's going to allow us to take those rates down.”

Noninterest-bearing deposits have migrated into money market accounts and CDs, but these CDs, while competition is a factor, are strategically being priced to align with rate cuts later this year when they will mature and reprice lower on the rollover. Noninterest-bearing deposit outflows, as the CFO from a large regional bank based in the southeast explained, are going into,

“…CDs and money market accounts…We must be competitive. We must watch what our competitors are doing. But we have mechanisms to start working that down. Part of that is making sure we don't go too long on our CD maturities…Our average CD term is seven months.”

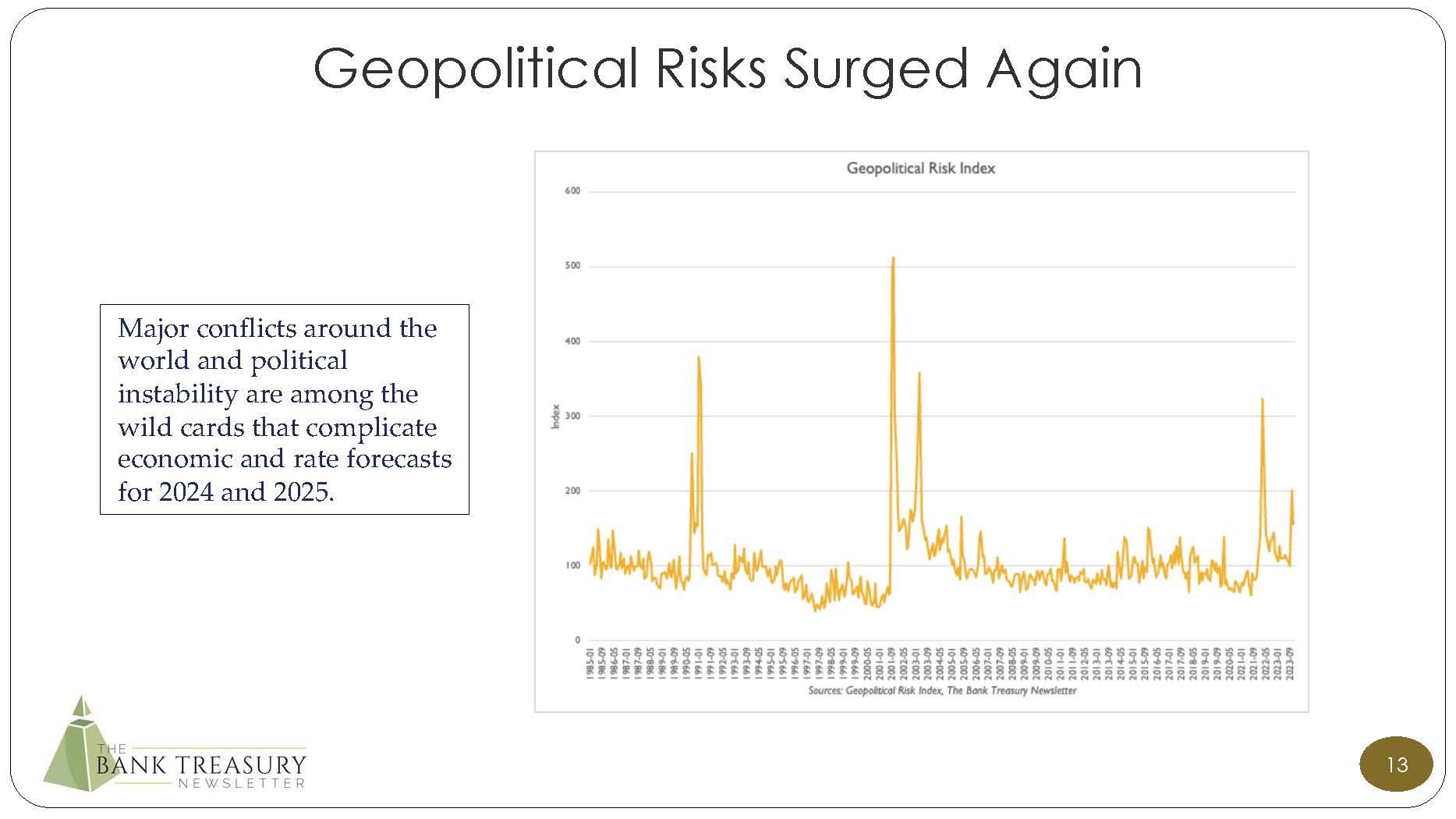

The other side of the balance sheet also contributes to the complexity involved in deposit pricing and in turn, the task of projecting NIMs and NIIs for 2024. If the Fed is higher for longer and there are no rate cuts in 2024, for example, loan demand will likely stay slow, which similarly will dampen competition for deposits. Indeed, commercial deposits are also building up as businesses hold off on investment projects until more certainty sets in around the economic and interest rate landscapes that have also been complicated by geopolitical events, from Asia, Europe, and the Middle East (see Slide 13 in the chart deck). The upcoming presidential election adds to the list of uncertainties.

