BANK TREASURERS ARE WONKS

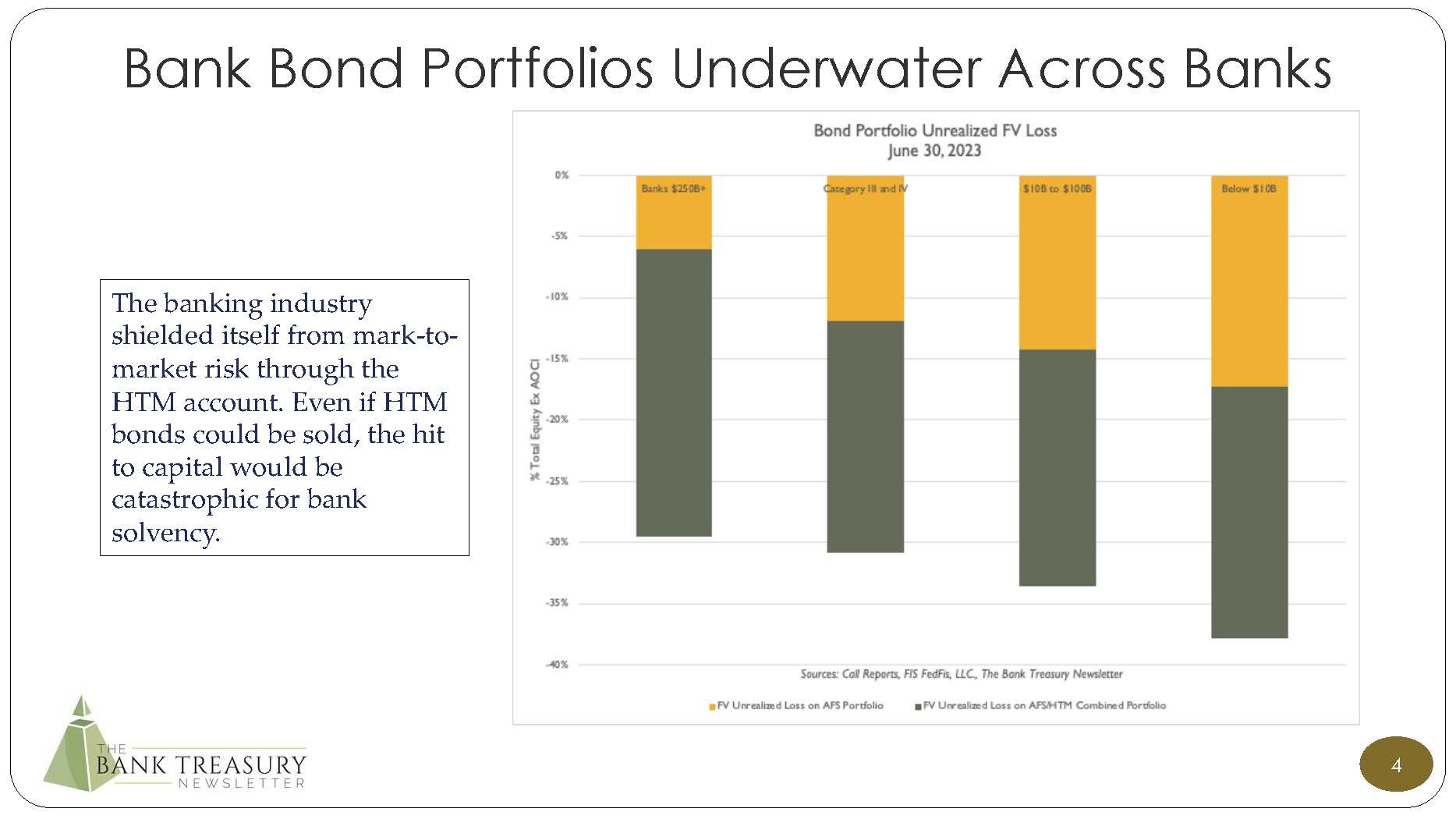

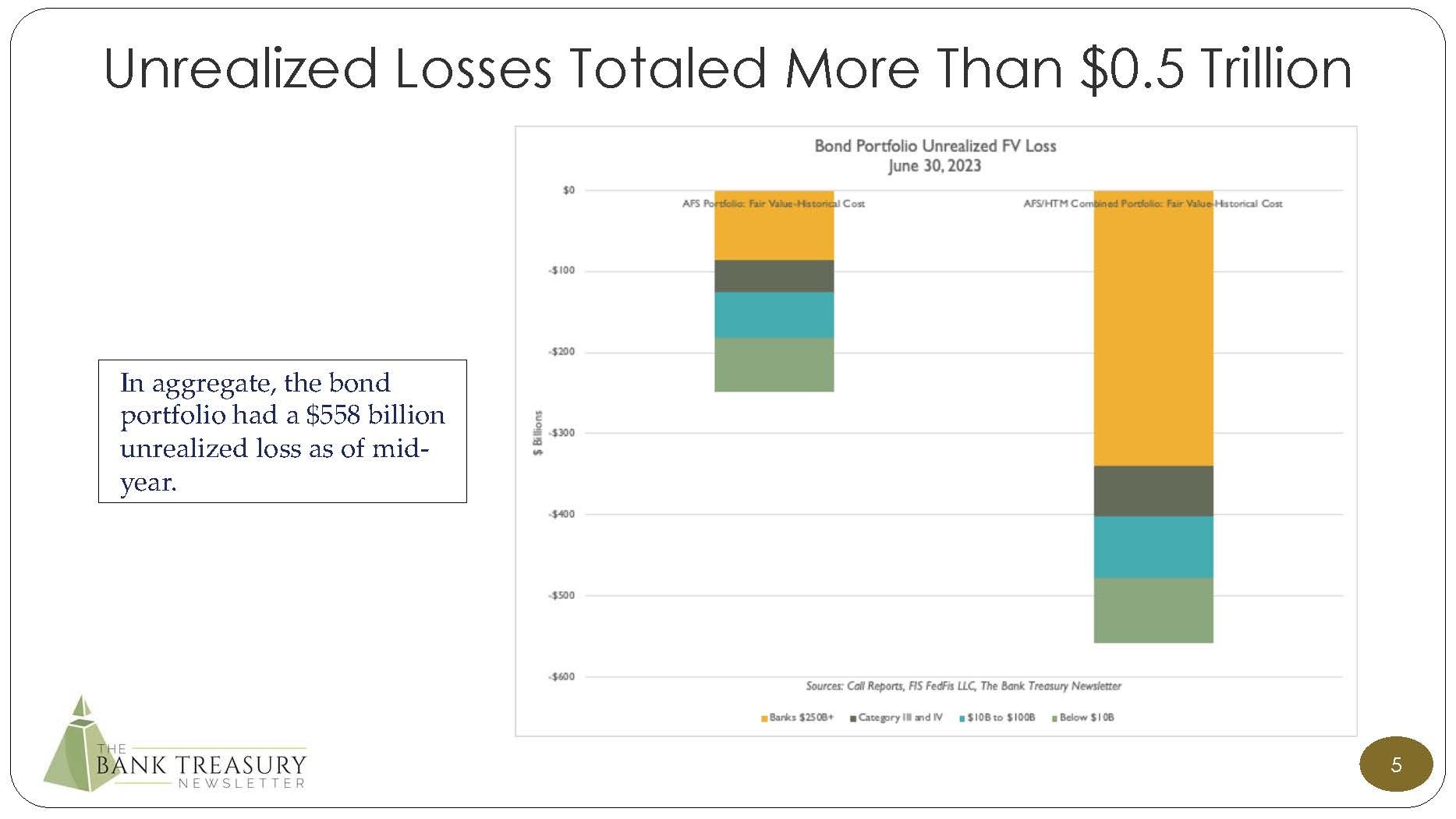

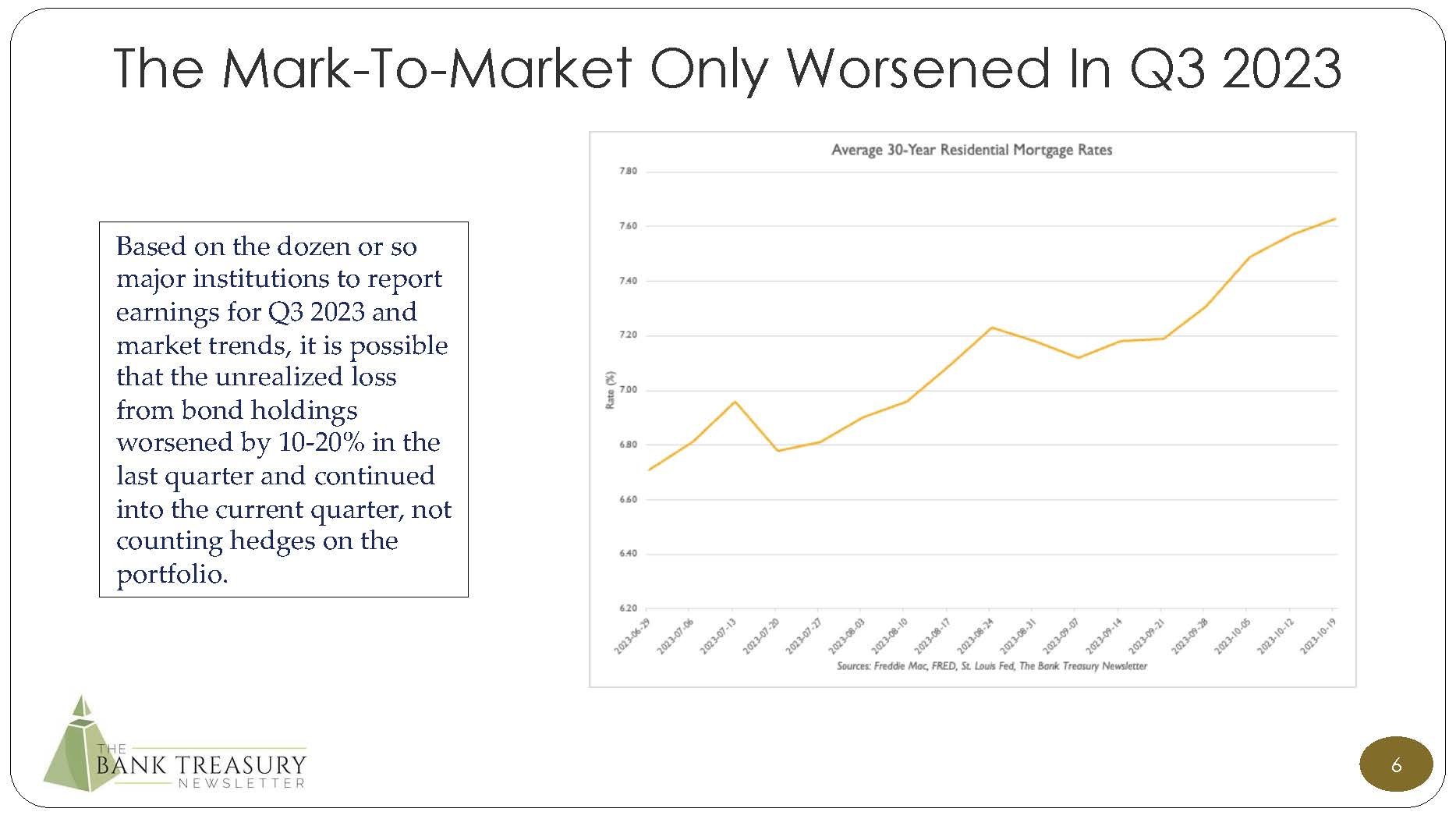

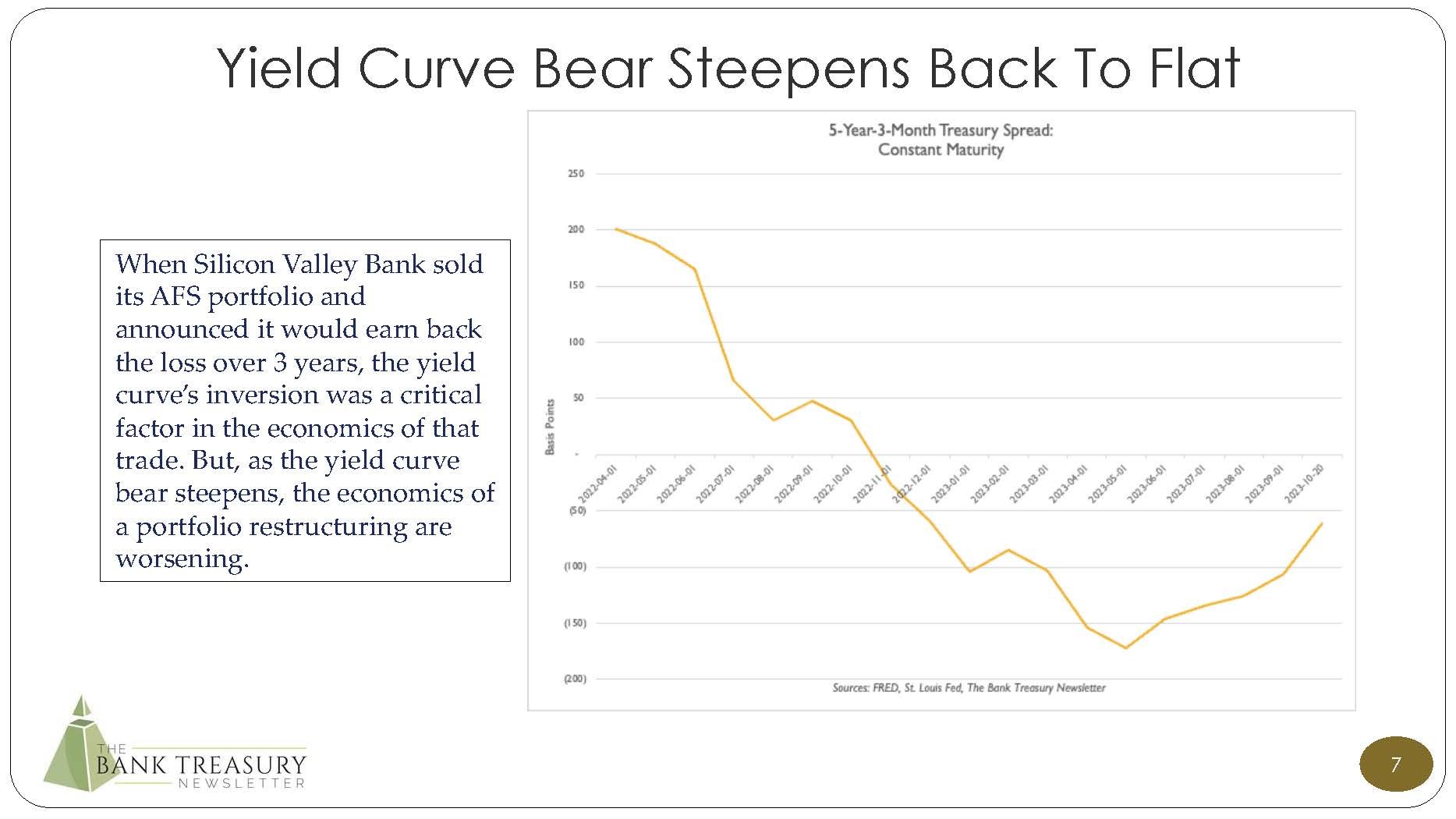

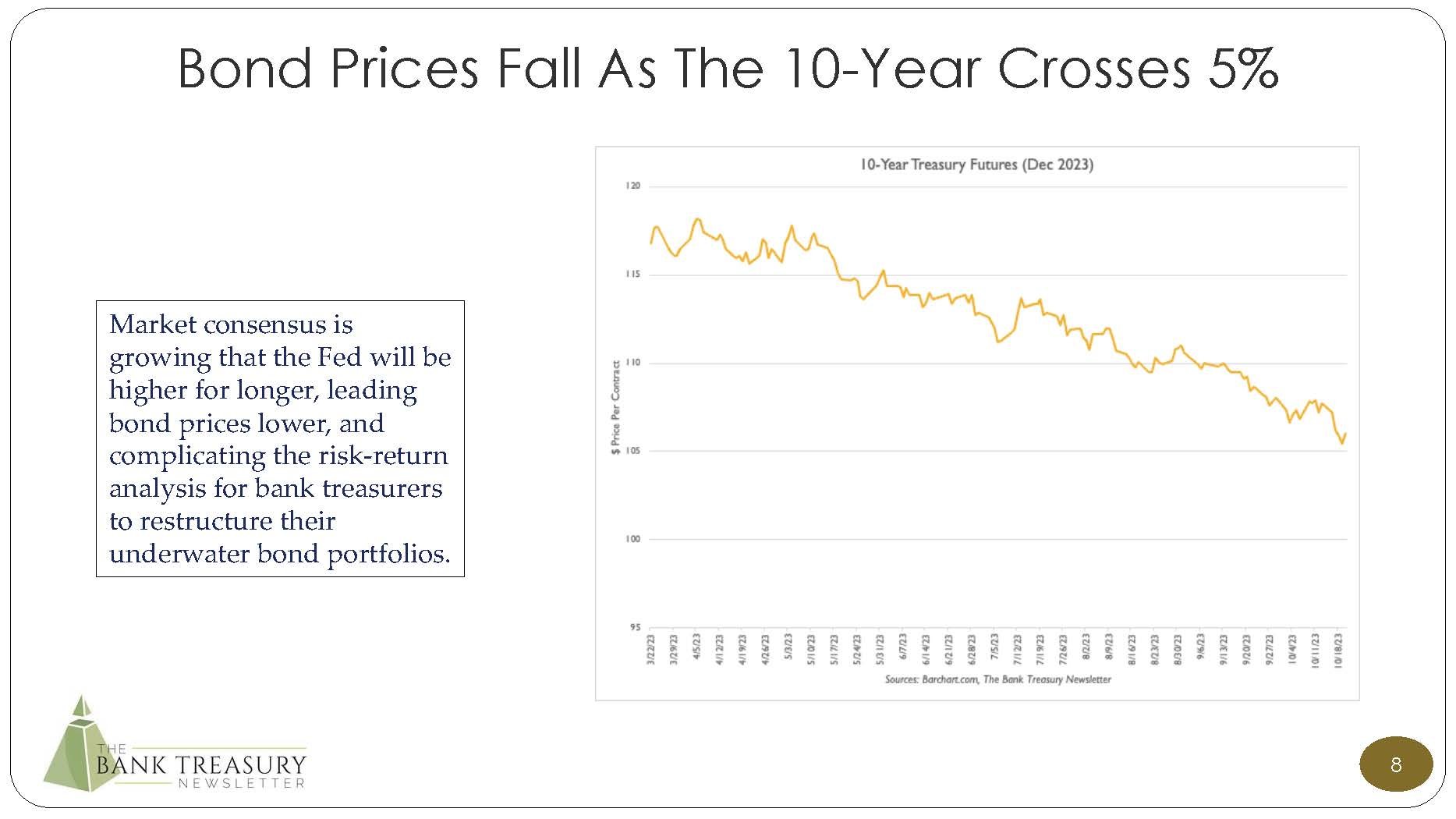

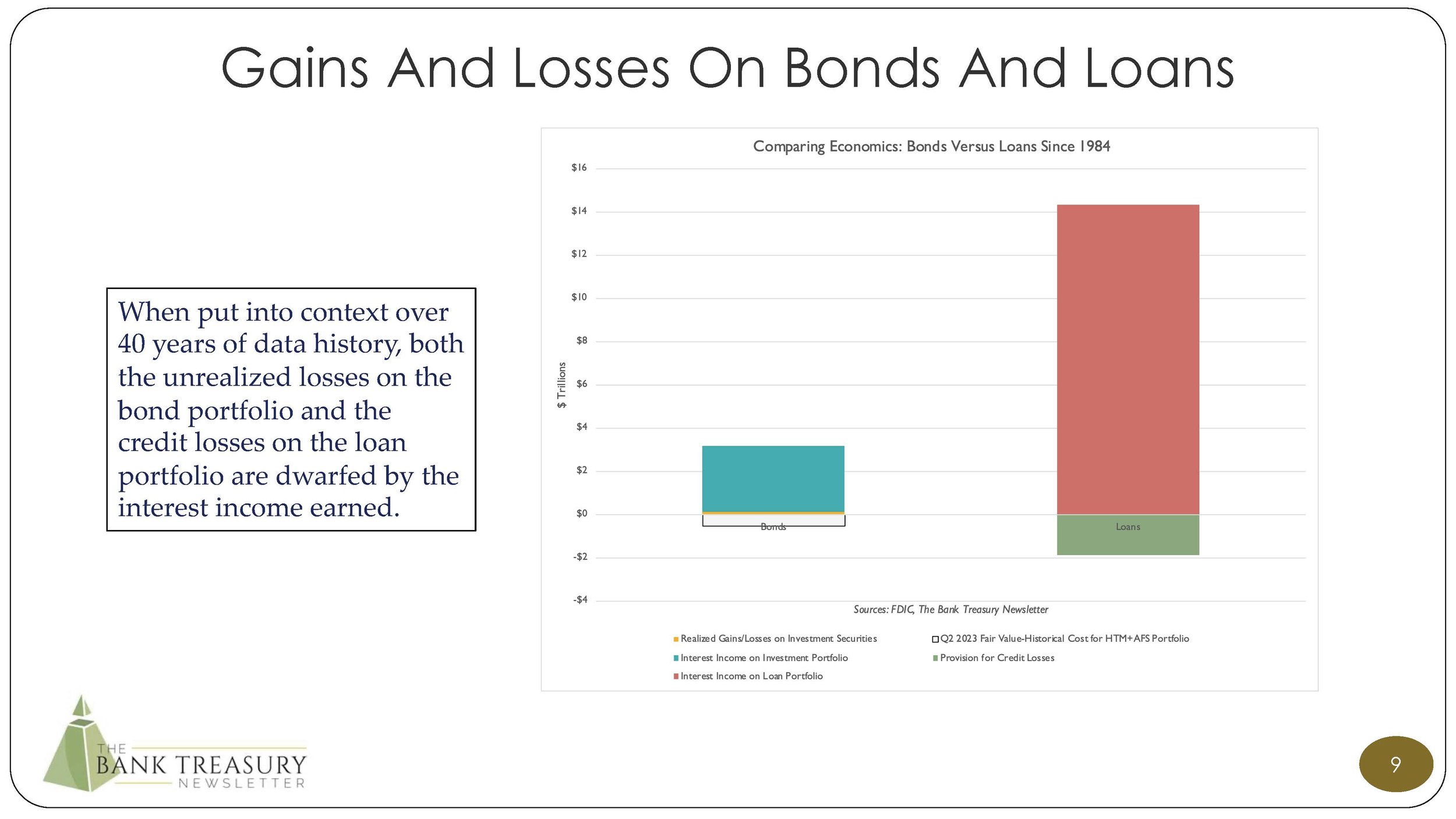

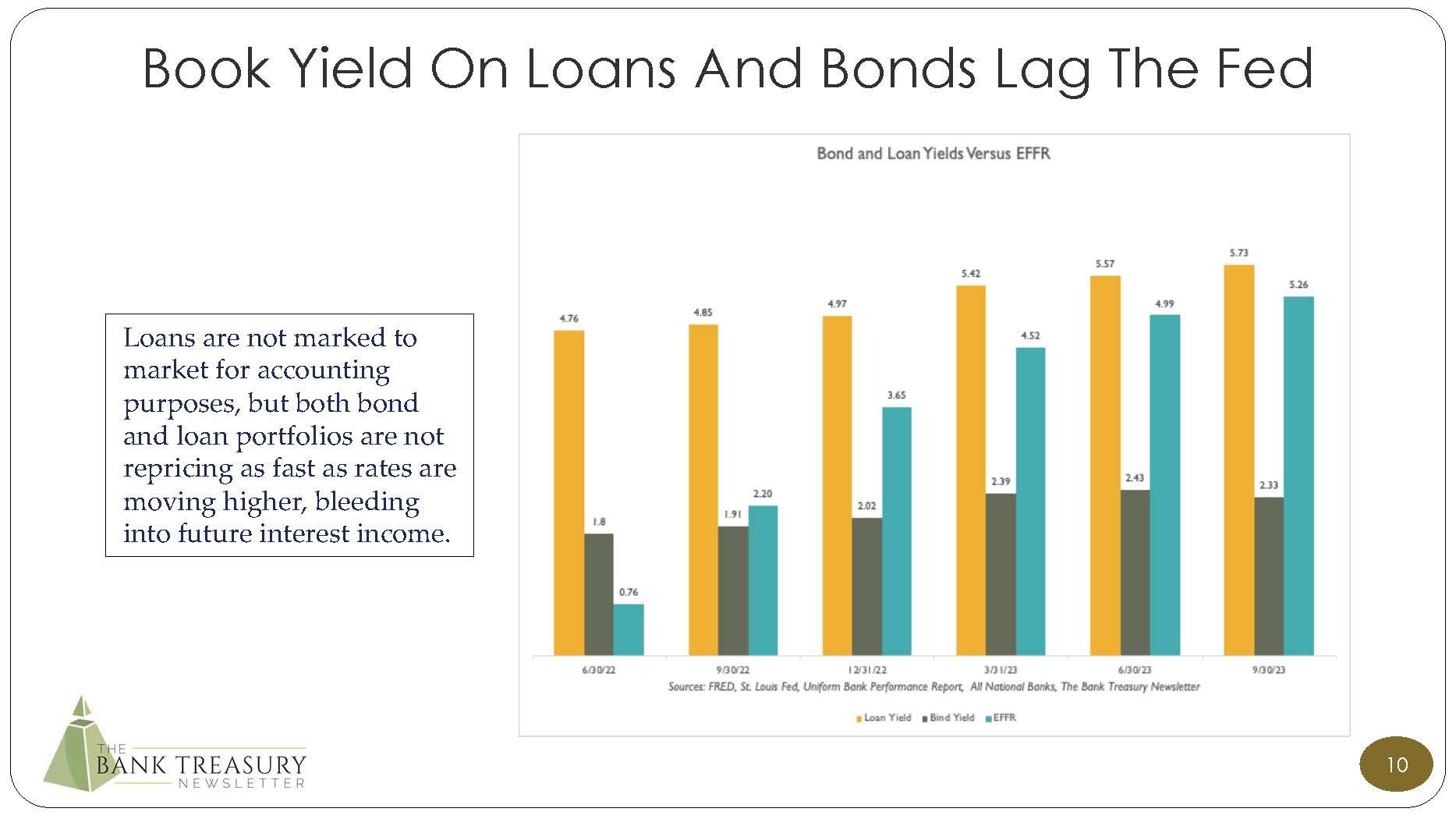

Bank treasurers continue to defer a decision on how and when to rebalance their underwater bond portfolios, uncertain about the direction of rates. On the one hand, as the yield curve bear steepens, the earn back economics to restructure their portfolios are no longer as attractive as they once were in the spring when the yield curve was more inverted, and Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) sold its entire available-for-sale (AFS) portfolio expecting to earn back the loss over three years. On the other hand, since the summer, 30-year mortgage rates are up over 100 basis points, and bond portfolios are even further underwater. See this month’s chart deck for more information on recent trends with the bond portfolio.

