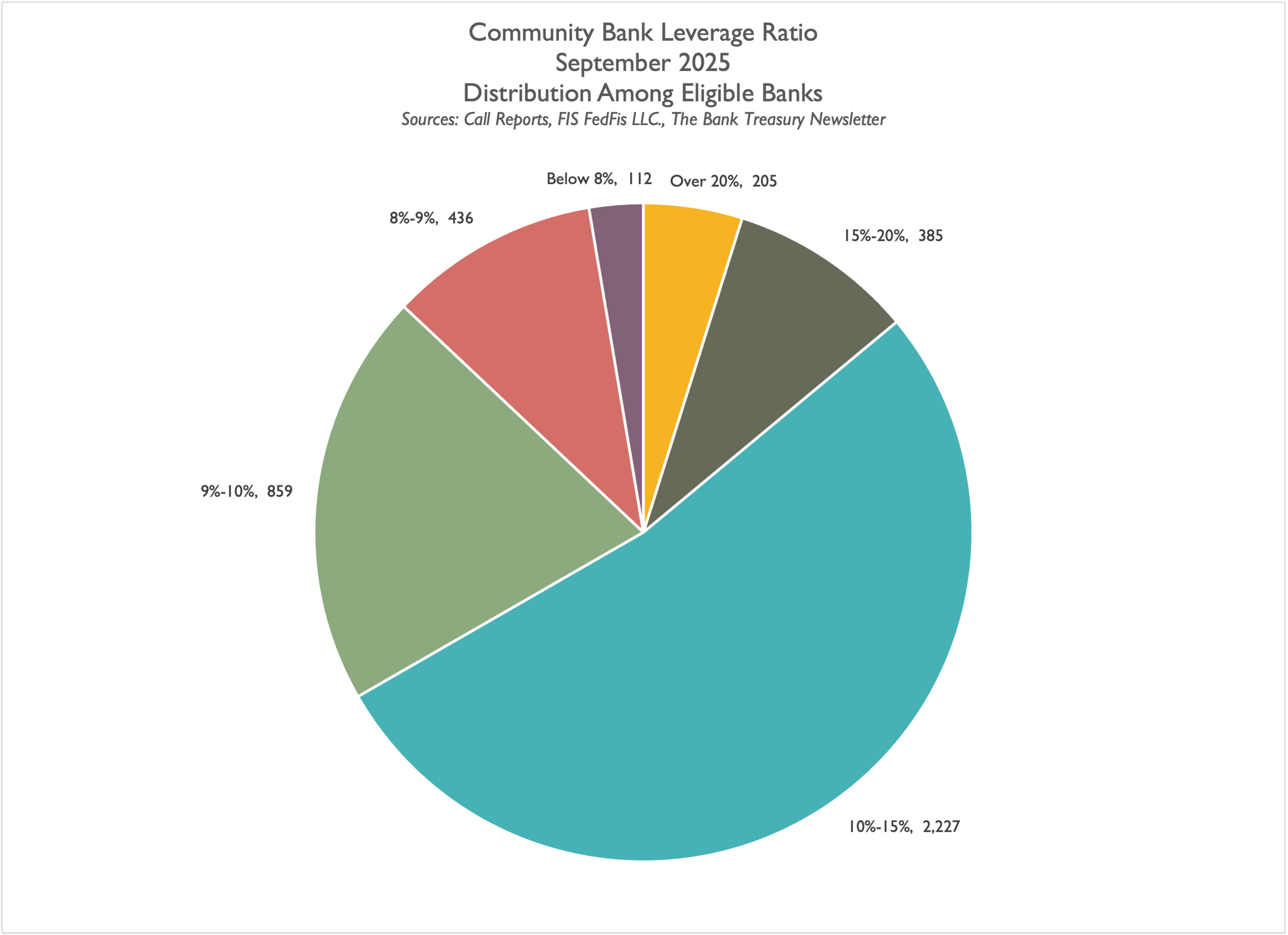

As initially proposed by regulators, the minimum threshold for the Community Bank Leverage Ratio (CBLR), which equates to the Tier 1 leverage ratio, was 10%. Commercial banks with less than $10 billion can opt to report the Tier 1 and total risk-based capital ratios. When they finalized it in 2019, however, they lowered the minimum to 9%, and late last year, they proposed reducing it further to 8%. As of September 2025, the CBLR for 10% of all CBLR-eligible institutions ranged from 8% to 9% (Slide 1).