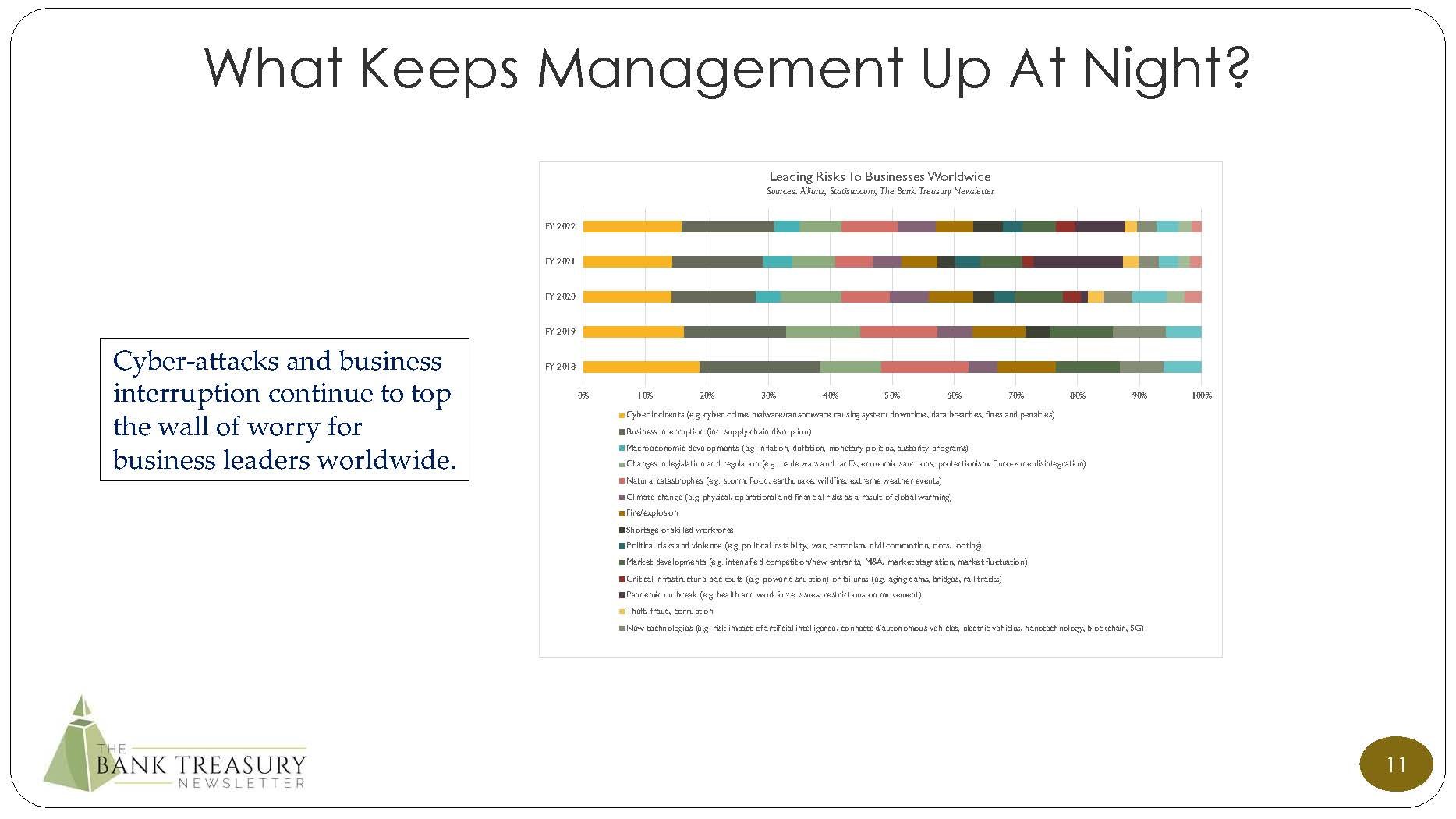

Bank treasurers cannot just rely on typical stress scenarios when they formulate balance sheet strategies. They need to see the UFOs and black swans for what they are and to be ready for them. They must consider the possibility that extreme tail events might not be so extreme, and the probability of encountering them not as low as might be thought. Like swamp gas, there might be a perfectly obvious and naturally occurring scenario when they might be encountered.

The severely adverse scenario in the Fed’s 2023 stress tests had the economy falling into a deep recession last year and interest rates going back to 0%, which for SVB would have been a dream come true. In retrospect, however, what SVB should have considered was the possibility of a black swan in its future, something it had never seen before or knew existed, a scenario where the exact opposite of the severely adverse scenario occurs, and they fail overnight. As bank treasurers learn in Bank Treasury 101, rule number one when handling risk is to expect the unexpected.

The Bank Treasury Newsletter is an independent publication that welcomes comments, suggestions, and constructive criticisms from our readers in lieu of payment. Please refer this letter to members of your staff or your peers who would benefit from receiving it, and if you haven’t yet, subscribe here.

Copyright 2024, The Bank Treasury Newsletter, All Rights Reserved.

Ethan M. Heisler, CFA

Editor-in-Chief