The disruption in the U.S. House of Representatives and the possibility of another government shut down could complicate the Federal Housing Finance Administration’s (FHFA) plan to release its findings from the FHLB100 review of the Federal Home Loan Bank (FHLB) system. The report is now expected in November. The review covered the mission and purpose of the FHLBs and occurred during significant bank deposit outflows, a ramp up in lending, and a surge in advance borrowings by banks looking to their FHLBs to plug the gap left from these cash outflows. The review was wrapping up when SVB, Signature Bank (SBNY), and First Republic Corporation (FRC) were failing.

Leaks have fed press speculation that the FHFA may recommend curbs on the largest banks from drawing on advances. The Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC) has long criticized the FHLBs for lending to banks that failed and the FHFA may also recommend more clarity around regulations, such as 12 Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) 1266.4. This rule not only bars FHLBs from extending new advances to members with a negative tangible common equity (TCE) ratio without a written request from their bank supervisor, but also lets FHLBs at their discretion restrict loans to their members facing safety and soundness concerns.

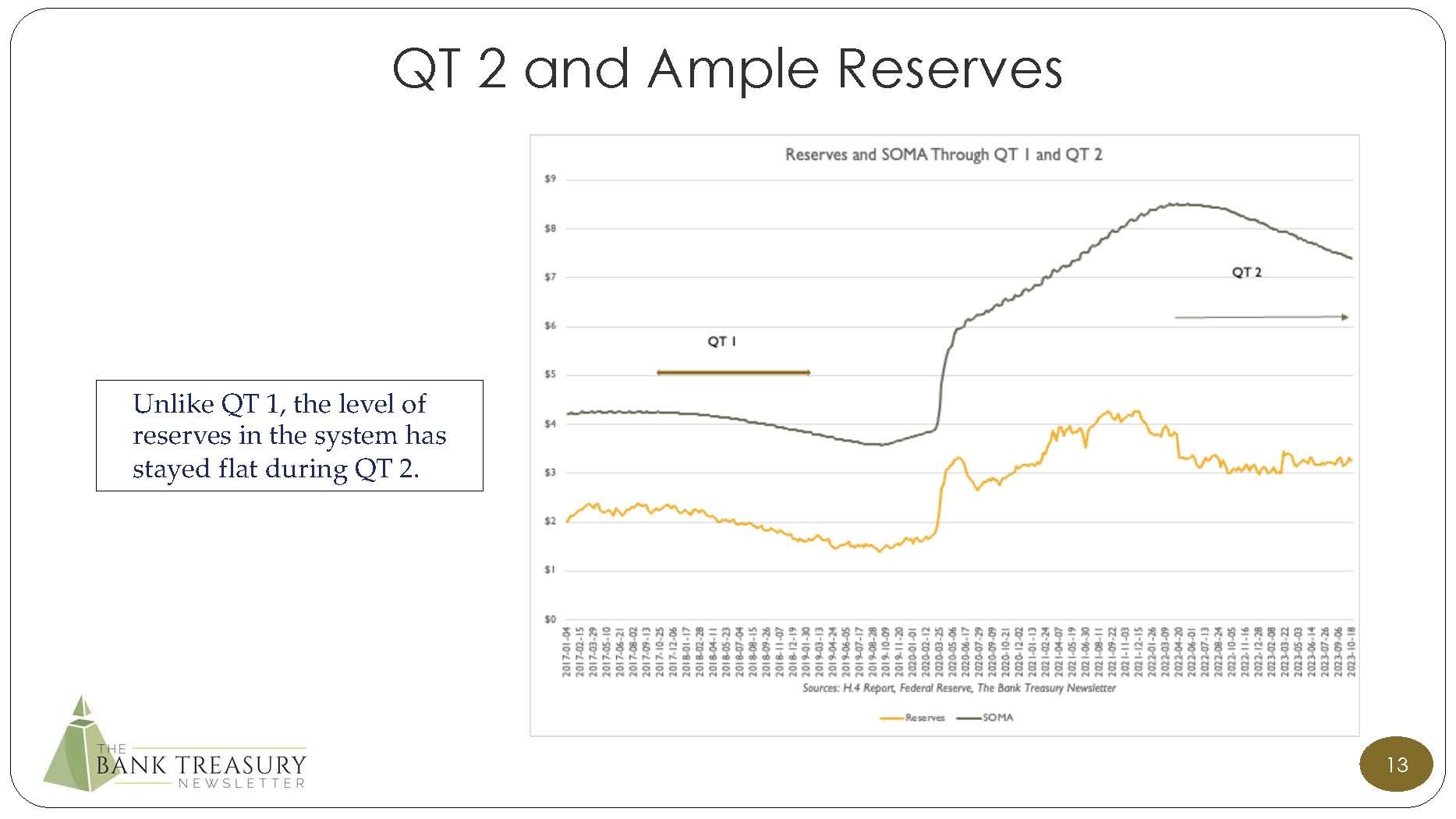

Quantitative Tightening (QT) 2 continues as the $7.4 trillion balance of the Fed’s System Open Market Account (SOMA) is now $1.1 trillion lower than it was in June 2022 when QT 2 began. Fed officials believe there is more room in the Fed’s balance sheet to cut without concern that QT 2 goes too far and triggers a market liquidity crisis. The turmoil caused on September 17, 2019, when the Secured Overnight Financing Rate (SOFR) shot up by over 300 basis points, remains fresh in their minds and a potent reminder for them that they need to tread carefully with QT 2. Fed officials also acknowledge that predicting demand for bank reserves is difficult, and another reason for caution as the Fed tries to balance its goal to reduce its balance sheet while maintaining ample reserves. SOFR replaced the London Interbank Offered Rate (LIBOR) as the main floating rate benchmark, on which a periodically determined credit premium is then added.

Ample reserves are critical to market stability. New tools in its toolkit, including the Standing Repo Facility (SRP) and the Reverse Repo Facility (RRP) may help keep them that way. The SRP, for example, lets it quickly address a sudden surge in demand for reserve deposits. Reducing the balance of its RRP is, from a Fed accounting perspective, the same as increasing its SRP, as both increase bank reserve deposits. Therefore, by reducing the balance of the RRP from $2.2 trillion to $1.2 trillion this month, the Fed effectively neutralized the entire $1.1 trillion run-off from SOMA. During QT 1, the Fed reduced SOMA by $0.6 trillion, to $3.6 trillion, from October 2017 to July 2019, and bank reserve deposits fell by $0.7 trillion, to $1.5 trillion. Since QT 2 began, reserve deposits increased by $0.2 trillion, to $3.3 trillion.

Last April, as it pulled back collateral supply from the repo market through the RRP, the Fed told money market funds that cash raised from short-term investors solely for the purpose to invest in the RRP through sponsored repo would no longer be eligible. Since then, money market funds reduced their investment in the repo market by $0.4 trillion, to $2.9 trillion. Meanwhile, the public’s investment in money market funds continued to grow through last month, to a record $6.0 trillion, but the balance of domestic bank deposits remained unchanged all summer, holding at $16.0 trillion. At their peak in Q1 2022, domestic bank deposits were over $17.0 trillion.

The Bank Treasury Newsletter October 2023

Dear Bank Treasury Subscribers,

Wonk is a weird word and not just because when it is written backwards it spells the word “know.” It turns out that a wonk is a compliment when an American uses the word, and pretty much the complete opposite when it’s used across the pond by a Brit. Thus, the Oxford online dictionary defines the word wonky as referencing something that is askew, and according to Wikipedia, the word might be traced (etymologists are divided) to the old English word “wancol,” meaning someone who is weak or unsteady. Note, by the way, that a wancol has nothing to do with the word “wanker,” a modern British slang with sketchy origins that given our audience is best left undefined.