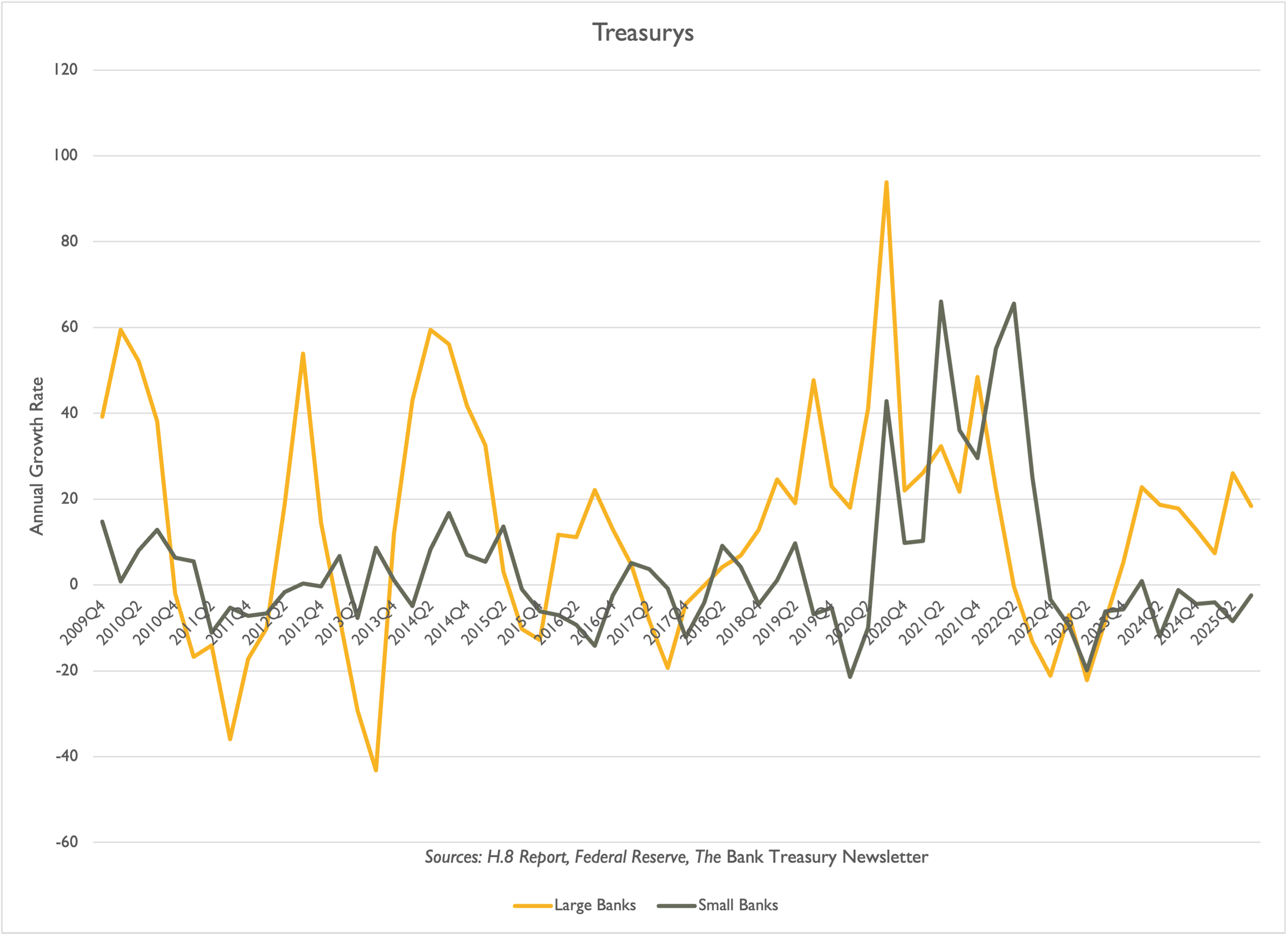

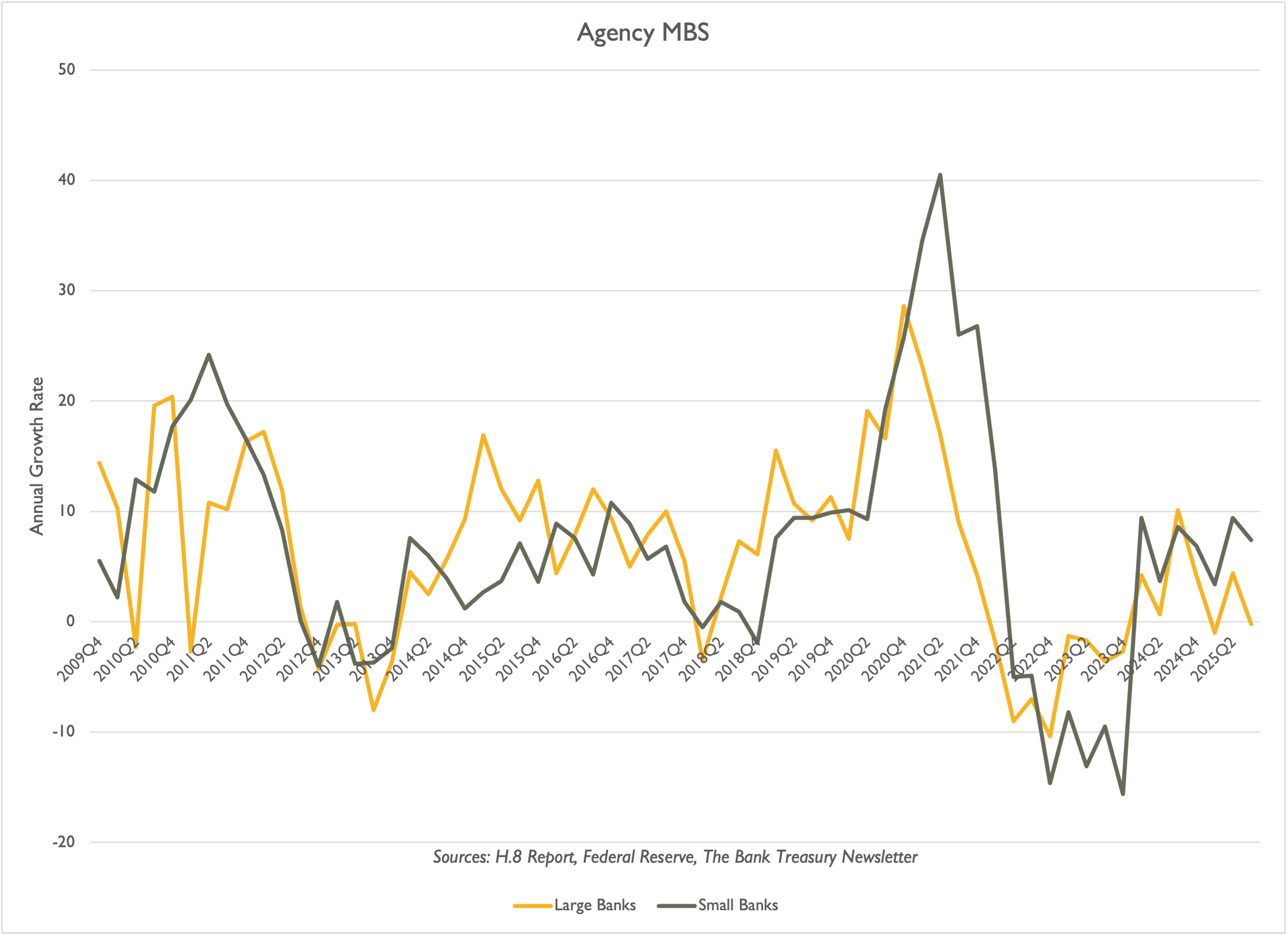

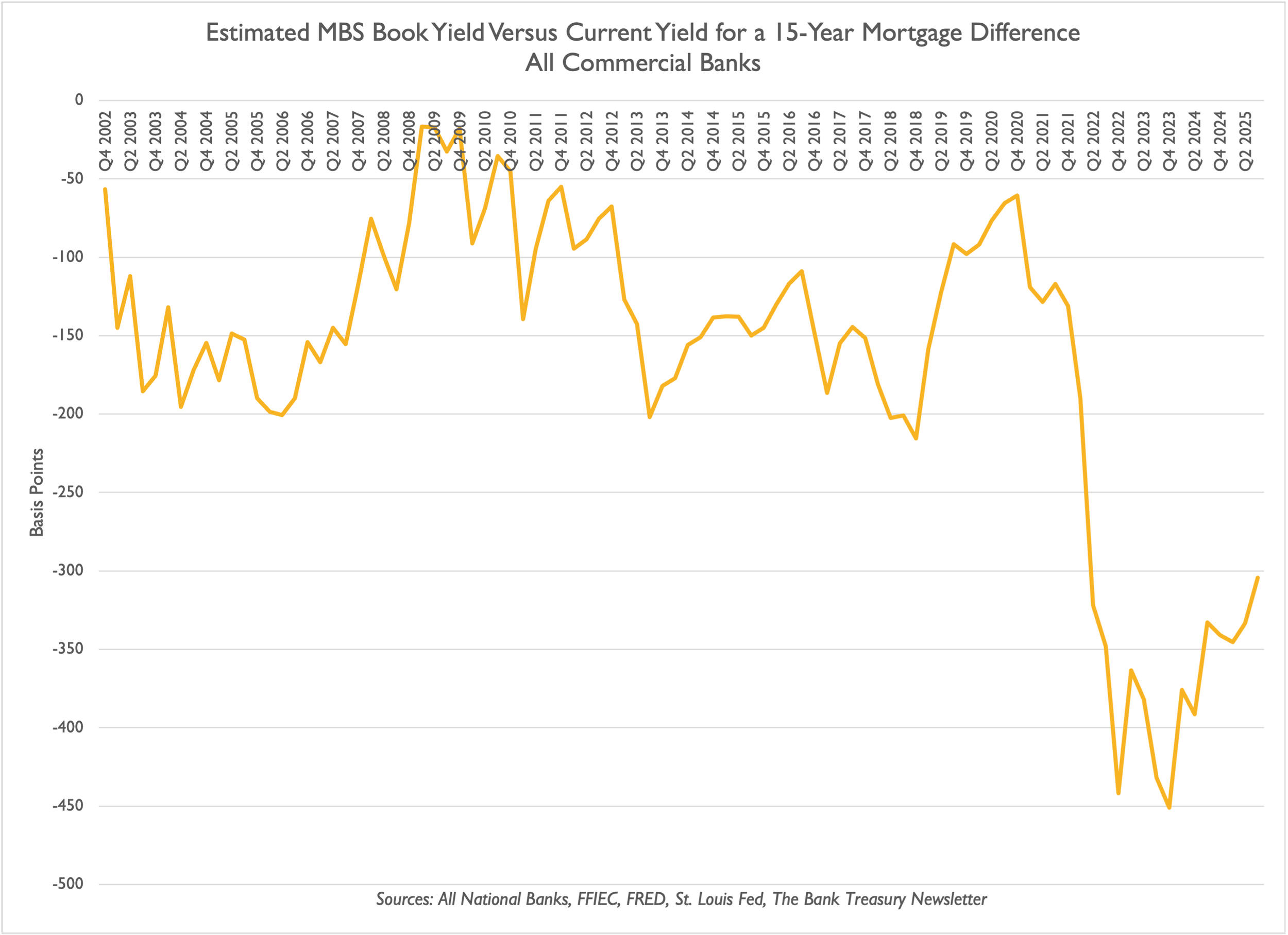

Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac plan to buy up to $200 billion of outstanding Agency MBS this year to bring down 15- and 30-year mortgage rates, which currently stand at 5.6% and 6.0%, respectively. While large banks (H.8 definition) are ramping up purchases of Treasurys (Slide 2), small banks have been buying Agency MBS (Slide 3). Their book yield on their MBS portfolio remains well below the current coupons issued by the Agencies. The difference between a current coupon and the book yield in their portfolios is still 3 points (Slide 4).