Here in the land of the free and the home of the brave, the Merriam-Webster online dictionary defines a wonk as someone very passionate about the details, someone who applies their detailed knowledge to high level problems and tries to offer solutions. A wonk loves to cogitate on arcane minutiae and is into trivia and public policy. Remember, not all trivia is trivial.

A wonk forever goes on about history long forgotten. A wonk is a knowledge expert. They read the footnotes, every single word, and look up the citations. A wonk sees the big picture, connects all the dots, even the seemingly unrelated ones, too. Trivia buffs would appreciate that the word only entered the American lexicon about 30 years ago to describe former President Bill Clinton when he was running for office in 1992. Twenty years later he was in fact crowned by American University as its first wonk of the year.

Good to know.

Notably, people who consider themselves wonks bristle at being called nerds. Wonks get invited to Davos. They go to dinner parties with fellow wonks and talk about high level stuff on their minds that is not on the minds of most people. Naturally, they drive an electric car, vacation in Instagram locations, wear cool designer clothes that are environmentally and socially friendly, and may even have a Wikipedia page.

Nerds wear shirt pocket liners for their pens that for some reason they still carry around, ill-fitting clothing, and are awkward in social settings. They drive a used car, and probably are happy eating fast food at their desks with lots of extra polysaturated fats while they get their work done. A lot of what they do goes unnoticed and uncited. Brits may call them something that is best left unsaid.

Bank treasurers are total wonks, even if they have a little nerd in them, too. Yes, many have not been to Davos or Jackson Hole (who has time for vacation these days?), and they may feel awkward and tight around the collar when they meet with their bank’s board and try to project for members when the bank’s underwater bond portfolio will come up for air. Who wouldn’t wish to be anywhere else for that kind of meeting? Try explaining negative convexity to them, the choice between selling bonds now or letting losses bleed through earnings for years to come. Or go into the reason why mark-to- market accounting is just some lopsided accounting nonsense to the no nonsense owner of the local diner or the used car dealer in town. Bank treasury is not easy.

But when our editors sit down with them for dinner, wonky stuff is all they want to talk about. Yes, of course they want to hear what their peers are thinking and doing on their bond portfolio or the latest hedge they are considering. But wonky is not general talk about whether there is going to be an imminent recession or half-thought through speculation what people think the Fed’s next move will be. Everyone talks about the direction of interest rates, or where deposits and loans are headed, but those are headline topics, akin to noting the weather patterns, even if some terms in the bank treasury lexicon, such as “deposit beta” or “contingent funding plan,” sound a little wonky.

For sure, they talk shop, it is all the analyst community cares about. When does your deposit beta peak? What is going to happen to margins? When can you improve efficiency? When will you know more about dividends? How long can the consumer keep spending? How is credit still so good? Explain how Current Expected Credit Loss works again? Hah! So many questions, and still way too much uncertainty. As the CFO of a large global bank told analysts this month,

“I think we're all in a bit of uncharted territory at this point with rates being where they are and the pace at which they got there, quantitative tightening.”

Forecast at your own risk, because it all comes back to the Fed which keeps everyone guessing, as the chairman, president, and CEO of a large regional bank on the east coast said,

“It's a function of how high the Fed goes, and how long does it stay there, and everybody has been wrong so far.”

Everyone likes to talk shop, even wonks, but it is only after you get through that part of the conversation with them that the wonk in them really starts to emerge. When the dinner table is cleared and after-dinner drinks are being served, when it is time to go home but no one wants to leave, yet. When it is time for one more round at the bar. When that steak dinner and that fine Cab are just beginning their digestive journey, that is when the conversation turns wonky.

There are so many wonky issues on their mind, but the first topic is the FHLB. In the last year and especially during the bank failures this past spring, the FHLBs were a key liquidity lifeline for the banking industry. The after-dinner conversation is open-ended, which is good, because FHLBs have a long history. When President Herbert Hoover established them in 1932, they turned out to be one of his lasting achievements, other than the Great Depression, of course.

The mission of the FHLBs was to support the home mortgage market, which was in serious trouble because of the economic situation 90 years ago and the tidal wave of bank failures. As he saw it, the FHLBs would provide needed liquidity for the market enabling lenders to provide credit by supplementing their shrinking deposit balances. As bank treasurers remember, in 1932 people were withdrawing their life’s savings from banks to save under their mattress because there was no FDIC. That had to wait for President Franklin Roosevelt, who did not sign the FDIC Act into law until 1934.

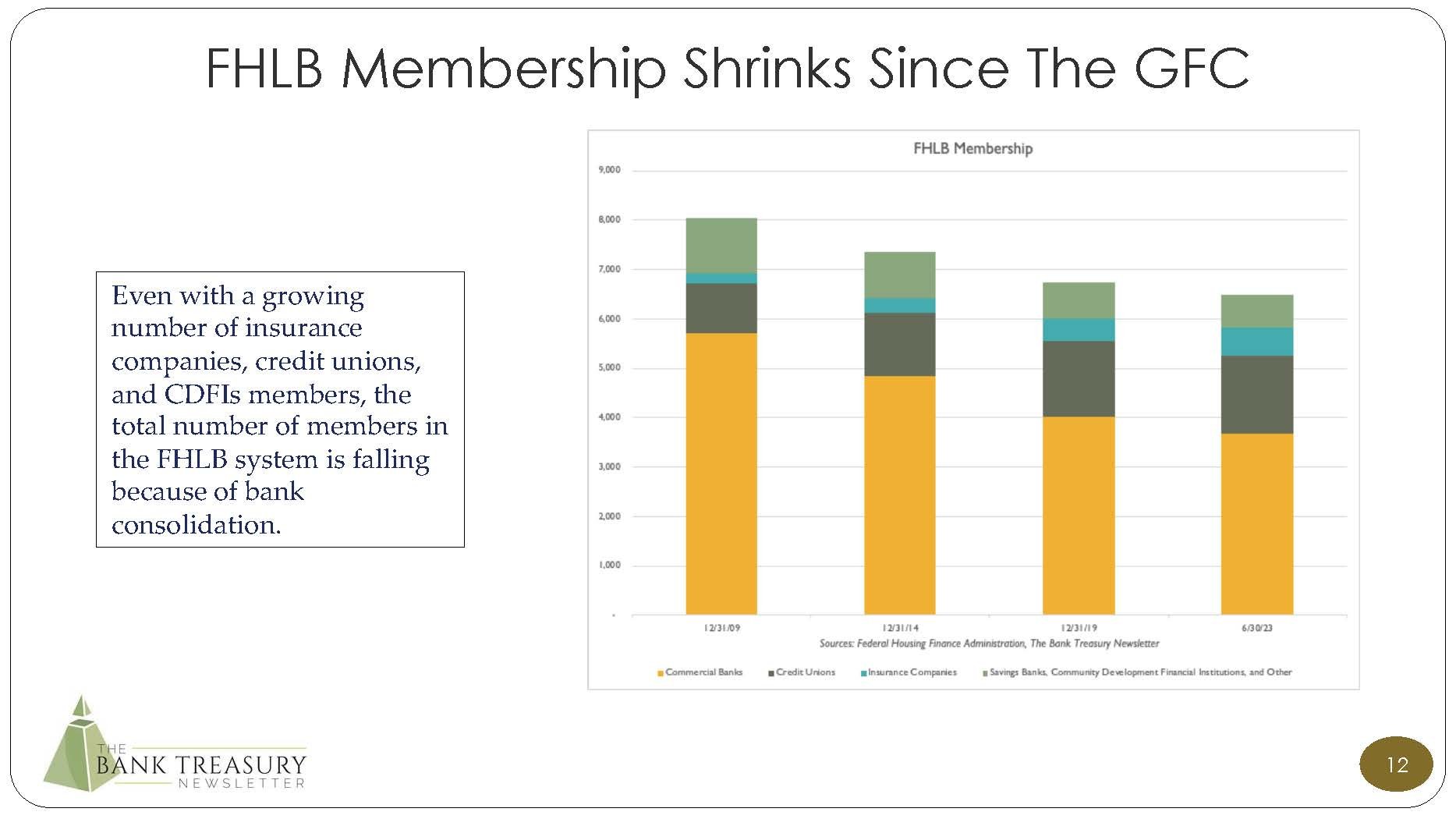

But for commercial banks, FHLB history all began with the 1989 Financial Institutions Reform, Recovery, and Enforcement Act (FIRREA) which opened the door for the first time to let them, also credit unions, become members of the FHLB and gain access to advances. Before FIRREA, only chartered thrifts and savings and loans (S&Ls) were eligible for membership with the FHLBS. Today, there are no more chartered thrifts or S&Ls, though there are savings banks and savings associations. As of Q2 2023, FHLB membership consisted of 3,679 commercial banks, 1,591 credit unions, 72 community development financial institutions (CDFIs), 570 insurance companies, and 581 chartered savings associations and savings banks. (See this month’s chart deck detailing how commercial bank membership in the FHLBs has been shrinking since the Great Recession, their ranks thinned through bank consolidation.)

In 1989, the S&L industry was still reeling from the crisis in the early 1980s. In decline, its numbers were shrinking from failures and consolidation, and so was membership in the FHLB system. The FHLBs needed new members to stay relevant to the home mortgage market which was shifting over to commercial banks. FIRREA thus became a critical lifeline for the future of the FHLBs and the mortgage market. Not only today are commercial banks the FHLBs’ largest membership group, but they also accounted for 55% of the FHLB’s advances at the end of Q2 2023.

The FHLBs, regulated and supervised by the Federal Housing Finance Administration (FHFA) under the Dodd-Frank Act, are cooperatively owned by its members and funded as a government-sponsored enterprise (GSE) through the FHLB-Office of Finance. The FHLB Act that President Hoover signed was intended to help community banks which did not have and still do not have the same access as their large bank peers to the debt capital markets for alternative funding.

But the largest banks today account for more than a quarter of all advances in the system and half of all advances to commercial banks. It is hard to know what Herbert Hoover would have thought about these developments, but the notion of a GSE primarily helping the largest institutions in the U.S. does not sit well with the public policy wonks working today at the FHFA or the FDIC, or with their supporters in Congress on both sides of the political aisle.

Now it is true that the mortgage market is a lot different today than it was in Herbert Hoover’s time, so it is only appropriate that FHLB membership should evolve with the times. Obviously, there were no CDFIs back then, much less the technology for asset securitization. Fannie Mae, Ginnie Mae, and Freddie Mac were not even in the picture. Today, according to the flow of funds report for Q2 2023, residential mortgage loans outstanding equaled $14.0 trillion. Commercial banks accounted for $2.8 trillion of these loans outstanding, compared to the GSEs, which owned $7.5 trillion of them. Most of the rest is securitized and owned by the entire universe of fixed income investors, including domestic and foreign commercial banks, insurance companies, real estate investment trusts (REITs), and other investors here and abroad.

According to the Fed’s H.8 data, the small bank peer group owned $1.5 trillion of the residential mortgage loans and Agency-guaranteed MBS outstanding, compared to $3.5 trillion held by the large bank peer group. Thus, public policy considerations aside, large banks are a critical part of the home mortgage market. Perhaps the public policy debate today should not be about curbing FHLB membership for large banks, but how can membership be expanded. But finding ways to increase advances to banks is not likely on the menu for policymakers at the FHFA. The FHFA is instead considering expanding access to advances for nonbank mortgage lenders.

In any case, the reason why, with drinks in hand, FHLBs come up as topic number one this month, is because of the FHLB100. Because as everyone in the bank treasury world knows, because their FHLB coverage keeps reminding them over and over, the FHLB100 is a very big deal. Honestly, it does not get the headlines it deserves. Membership eligibility is just a part of the story.

The FHLB100 was a wide-ranging six-month review of the FHLBs led by the FHFA, which concluded last March. Everything was on the table. Policymakers at the FHFA believe that after 91 years, the FHLB system could use an upgrade. And, yes, there is speculation that one of the recommendations to Congress to “improve” the system could include a curb on the eligibility of large banks to borrow from their FHLBs. But treasurers at smaller banks care about the FHLB100, too. Sandra Thompson, the FHFA’s director, in her Congressional testimony last May, said the review covered,

“…the mission and purpose of the System, the efficiency of its organization and operations, and its effectiveness in supporting affordable, sustainable, and equitable housing. In addition, we examined the System’s role in community and economic development, including addressing the unique needs of rural and financially vulnerable communities. Finally, we looked at the System’s member products, services, and collateral requirements, as well as its membership eligibility requirements.”

Obviously, the timing of the review could not have been better, as the FHFA could see in real time just how critical the FHLBs are to the financial system. While officials from the FHFA were conducting their listening sessions with member and non-member stakeholders, the Fed was busy raising interest rates effectively to infinity and shrinking its balance sheet by over $1 trillion. Deposits were leaving banks, loans were growing, and banks were leaning on the FHLBs for funding in a major way. As the review was concluding last March, SVB and SBNY were failing. Advances the FHLB had extended to Silvergate Bank were in the news.

As the financial system shuddered under the stress, the Fed was forced to create a new lending facility, the Bank Term Funding Program (BTFP), and as they began to review their findings last May, FRC failed which, together with SVB and SBNY, cost the FDIC’s Deposit Insurance Fund over $30 billion. And in the wake of the bank failures, deposits flowed out of banks to money funds in a wave, and banks drew down even more heavily on their advance lines to shore up their liquidity.

There was a lot of listening on the part of the FHFA staff who conducted the review. FHLB members could not have been more effusive in their praise for the FHLBs helping them through the enormous balance sheet stresses they faced last spring. As she went on to say,

“Through this period of market stress, the FHLBanks remained in a safe and sound condition and continued to serve their critical role. The System’s resiliency in the face of significant market volatility showed the effectiveness of the standards FHFA established for the FHLBanks to ensure they are appropriately prepared for stress events.”

But there is a but. In fact, there are several.

But, as any wonk would tell you, it is very nice to say that large banks should not take advantage of FHLB advances, funds that are really intended for the community banks. But if large banks are going to be curbed from borrowing from the FHLBs, who will support the market for FHLB bonds? Why would large banks participate in the FHLB’s primary overnight bidding group, if they are not going to be eligible as members? With $1.2 trillion in FHLB bonds outstanding, a record sum that went to fund the advances policymakers still want the FHLBs to make to community banks, this seems like an awkward time to be bringing up membership eligibility.

You think?!

But even if the FHLBs were awesome in their membership’s hour of need, this does not mean that making advances to all institutions based solely on the value of collateral is good public policy. Some wonks might call this, and have called this for years, the essence of moral hazard, which is a very wonky topic in and of itself. After all, if the FHLBs have a super-lien on a failing bank’s balance sheet, its claim is ultimately dependent on the FDIC becoming the receiver of the bank’s assets and honoring the FHLB’s super-lien.

But talk about conflicts of interest. Should one public agency (the FHLBs) get made whole at the expense of another (the FDIC) and call that a win-win? Put another way, is it a good idea for FHLBs to lend to banks that face the risk of failing, if the ultimate party that pays is the taxpayer? There was even an FDIC study from July 2005 that found a causal link between a bank’s drawdown on advances and higher losses sustained by the FDIC. Basically, advances can kill a bank, the FDIC, and taxpayers. As Sheila Bair, the former chair of the FDIC told Bloomberg Magazine in 2008, the FDIC has,

"…a beef with excessive reliance on Federal Home Loan Bank advances.”

But! But you are damned if you do and damned if you do not. But is it good public policy for the FHLB to deny credit to one of its members, knowing that by denying credit, it may cause that member to fail? As a spokesperson for one of the FHLBs said in 2008, explaining why it had lent money to IndyMac which failed during the Global Financial Crisis (GFC),

"It is not our role to cause a liquidity problem for a member institution,"

But that is not completely accurate. The FHLBs do not lend recklessly even if their credit extensions are based on the value of a member’s eligible collateral. For example, as bank treasurers remember because this topic first popped up a year ago, there is a rule in the CFR, 12 CFR Section 1266.4 to be exact, which explicitly prohibits FHLBs from extending new advances to members with negative TCE unless they receive a written request from the member’s supervisor to make that loan.

12 CFR etcetera was starting to worry bank treasurers who suddenly found themselves (if not technically, then in spirit) with other than temporarily impaired book equity from a generally accepted accounting principle (GAAP) perspective. Yes, the bank’s supervisor can write a request to the FHLB to make the advance in a pinch, but have you ever heard of two or more different government agencies, such as the Fed, the FDIC, and the FHFA, in functional cooperation? After all, the reason why the FHFA still included a GAAP capital rule that included Accumulated Other Comprehensive Income (AOCI) going back to 1994 instead of the revised regulatory capital rule that was adopted later in 1994 and which excluded it is a study in government dysfunction. Inter-agency dysfunctionality is one of the issues brought up by the Fed as leading to the SVB fiasco, as it discussed in its report on SVB published at the end of April.

So, a FHLB has no choice but to say no if a member has negative TCE. And even at its discretion, if in its judgment the member is at risk of failing, 12 CFR 1266.4 tells them they can say no. Simple. Just say no, go to the Fed window if you need a loan. But the problem is that it is not simple. FHLBs have extended advances to banks that failed, and this has cost the FDIC a lot of money, from IndyMac, Wamu, and Countrywide, to SVB, SBNY, and FRC. The drum beat against the status quo has grown too loud to ignore, even if the only people who can hear it are fellow wonks.