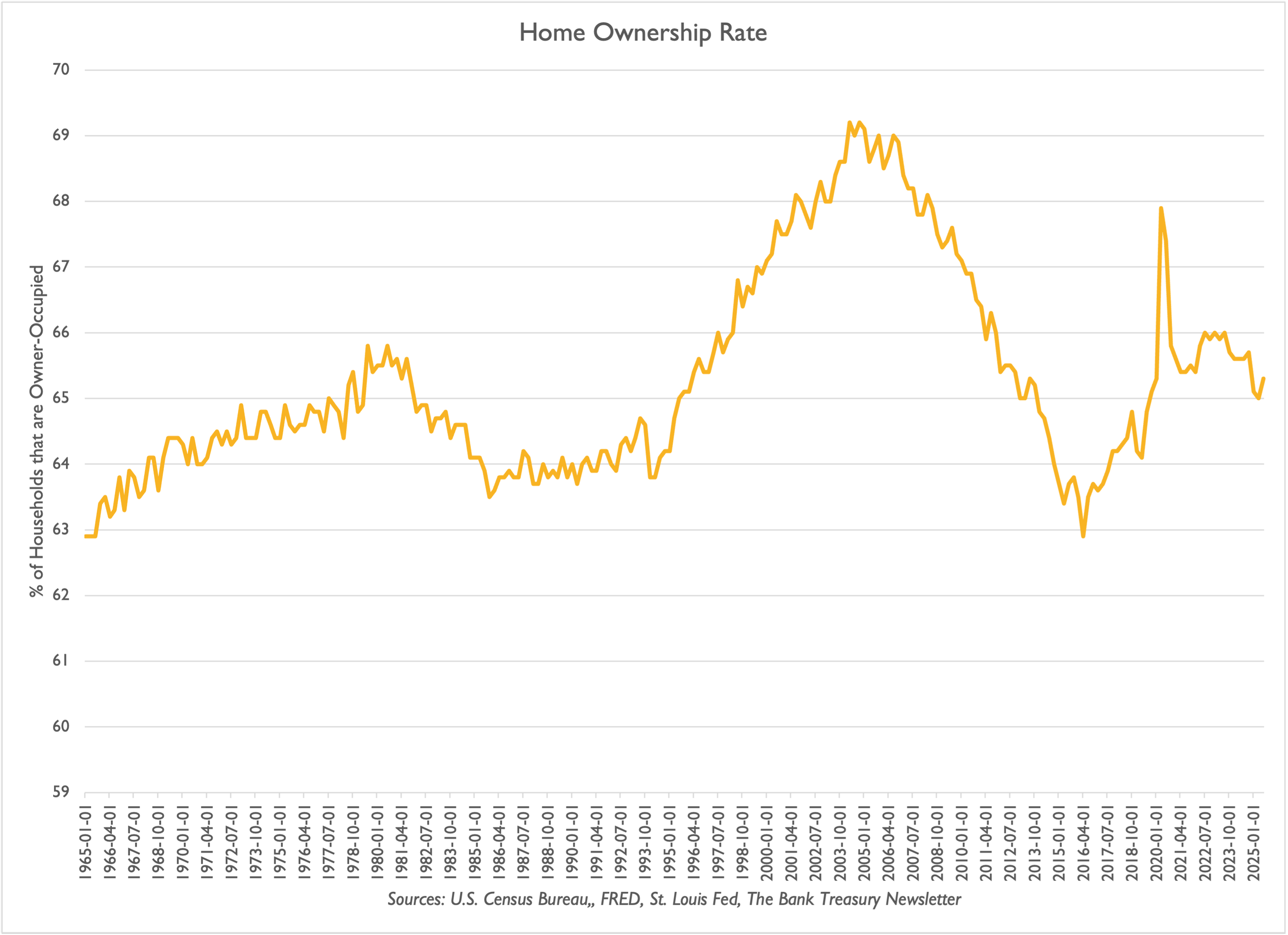

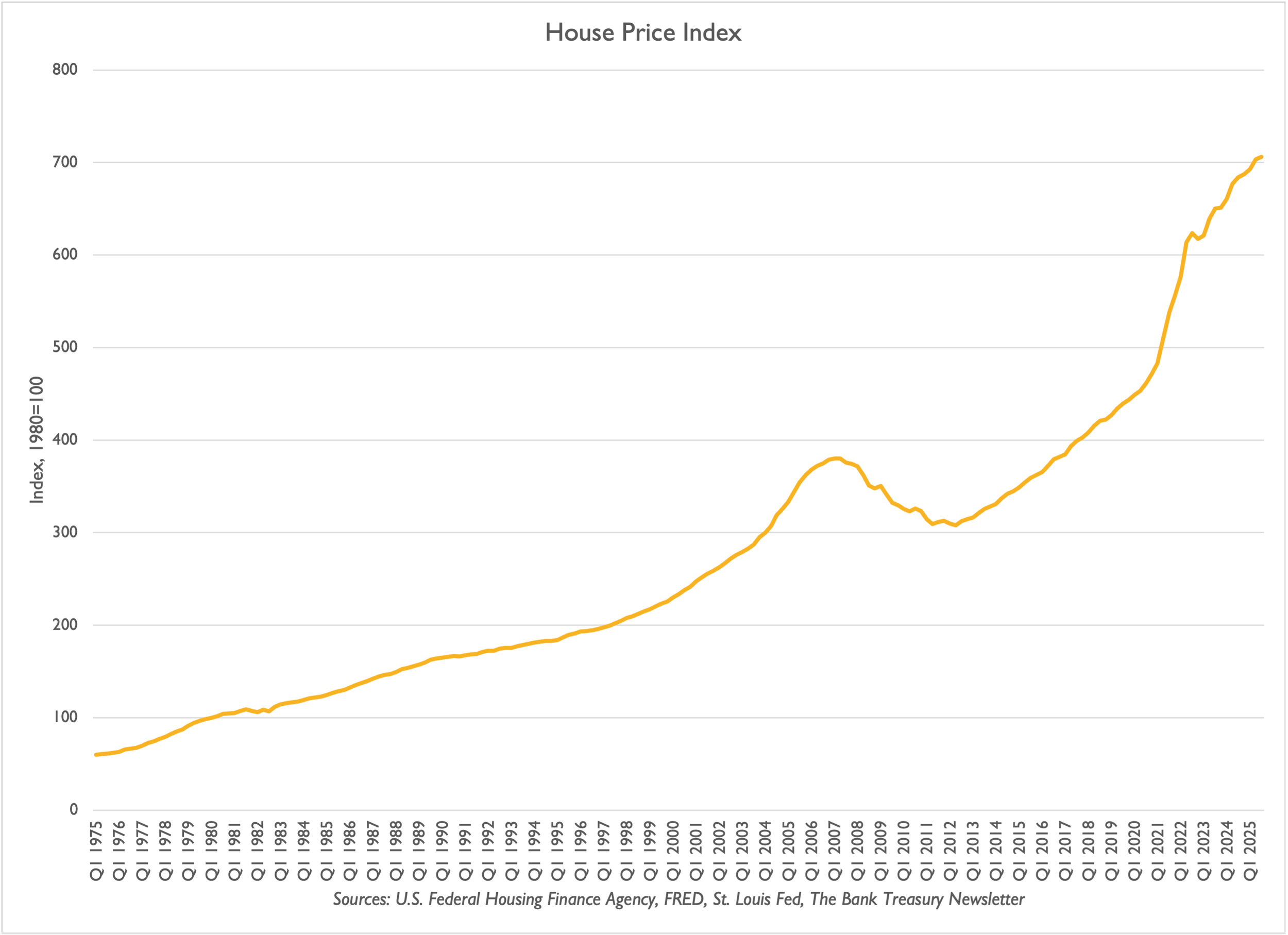

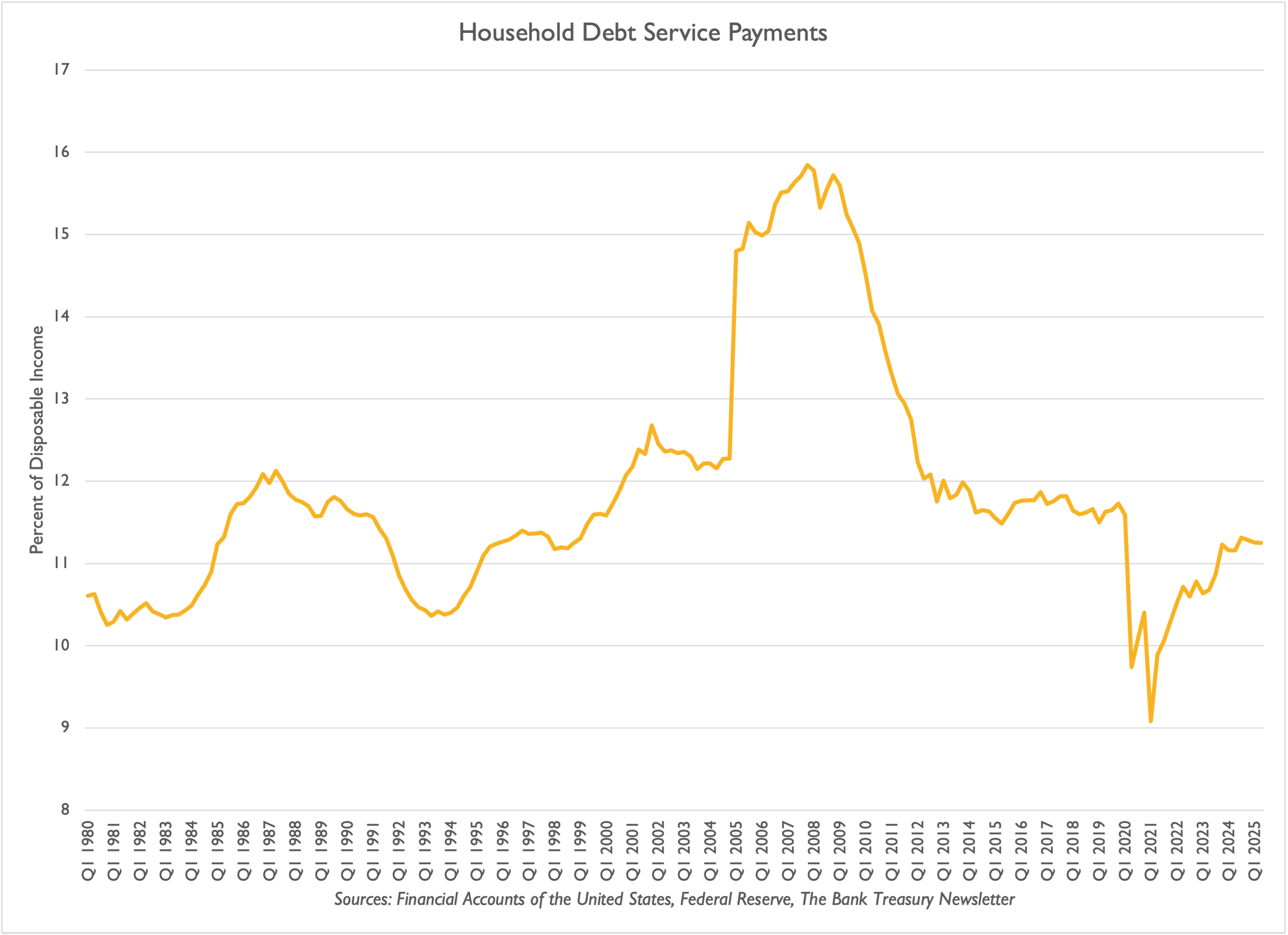

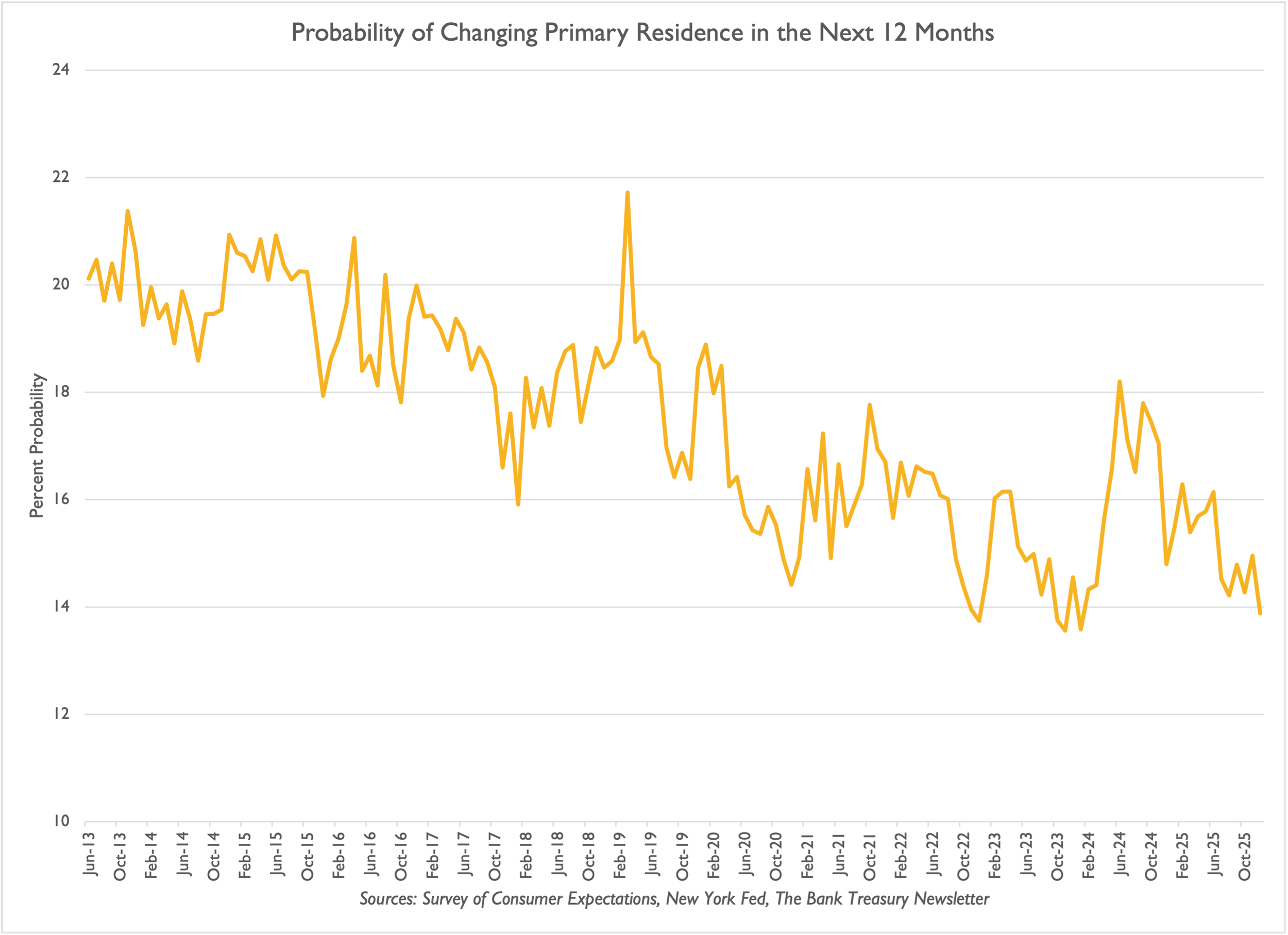

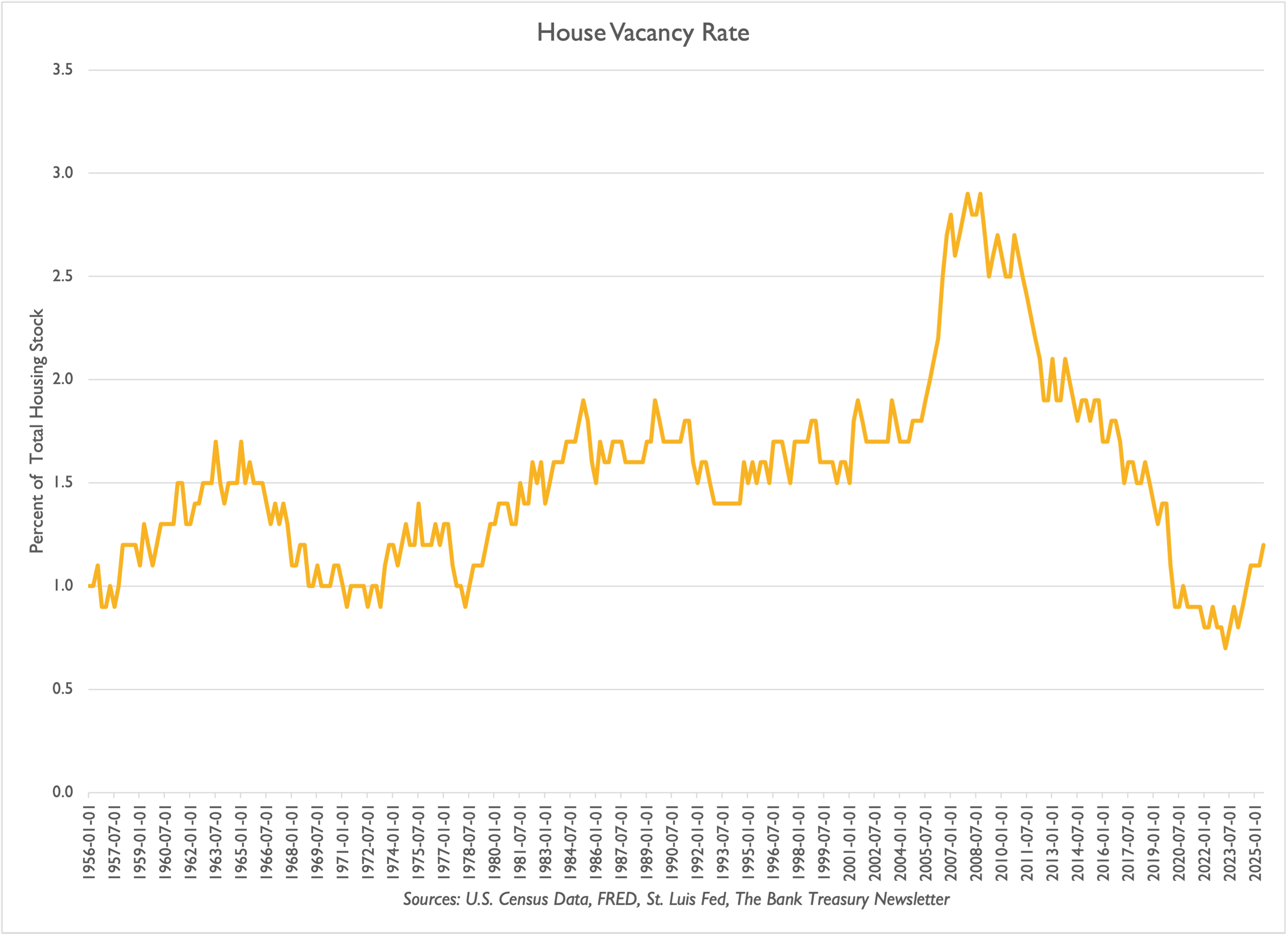

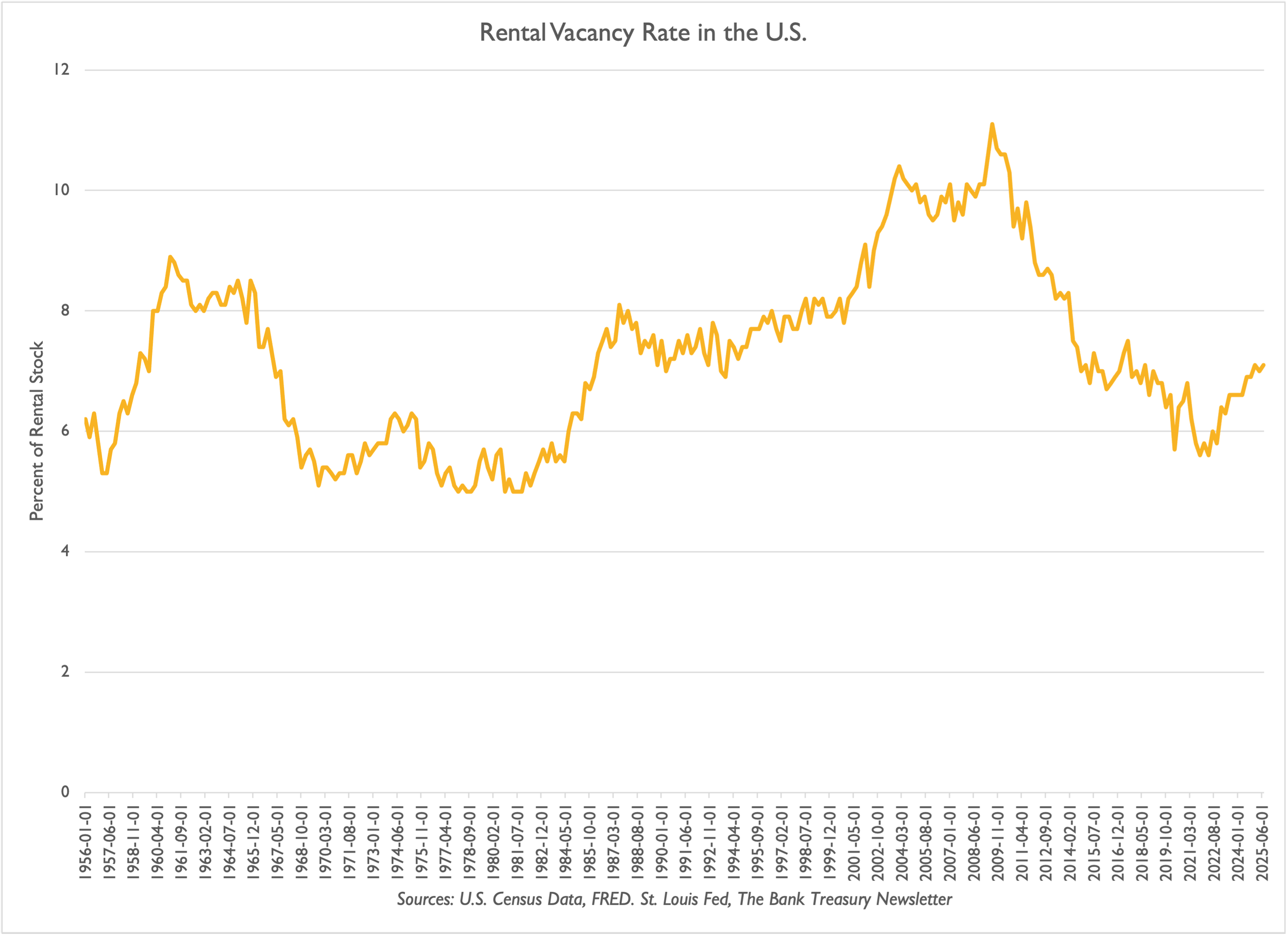

Fundamentally, the public’s demand for mortgage loans reflects a stagnating home-ownership trend (Slide 5), driven by soaring home prices (Slide 6). Sellers may also be less motivated than they have been, because paying a pandemic-era rate on their loans, they can afford to stay in their homes (Slide 7). They are also less likely to move than they have in years (Slide 8). Priced out of the market, the lack of first-time homebuyers is also contributing to the longer time it takes to sell a home (Slide 9) or even to rent an apartment (Slide 10).

Regulators Want To Lower The CBLR To 8%

Large Banks Are Buying Treasurys…

…While Small Banks Are Adding Agency MBS

Bond Portfolio Book Yields Are Still Underwater

Home Ownership Trends Are Stagnating

Home Prices Are Still Soaring

Homeowners Can Afford To Pay Their Mortgages

People Are Less Inclined To Move

It Is Taking Longer To Sell A Home

It Is Taking Longer To Rent An Apartment

The Bank Treasury Newsletter is an independent publication that welcomes comments, suggestions, and constructive criticisms from our readers in lieu of payment. Please refer this letter to members of your staff or your peers who would benefit from receiving it, and if you haven’t yet, subscribe here.

Copyright 2026, The Bank Treasury Newsletter, All Rights Reserved.

Ethan M. Heisler, CFA

Editor-in-Chief