But saying no to a member is not so easy. After all, the FHLBs have competition, so even if the FHLB refuses a member’s advance request, that member could turn around and raise funding in the retail brokered CD market, which since the GFC eclipsed advance borrowings as a primary non-core deposit funding source. At the end of Q2 2023, bank treasurers used brokered CDs to fund $1.2 trillion of their bank balance sheets, while advances funded $0.7 trillion. Forcing banks out of advances because policy wonks believe that advances are bad and will cost the taxpayer, may end up costing the taxpayer even more money when bank treasurers cycle out of advances into retail, fully-insured, brokered CDs. Deposit behavior is already leading a shift from uninsured to insured deposits across the size spectrum of commercial banks (Figure 1).

In any case, the FHFA’s report, summarizing the findings from its review with recommendations for Congress how to reform the FHLBs, will be out soon, as Director Thompson promised Congress last May.

“The FHFA is now in the process of analyzing these and other suggestions and preparing our report for publication later this year.”

Which is wonderful, but for the fact that time is running out, and there is the little matter of the impending government shutdown next month. If the government shuts down, the report may need to wait until the lights and computers can be turned back on at FHFA offices. And even if they do get the report out before year-end, given Congress is dysfunctional, has no Speaker, could barely get the debt ceiling raised, and is counting down to the next shutdown, who really believes that it will have any bandwidth to even begin to consider what the wonks at the FHFA have to say.

Forget about it!

Then again, if the FHLBs do not try to reform their ways, the FDIC, where Director Thompson worked before joining the FHFA, may do it for them through its assessment calculator. The FDIC has from time to time considered amending its assessment calculator to include a surcharge for reliance on non-core deposit liabilities, and liquidity risk is already included in the analysis for large banks over $10 billion. An explicit charge for advances would be a big deal, as it has never been included in the algorithm. Charging extra when a bank relies on advances and uninsured deposits for its funding needs was discussed in the FDIC’s review of options to reform deposit insurance published last May, but Congressional review may limit many of the reforms it proposed.

Figure 1: Uninsured Deposits ($250,000+) as % Insured and Uninsured Deposits

Discouraging banks from borrowing from the FHLB may not be good public policy. In a survey the FDIC conducted back in 2004, the primary reason why community banks rely on advances is to fund loans (34%), buy bonds (22%), and manage interest rate risk (20%). Liquidity needs (12%) is a distant fourth reason for them to borrow from the FHLB. Those are probably still the main reasons in descending priority why banks borrow from the FHLB, and usually not because their depositors are rushing out the door and they are rushing for a lender of last resort. There is nothing routine about going to the Fed.

Which is understood, but from the FDIC’s perspective, routine or not, if banks need liquidity, they really should go to the Fed’s discount window, or now (at least until next March unless it gets extended) they can go to the Fed’s BTFP. Yes, there are signaling risks when a bank borrows from the discount window or the BTFP, but if a bank is in danger of failing without a liquidity lifeline, that is what the Fed’s lender of last resort role is all about. How does a bank treasurer at an institution with liquidity issues make a case that the bank is still a “going concern” and that the public should not be signaled when they need money in a hurry?

But there is a big difference between the FHLBs lending advances to banks, and the Fed lending through its discount window aside from signaling issues. When the Fed lends through the discount window or the BTFP, it increases total assets on the left side and reserve deposits on the right side of its balance sheet. In essence, discount window lending is quantitative easing.

On March 2nd, for example, immediately prior to the bank failures, the Fed reported that its SOMA portfolio equaled $7.9 trillion. This month, as of the 10th, it reported that SOMA was down to $7.4 trillion. However, that $0.5 trillion reduction was partially offset by the BTFP, which equaled $109 billion, and a credit extension to the FDIC to cover the SVB, SBNY, and FRC failures ($57 billion).

The hour grows late, the waitstaff want to close and go home, but bank treasurers want another round. They want to talk about SOFR. SOFR is not unrelated to what happens to the FHLBs, if for no other reason than the FHLBs are the dominant cash supplier in the Fed fund market. Apparently, even in an ample reserve environment, there are still commercial banks that occasionally find themselves short and need to buy reserves, which the FHLBs are only too happy to sell.

This is because the FHLBs are not eligible to deposit their reserves at the Fed, and since the effective Fed funds rate pays better than the Fed’s RRP, the Fed funds market is a good deal when they have some extra cash lying around that they do not need for funding member advances. Of course, if there is some reason why they will not need to make those advances in the future, say some curb on advances to the largest banks that account for the majority of the advances, or some regulatory ban on providing cash to members when deposits are shrinking and loans are growing, maybe they will have more money to put to work in the Fed funds market. They may even have some extra money to put into the Fed’s RRP where, unlike the Fed’s reserve account, their money is welcome.

Everything is connected. Repo is a major part of the money market. The FHLBs are a major provider of cash to the Fed funds market, which is also part of the money markets. The money market funds are the dominant provider of cash in the repo market, and the Fed is a key provider of collateral and price setter through its RRP in the repo market.

The RRP is also a key determining factor for SOFR. Since July 1st, most of the floating rate loans that bank treasurers have made that would have been priced off the now-defunct LIBOR are being priced on SOFR terms. Today, SOFR is the dominant benchmark in the floating rate world, used for commercial and consumer loans, advances, swaps, and other floating rate financial instruments. So, what happens to SOFR matters. The transition from LIBOR to SOFR got a lot of press during the transition period leading up to key dates, but today the financial system has moved on and is taking SOFR in stride.

At one time during the transition, SOFR had competition from credit-sensitive indices, including Ameribor and Bloomberg Short-term Bank Yield Index (BSBY). They were promoted as better than SOFR because they included a credit component that LIBOR had but SOFR lacked. But today they are nothing more than footnotes to the SOFR story. Interesting factoid: SBNY was one of the first and only issuers of floating rate debt outstanding benchmarked to Ameribor. Today, there are no new floating rate bonds benchmarked to either Ameribor or BSBY. SOFR is pretty much it, which is just as the Fed wanted.

And SOFR has been boring, tied tightly around the rate the Fed pays on the RRP and solidly in the Fed’s target Fed funds range. But bank treasurers well remember that this has not always been the case. In fact, up until a year ago, the Fed had a lot of trouble keeping SOFR in its target range for the Fed funds rate, as around quarter-ends it would spike above or below the range. On September 17, 2019, SOFR suddenly spiked up by 300 basis points to 5.25%, caused by a sudden shortfall in reserves, which was tied to a spike in reserve demand, which was connected to deposit and money market fund outflows to cover tax payments.

In the aftermath of that turmoil, the Fed more than doubled the level of bank reserves in the system and today, more than a year after it began QT, it remains committed to maintaining ample reserves. Ample reserves means that the aggregate supply of reserves well exceeds aggregate demand. As a result of this policy, the Fed can only control the effective Fed funds rate by raising the Interest rate On Reserve Balances (IORB) (currently set at 5.40%) and its rate on its RRP (currently set at 5.30%). But the benefit of ample reserves and the RRP is that SOFR volatility is a thing of the past. SOFR has been anchored a basis point or two above the RRP. With the RRP at 5.30%, SOFR averaged 5.31% over the past 30 days.

Now the Fed will admit that it is not certain about the ideal level of bank reserve deposits, when ample is just abundant, or not enough. Reserves might be ample now, but they may not be tomorrow. Or the next minute. Roberto Perli, the manager of the Fed’s SOMA portfolio, told the National Association for Business Economics this month that forecasting reserve demand is very difficult,

“Demand for reserves is not static. Indeed, it can be highly variable and difficult to observe in real time, and even more difficult to forecast. Second, demand for reserves is not only time-varying but also non-linear. That means that under some circumstances, small changes in the quantity of reserves can generate a large change in federal funds rates relative to administered rates.”

The Fed still thinks it has things under control. And even if there were another event in the repo market as what happened on September 17, 2019, it believes that the SRP it established could be used in an emergency to pump liquidity back into the system. With the SRP and its other monetary policy tools at its disposal, the Fed has more room to shrink its balance sheet without worrying this could trigger another mishap in the repo market. Perli continued,

“First and foremost, all indications are that reserves today remain abundant. We see no clear evidence of stress in either the pricing of overnight interest rates or the usage of backstop facilities. Second, our operating framework has proven its capacity of redistributing liquidity as needed and at a relatively low cost. This is clear from the ability of private markets to draw funds out of the ON RRP at just a modest premium over the offering rate for that facility. Third, we can maintain rate control and the smooth functioning of money markets under a wide range of conditions and through material stress…to alleviate acute demand for precautionary liquidity in response to broader stress in the banking system. This is all encouraging, but we remain cognizant of the risks and uncertainties ahead.”

Acknowledging these uncertainties, with no evidence that tools such as the SRP will work in a stress scenario, with no track record of success to point to other than the fact that nothing has gone wrong yet, he was confident that the Fed will know the right time to end QT when it sees it,

“The FOMC intends to slow and then stop runoff when reserve balances will be somewhat above levels consistent with ample reserves. The Committee will make that judgment based on careful analysis and market monitoring that incorporates price signals from money markets as well as extensive market outreach and intelligence. Experience has also given us confidence in the efficacy of our tools should short-term stress arise. The combination of a resilient and flexible operating framework and the constant vigilance of the extraordinarily talented and dedicated professionals on the Desk gives me confidence that balance sheet normalization can be accomplished without significant disruptions to short-term funding markets.”

But QT 2 is nothing like QT 1. During QT 1, the Fed reduced SOMA and reserve deposits by $0.7 trillion, stopping QT when SOMA fell to $3.5 trillion, and reserves fell to $1.5 trillion. During QT 2, the Fed reduced SOMA by $1.1 trillion, to $7.4 trillion, but increased reserves by $0.2 trillion, to $3.3 trillion. It was able to hold reserves but shrink SOMA thanks to the RRP, which fell by $1.0 trillion from its peak, to $1.2 trillion. To date, pulling collateral out of the repo market, shrinking SOMA, and raising the Fed Funds target range has not had any effect on SOFR, but as the Fed admits, there is a lot of uncertainty when it comes to reserve demand and money market flows.

The money markets are only part of the worry with SOFR. Because the SOFR benchmark lacks a credit component, lenders tack a credit premium on top. There was a lot of concern during the transition how the credit add-on would work when credit deteriorates. As the add-on was set periodically and not continuously, lenders could pull back from credit markets in times of extreme uncertainty and exacerbate credit stress. However, since 2020, despite a global pandemic, bank failures, not to mention QT and the rate hikes, credit risk has stayed remarkably stable. Presumably then, the credit premium add-on has not changed much, and not presented any great operational difficulty for lenders. In Figure 1, the spread between BBB Corporates and 5-year Treasuries during the SOFR transition and QT 2 has been relatively flat.

Figure 2: BBB Corporate Spread to 5-Year Treasury

Of course, circumstances change like the suddenly chilly weather outside. The chairman and CEO of a global banks warned analysts this month that he knew something was coming. He may not know how bad and when, but nothing good lasts forever.

“Because markets do well is not a reason ever to say they're going to continue to do well. If you don't believe me, remember 1987, 1990, 1994, the year 2000, the year 2009. And people don't predict those inflection points. I just -- but my caution is that we are facing so many uncertainties out there. You just got to be very cautious…We know there are going to be bad times. That's not a surprise that there could be bad times. We don't always know how they're coming and where they're coming from.”

Lights are being shut, coats are pulled on against the fall chill outside, and goodbyes are being said. Until next time, but before everyone leaves, one more big picture topic. There is a slight groan among the waitstaff, but let’s continue a little further.

The Basel 3 endgame proposal directly impacts a couple dozen banks with assets over $100 billion, and the proposed capital requirements for operational risk and market risk will only hit the largest institutions, those banks that are the primary dealers in the repo markets, the fixed income markets, the banks providing the market liquidity for FHLB debt, Treasurys, MBS, Corporate bonds, and other fixed income securities. The proposed capital requirements, the comment period of which regulators just extended, will be expected to reduce the returns in some trading businesses, which in turn could lead to market consolidation.

So, here is the question. If there are less liquidity providers in the markets, will this lead to more market volatility, and is this the new normal? The above-quoted chairman and CEO could not agree more. Regulations will come at the cost of liquidity.

“Market making is a critical function. and if you look at the world, there are only so many large market-makers who can make markets for governments, hospitals, cities, schools, states, IMF, World Bank, BlackRock, Blackstone…Market-makers have a different function than hedge funds. And I don't know what the real intent was, but this is another one, I think, needs to be really thought through. What are you trying to accomplish…It could force people out. It will force lower positions…. and obviously more volatile markets because with all the constraints for the Liquidity Coverage Ratio, Supplementary Leverage Ratio, et cetera, you will constantly be up against limitations on what you can do.”

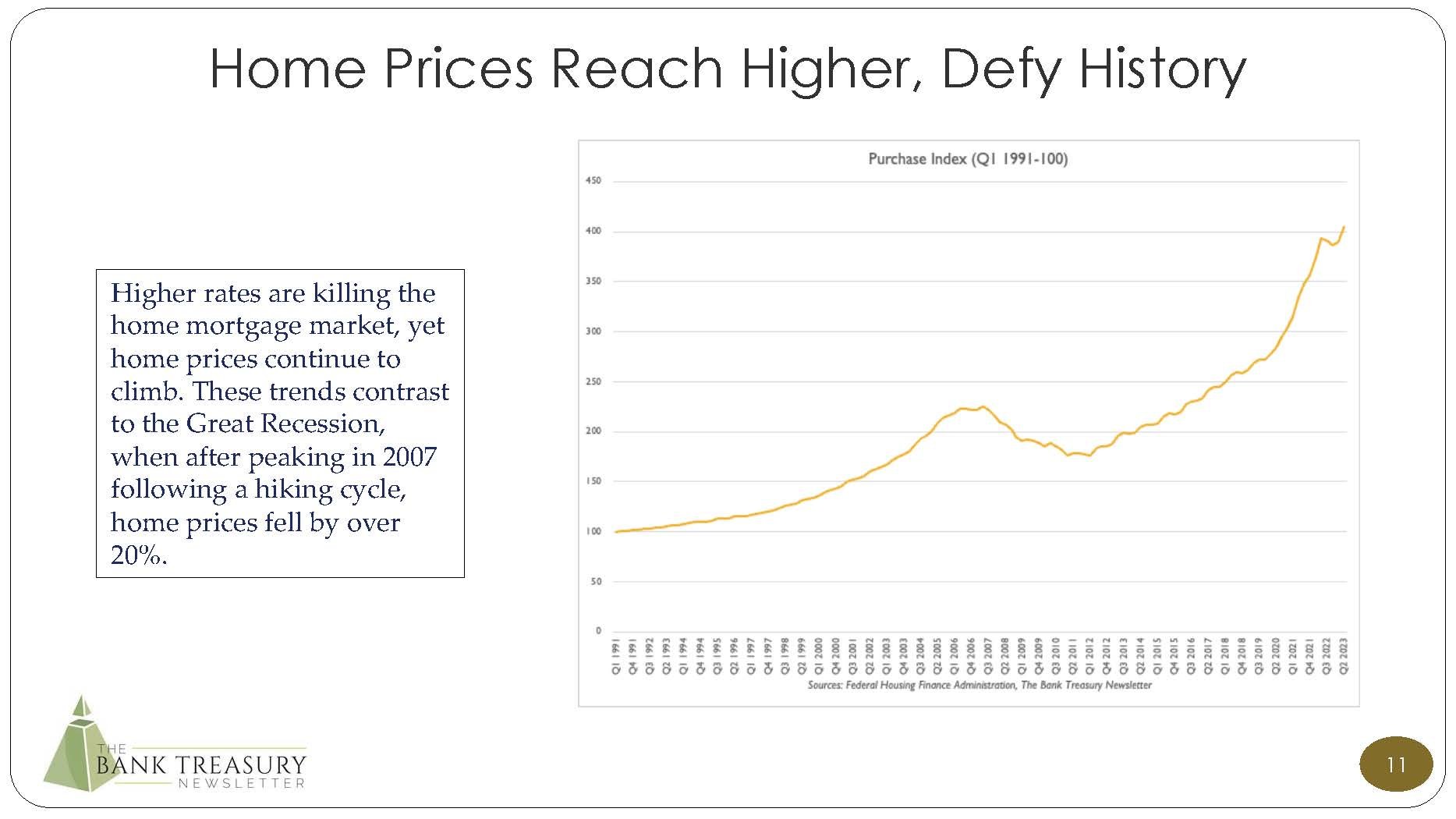

There is a lot of risk in the world these days and the stress in the bank treasury world remains considerable. Uncertainty reigns. Despite enormous pressure, bank treasurers tell the newsletter they are not panicked and continue to hold off on any major change in their bond portfolios. They are thinking about hedges, but the timing is still off. Meanwhile, the yield curve continues to bear steepen, the front end staying anchored, and the back end is rising, the 10-year poking over 5%. And mortgage rates are up, meaning that any bonds they bought last summer are already underwater like the rest of the portfolio. But they are not perturbed.

FOMC participants’ policy path chart (“dot plot”), September 2023

This is the time to watch and observe the markets, they say. Bank treasurers, like all wonks, like to sit back, pay attention, and connect the dots, and the dots are telling them to watch and wait on that bond portfolio restructuring. That said, the dots are also telling them that the wait may be ending. Then again, as they have learned, tomorrow everything can change.

The Bank Treasury Newsletter is an independent publication that welcomes comments, suggestions, and constructive criticisms from our readers in lieu of payment. Please refer this letter to members of your staff or your peers who would benefit from receiving it, and if you haven’t yet, subscribe here.

Copyright 2023, The Bank Treasury Newsletter, All Rights Reserved.

Ethan M. Heisler, CFA

Editor-in-Chief